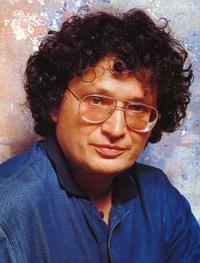

Donald Byrd (Photo Michael Ochs Archive/Getty Images via Billboard)

The jazz world and music community as a whole were saddened by the passing of Dr. Donald Byrd earlier this month. The trumpeter was known as a mainstay of Blue Note’s classic period and for his work in various soul, funk and pop settings. The numerous obituaries and remembrances for Byrd also speak to his role as an influential educator and mentor to many artists.

One of those mentees, Tom Smith, currently serves as professor and Director of Jazz Studies at Ningbo University in China. In the following piece (appearing in English courtesy of the Romanian website Jazz Compass with photos and hyperlinks added by me), Smith provides a heartfelt recollection of Byrd, especially his prescience regarding the global scope of jazz. Smith’s position as an international jazz educator with his “boots on the ground” as well as someone close to Byrd is worthy of several reprints and translations.

Recalling a Mentor

by Tom Smith

This past week, a great and influential jazz musician named “Donald Byrd” died. He was one of my earliest mentors, and as colorful a man as ever known. I first met him in early 1981 following a terrible six-month road gig that began optimistically in Minneapolis before self-destructing in Central Mexico. I was twenty-three and already burned out, having decided a homebound strategy until alternate plans could be discerned and evaluated. Then by accident, I learned of Byrd’s professorship at North Carolina Central [University], and signed on for an ambiguous term of graduate studies, never planning to finish…only to hang and play with the great trumpeter whenever possible.

I met Byrd (the name we all called him) face to face when two days into enrollment, he bolted into my practice room. “I haven’t heard a straight horn tone since I got here,” he said. Then he introduced himself, followed by my cursory, albeit “hamfisted while trying to be cool.” admirer confession. I think that really threw him off, considering a recent unexplained anonymity, perplexing in light of numerous albums and freshly recalled affiliation with a Blackbyrds’ hit called “Walking in Rhythm.” Then, he took me into his office and we jammed for an hour or so. After that I had Byrd pretty much to myself for any amount of arbitrary brain picking, and with him being the big talker that he was, such exercises were a joy to pursue.

I think Byrd saw me as this enigma who was looking for something he couldn’t find. So, within that context, he tolerated our daily banter, while some of my favorite interims included solitary evenings where he passed along Art Blakey gossip, while sharing Frank Zappa recordings. He was especially fond of the Lather set, and outright stole my copy of Studio Tan.

Donald Byrd and Tom Smith (photo courtesy of Tom Smith)

Still, those discussions were never entirely perfect. Truth be known, we fought tooth and nail about any number of things, especially jazz. Back then, I was an unforgiving hard core, which made it easy to sense my loathing for his newer “get some money” approach. Subsequently, he made it abundantly clear that lectures from overreaching kids were beneath his pay grade. In the process, I acquired numerous scars, including his being mad enough to withdraw a prior touring commitment. But that’s the way Byrd was: hot, cold, turn on a dime.

Not surprisingly, he was up on current affairs, while intrigued with Eastern Bloc nations. Byrd was in fact the first musician to tell me about the Romanian curiosity for jazz. He even periodically enlisted diplomats to get him there, an aspiration never realized but always on his radar. His intuitive knowledge of Iron Curtain behaviors always fascinated, and as the years passed those places assumed a greater importance for me. Sometimes, Byrd’s assumptions were downright prophetic.

“Watch what happens when Russia leaves,” he said. “Those people will hook up with the money countries and musicians will get their asses out of there.”

“But what then, Byrd?” I asked. “That’s going to be up to them,” he replied. “But we’ll be deep in the middle of it, you can bet on that. Then later, musicians will return to their cultures, because it’s just too hard to walk away from what you are.” Then he looked me square in the eye and shared another deeply furrowed insight. “The older ones will stay right there, insisting on taking money they will think belonged to them as young men,” a tacit attack on my misdirected indictment of his more human inclinations. After all, I could never in a million years imagine how many different ways Black musicians were robbed in Byrd’s time, any more than I could understand the plight of older Romanians deprived of their own paydays. Still, while most of the past decade unfolded, I diligently fought for contrasting outcomes, while knowing in my heart of hearts that Donald Byrd’s all-encompassing prophecy had indeed come to fruition.

“But what then, Byrd?” I asked. “That’s going to be up to them,” he replied. “But we’ll be deep in the middle of it, you can bet on that. Then later, musicians will return to their cultures, because it’s just too hard to walk away from what you are.” Then he looked me square in the eye and shared another deeply furrowed insight. “The older ones will stay right there, insisting on taking money they will think belonged to them as young men,” a tacit attack on my misdirected indictment of his more human inclinations. After all, I could never in a million years imagine how many different ways Black musicians were robbed in Byrd’s time, any more than I could understand the plight of older Romanians deprived of their own paydays. Still, while most of the past decade unfolded, I diligently fought for contrasting outcomes, while knowing in my heart of hearts that Donald Byrd’s all-encompassing prophecy had indeed come to fruition.

Back in 2004, I wrote a magazine article describing the future exodus of Romanian artists. I called it, “The Reverse Migration,” and was astonished by how some reacted, as if to imply I had manifested something Romanians already knew to be gospel. But nine years ago, with [European Union] ascension just over the horizon, popular wisdom asserted that most, if not all Romanian artists would scurry across Western borders faster than you could say “Ceausescu.” It was further assumed that Romania’s small but massively talented family of jazz musicians would be among those most severely affected, if not irreparably damaged. Romania and Bucharest in particular, was blessed with a good quantity of talented jazz performers, who undertook numerous important tasks, including participation in any number of worthwhile endeavors, while simultaneously creating most of the jazz everyone there took for granted.

Alex Simu with Srdjan Ivanovic’s Quartet at the Dutch Jazz Competition, 2008 (Photo courtesy of Alex Simu)

As a Fulbright Professor at the National University of Music, I had the good fortune of teaching Romania’s best young jazz musicians. But in all candor, I was largely disappointed by their diminished sense of artistic nationalism, and perennially dismayed by their unhealthy infatuation for Western art. “Just show us how to play in your manner,” they would say. “If you want to help, show us how to secure Western residencies,” the hook to any admission that preceded a desire to leave Romania. Then just as Byrd had predicted, a Western migration of young jazz musicians did indeed occur. It started six months into my first residency when a young saxophonist named Alex Simu bolted for Holland. After that, the floodgates opened, and few of my class remained, leaving a handful of persistent loyalists, young works in progress, and a core group of older musicians in their stead, with some harboring no desire but to see all work go into their pockets alone.

Due to unforeseen circumstances, the yang of my theory was proved unfounded. Westerners never came to take those jobs abandoned by emigration, seeing as how there were none to take. A great 2008 recession had seen to that.

Following a brief return in 2009, I was very concerned about Bucharest while harboring guarded optimism for the rest of the country. Timisoara was certainly a bright spot, the result of a failed but legacy successful jazz school that rejuvenated Western Romania’s happily optimistic Banat infrastructure. Then Cluj profited from six months with Dave Brubeck’s oldest son Darius, while old Fulbright loyalist Rick Condit reinforced his efforts in Iasi. Soon, I realized that what remained could most likely survive as a non-stagnant national product, deemphasizing Bucharest to some extent, but in turn holding dear old legacies for as long as required, before Romania’s young prodigal sons (now older, more seasoned men) returned single file through Bucharest’s Arc De Triumph. Still, this essential reshuffling could not deter those enterprising and creative souls, both young and old (such as Mihai Iordache, Raul Kusak, Irina Sarbu, Michael Acker, etc.) who have kept Bucharest’s jazz scene alive despite any number of obstacles.

In the meantime, the Alex Simus, Lucian Bans, Catalin Mileas, Petru Popas, Arthur Baloghs and George Dumitrius continue to expand their expat influences, while growing exponentially as savvy, marketable performers, all quality driven and ethical to a fault.

I have also taken note of the current inclination for Romanians to sing jazz in their own language, not because they have to, but because they want to. This in turn seems intertwined with those Romanian folk melodies I currently hear in the motivic expressions of young performers: musicians who see their jazz not so much in terms of Americanized cloning, but as the melding of a relevant and viable name brand that says “We’re from this place and this is our way.” It’s also nice to hear them share how they’re interested in what Alex, Catalin, Lucian or George are doing even if it isn’t in Romania, because like all great diasporas, jazz culture can most certainly achieve highest enlightenment when on the move.

While reflecting on the teachings of my old mentor Donald Byrd, I can easily imagine his looking down just long enough to shake his head and say “I told you so.”

While reflecting on the teachings of my old mentor Donald Byrd, I can easily imagine his looking down just long enough to shake his head and say “I told you so.”

[Jazz Compass Editor’s Note] From 2002 to 2008, Tom Smith was a six-time Fulbright Professor of Jazz in Bucharest and Timisoara. He is currently a Professor of Music at Ningbo University, in Zhejiang Province, China.