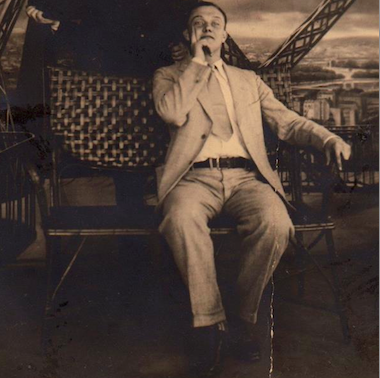

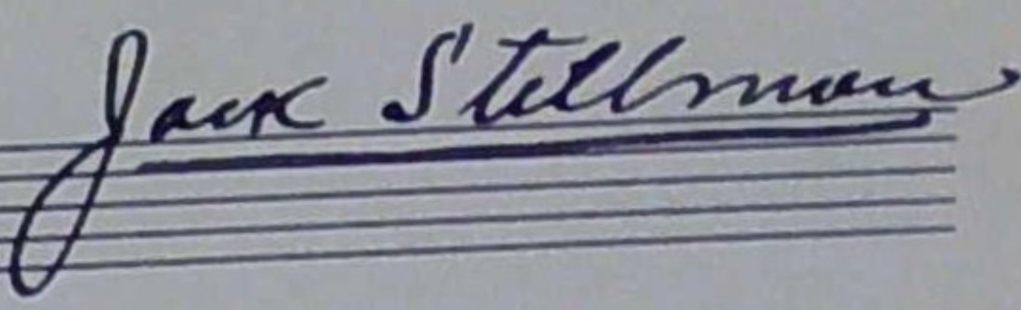

Plenty of records made during the twenties show “Jack Stillman” on the label. Contemporaries praised his abilities as an arranger and trumpeter. Collectors and hot jazz lovers still enjoy his records. Yet he’s far from the most well-recognized musician of the period. Compared to other studio bandleaders, he’s not even one of the period’s most prodigious recording artists. He wasn’t strictly a jazz musician, so history books left him out of their story.

Still, the man made a lot of great music, which is always enough to spark curiosity. Initial research turned up a modest paper trail. Stillman earned little press coverage or advertising. There are no extant interviews or diaries. No one archived his papers (assuming he had any), produced a career retrospective, or made him a dissertation subject.

A lucky Google search led to his great-grandson, whose father lived with Stillman for the first six years of his life. This gentleman heard stories about his great-grandfather and was happy to shed light on his relative’s life outside the studio and beyond the Jazz Age. He and his father shared a love of music as listeners and performers, a love they traced back to Jack.

Stillman’s passion for music resonated through generations of his family. I felt an echo of that pride talking to his great-grandson. He’d never met Stillman, but he loved talking about “the accomplished musician in the family.” That affection inspired me to keep digging and learn more about those accomplishments.

Studio Dance Bands of the Twenties

Jacob “Jack” Stillman is best known for his records as a bandleader. Musicians like Stillman, his partner Nathan Glantz, Sam Lanin, and Ben Selvin constantly recorded for multiple companies throughout the twenties. Before there were “big bands” touring the country to make swing a household commodity, “dance bands” of eight to ten pieces practically slept in the studio recording thousands of fox trots, one-steps, waltzes, novelty numbers, vocal accompaniments, and everything else a music-loving, dance-crazed public demanded.

The “hot dance” numbers—fast-paced, jazz-infused performances taking greater liberties with the tune while showcasing the players—are probably the most familiar to record collectors. They were just one part of the job, but what a job they did!

Some jazz historians have dismissed hot dance records as poor commercial substitutes for jazz or stylistic rest stops on the way to the real thing. Isolating solos is a popular pastime—like picking the marshmallows out of your cereal because your parents told you they’re the nutritious part. Purists may dump the whole bowl.

Hot dance records didn’t generally set out to alter the soundscape of American music or plumb the human soul; they were made to satisfy a market. They often relied on a circle of versatile ace sidemen. These musicians’ superhuman productivity and the often-lighthearted songs they recorded have emboldened some critic-scholars to reject the music as generic, inauthentic, immature, and maybe even a little seedy. Entertainment may please some people, but they seek art, which should transcend things like collecting a paycheck.

Anyone cashing the checks is long gone, and the pitches and rhythms on the records didn’t earn a dime, so it’s now possible to try the (perhaps socially ignorant or culturally unsophisticated) activity of just listening to the music. With some patience, aesthetic imagination, and suspension of temporal prejudice, there’s a lot to savor.

Some Red-Hot Work by Stillman

This brings us back to trumpeter, arranger, and bandleader Jack Stillman. Hot dance records are his most well-known and accessible historical document. There are hundreds of them, but “Nobody Knows What a Red Head Mamma Can Do” is as good an introduction as any (and it certainly was for this writer). It’s not Stillman’s arrangement, but it’s easy to hear why it earned him a track on this compilation: it’s an exemplary piece of hot dance music under his leadership.

The catchy tune remains clear. Variations and embellishments never get in the way of humming along or selling the song. Historian David A. Jasen describes American popular music “before Elvis Presley made a song’s performance more important than its publication.” This was when “a song’s popularity was determined not by the number of records it sold but by the number of copies of sheet music sold.” If the song was king, it’s hard to fault these musicians for sticking to it. Ditto for audiences wanting to hear it.

Yet things stay tuneful (rather than monotonous) because the musicians deploy an array of syncopations varying from subtle anticipations of the beat to stretched and clipped phrases. Listeners used to a behind-the-beat swing feel and polyrhythmic experimentation may call it “stiff” or “jerky” (terms many postwar critics apply too frequently). Yet the clearly delineated ground beat and unrelenting rhythmic tension on top of it got people dancing in ballrooms and living rooms nationwide.

This was music unapologetically made for dancing. It had little use for rhythmic displacement. If you’re not swaying your hips to it, you’re probably tapping your foot. This music literally moved people. It’s reductive to dismiss it as a second-rate attempt at copying “real Jazz.” There was simply another rhythmic sensibility at play. In other words, we’re just hearing a different style of music.

There’s also the fascinating sound of pre-Armstrong musicians in a post-ragtime, proto-Redman/Henderson wind and brass ensemble. The most common format heard on records then was a three-person brass section of two trumpets and trombone; two to three saxophonists doubling clarinet and other reeds; and a four-piece rhythm section. The emphasis was on arrangement and collective improvisation. There are dialogs between homophonic brass and sax sections, a sound that still defines “big band jazz” even for casual fans. But this size band—essentially a sextet plus rhythm section—allows for those techniques and other interactions between different voices in the ensemble.

In just under four minutes, “Nobody Knows…” offers brass and saxes trading melody and background accents; gruff trombone fills and wailing clarinet obbligatos a la New Orleans polyphony; creamy sax sections alternating with plummy tenor lead; and jazzy breaks. The vocal and harmonica choruses add even more variety. Stillman even takes over lead trumpet right before the vocal as Hymie Farberman switches from muted to open horn, adding still another shift in texture. Farberman’s solo is far removed from the chordal extemporization that came to define jazz solos. Instead, it’s an exercise in melodic paraphrase, sticking just close enough to the melody so it stays clear while still making it his own.

There are different musical priorities at work in this music. It’s one thing to make multiple choruses of harmonic deconstruction into a personal expression. But how do you make an eight-bar melody statement yours? At a time when the tune was the thing and perhaps a dozen other bands may have been recording the same one, how do you create a unique sound that fits one side of a 78 while selling the song?

There’s no way to know if these questions were on Stillman’s mind or occupying anyone else in the studio. But it’s no stretch to assume he wanted to produce a well-crafted performance. That’s clear from this record’s quality, ingenuity, and charm and others (including all the stuff beyond the borders of hot territory).

Old World Meets Hot Music

On paper, nearly a century later, Stillman may seem like an unlikely source for dance music about a “mama” who knows how to get down. As his great-grandson informed me, he was a devout orthodox Jew. He may have had more conservative sensibilities than those of the roaring post-Victorian popular culture around him. He enjoyed his peak recording years in his forties—not old, but maybe a little mature for pop music. He was also born in late nineteenth-century Ukraine, far from ragtime and jazz’s geographic and cultural roots.

Of course, Eastern European Jewish immigrants and their descendants had a significant role in American popular music. Scholars continue documenting that group’s influence and challenges and exploring the complex socio-political questions around them. Focusing on the prevalence of studio bandleaders from this community, several of the most prominent studio dance band leaders of the twenties immigrated from Eastern Europe. Ukraine alone produced multiple names that would go on to ubiquity first in American households and then on collectors’ shelves worldwide:

| Bandleader | Birthplace | Year of Birth |

| Emil Coleman | Odessa, Ukraine | 1892 |

| Nathan Glantz | Podolia region, Ukraine | 1878 |

| Harry Raderman | Odessa, Ukraine | 1882 |

| Lou Gold | Łódź, Poland | 1885 |

| Sam Lanin | Russia (location unknown) | 1891 |

| Mike Markels | Kyev, Ukraine | Immigrated 1890 |

| Ben Selvin | Son of Russian immigrants | 1898 |

| Stillman | Berdychiv, Ukraine | 1884 |

Some of these musicians were born abroad but grew up in the United States. Raderman immigrated when he was 11 years old. Lanin was just three. Others, like Stillman, came as adults. Birthplace does not explain every aspect of an individual’s upbringing or creative influences. The complete cultural context and larger connections are a topic of their own. But this common thread between a handful of names who made thousands of popular records is worth noting. It also shows how Stillman’s story encapsulates an entire generation of American musicians while unfolding from a unique vantage point.

Jacob “Jack” Stillman was born in 1884 in Berdychiv, Ukraine. Though Stillman’s naturalization petition shows Kyiv as his birthplace, his great-grandson and several official documents confirm he was born in this smaller city about 120 miles southwest of the Ukrainian capital. Berdychiv was a center of Jewish cultural and religious life. It influenced the birth of the Hasidic sect of Judaism in the seventeenth century. By the turn of the nineteenth century, Jews comprised about 80% of the population. Several renowned Jewish cultural figures (including novelist Joseph Conrad) were born there.

Stillman’s hometown also boasted a thriving musical tradition. Perhaps owing to the large Jewish community and the corresponding number of temples, Berdychiv’s cantors were renowned throughout Ukraine. One of the first choral synagogues in the Russian empire opened there in 1850. Like many other Ukrainian cities, Berdychiv also boasted a rich klezmer scene. It’s unclear how Stillman began his musical training or if he participated in these or similar activities. It’s safe to say he grew up in fertile ground for a musical career. Stillman’s great-grandson recalled hearing he had played in the “czar’s band” or some other state/imperial musical ensemble. Sometime before Stillman left for the United States, he and his family lived in Warsaw, Poland, another thriving Jewish metropolis that probably had ample outlets for gaining experience and making money as a musician.

When Stillman immigrated to the United States in 1913, he listed his official occupation as “musician,” implying he was already working professionally. He and his wife had already started a family: all three of their children were born in Ukraine. Stillman’s family may not have joined him for the 10-day journey on the S.S. President Grant when it set sail from Hamburg, Germany. Claiming just sixty dollars to his name at the time (about $1,900 in 2024) and not included in the ship’s passenger manifest with him, Stillman may have had to send for his wife and children later.

He may have first lived with an uncle on Orchard Street in Manhattan’s Lower East Side. By 1915, the whole family was living together in the same neighborhood at 325 East 13th Street. They were still there when Stillman was naturalized as a U.S. citizen a few days before his birthday in 1921.

Volumes of academic research and personal recollections attest to the significance of the Lower East Side as the “capital of Jewish America at the turn of the twentieth century.” Suffice it to say that, between his residence there and his career in the music industry, Stillman was surrounded by people with similar origins and shared identities. That likely helped him make professional as well as personal connections. At the same time, no group is a monolith, and each individual’s experiences, opportunities, and challenges are their own.

In Stillman’s case—someone practicing Orthodox Judaism in a secular industry— it’s unclear if his position affected how he navigated responsibilities at work or in his community. For example, did observing the sabbath prevent him from taking gigs on Friday or Saturday nights? Would the raucous nightlife associated with the period’s popular music have raised more conservative neighbors’ eyebrows? Stillman was both part of and a unique member of a group of artists that, through their records and radio appearances, would gain national relevance in a country that was often intolerant of their ethnicity and faith. Missing work to observe high holidays would be a disadvantage in an already demanding field.

I’m neither personally nor academically qualified to answer these questions. But they remain fascinating issues. They also allow a more nuanced understanding of the man outside the studio.

A Promising Entry into American Music

How Stillman first got into the studio or when he began recording raises more questions. His musical activities right after he arrived in the U.S. are unclear. There was plenty of work in New York City for a young musician. Live gigs may have led to studio work, either from bandmates recommending him to their studio contacts or bandleaders hiring him for record dates. Stillman’s trumpet might be on any of the records and cylinders made at the time.

He managed to get the spotlight for his earliest confirmed recording. “Jack Stillman, cornet solo” is the only performer listed for “The Sunshine of Your Smile” on Edison 80862, recorded April 27, 1920, at Edison’s Manhattan studios in the Knickerbocker building on 42nd Street and Broadway. Judging by its number of recordings, the British song with lyrics by Leonard Cooke and music by Lilian Ray continued to be popular seven years after its publication. This slow, sentimental, old-world love song must have seemed particularly bittersweet for lovers separated during World War I. The Edison release is one of the few instrumental versions from the time.

Stillman is the featured soloist with a light concert orchestra accompaniment behind him. Listeners have noted the marked vibrato in his tone: a “shaky” sound that would identify him on later hot recordings. One brass player describes Stillman’s style as “operatic, like a lyric soprano.” They also hear roots in the Arban method and similarities with Herbert L. Clarke’s solos. Stillman shapes his notes with “miniature crescendos,” which might be a holdover from vocalists of the pre-modern tradition and their frequent use of portamento and swelling dynamics.

This was the only solo disc issued under Stillman’s name. Maybe his sound didn’t appeal to the infamously critical Thomas Edison. He might have been there just to fill the other side of the record. A blurb on new releases in The Birmingham News of April 25 refers to Stillman’s performance as “a companion number” to “When You and I Were Young, Maggie” by Edna White, billed at the time as “the only woman solo trumpeter in the world.”

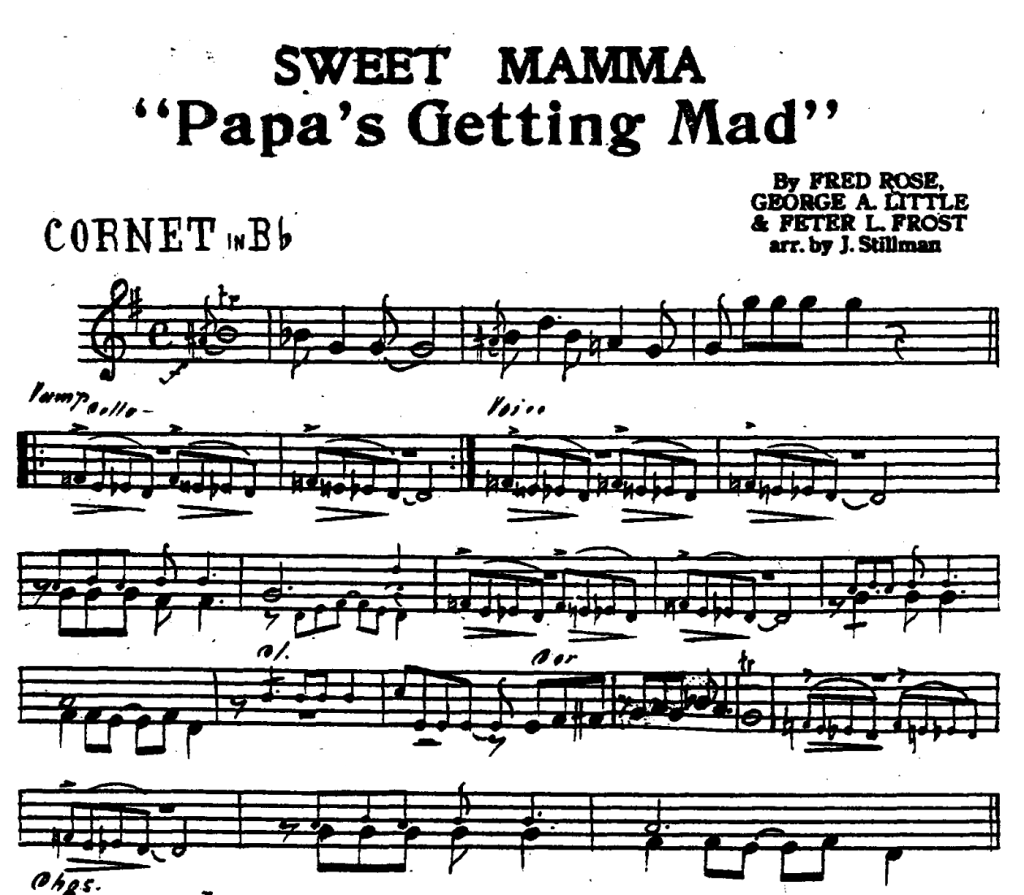

Either way, from that point, Stillman was mainly associated with dance music on record. He had already published several arrangements. His charts from this period ranged from romantic songs like “I Found a Rose in The Devil’s Garden” and waltzes such as “In My Tippy Canoe” to fox trots poised for hot treatment like “Daddy O’Mine” and “Sweet Mama, Papa’s Getting Mad.” Stillman also arranged novelties with humorous titles ( “”) and exotic-sounding tunes (e.g., “Silver Sands Of Love” and “Cairo Moon”). Several of these compositions were written and published by Fred Fisher, whose numerous song credits include the record-breaking “Dardanella” and still popular “Chicago.” The Tin Pan Alley mover would have been a useful connection early in Stillman’s career.

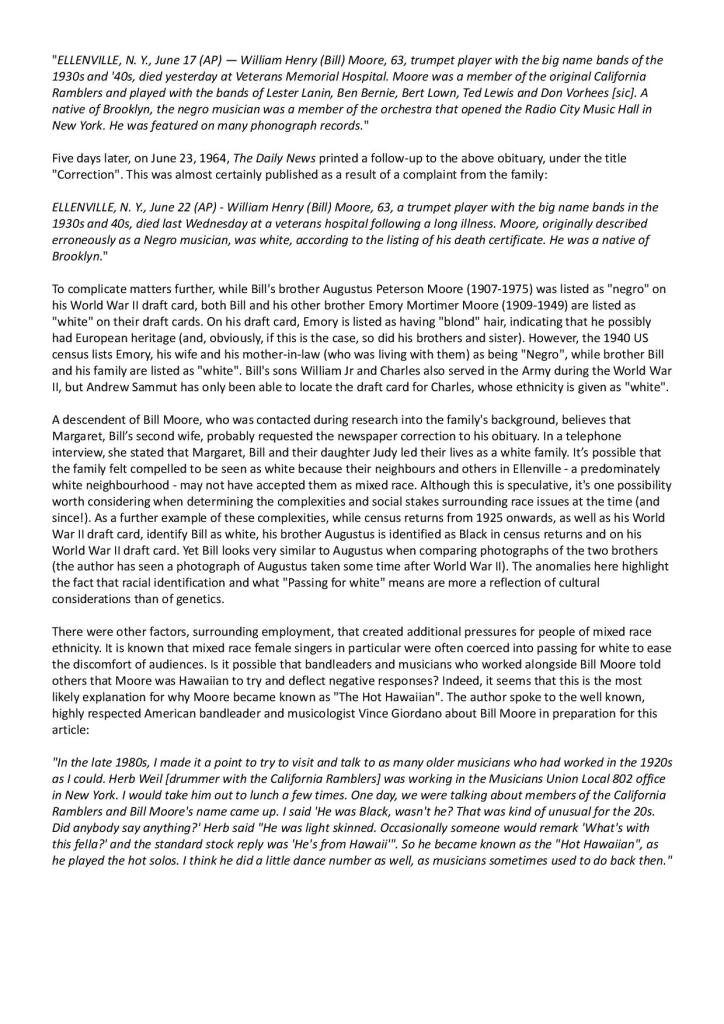

Stillman first appears in discographies around November 1921 with the Club Royal Orchestra under Clyde Doerr’s leadership. As part of Art Hickman’s San Francisco-based band, Doerr and section mate Bert Ralton were instrumental in developing the format and sound of larger dance ensembles using concerted sax sections. After rising to prominence with Hickman, Doerr led the house band at the Club Royal. The job at the swank New York restaurant and a good word from Paul Whiteman (Doerr’s acquaintance from San Francisco) led to signing the band to make records with Victor.

Working in Doerr’s Club Royal Orchestra was probably an instructive experience in writing for and playing with dance bands. The records focus on Doerr’s saxophone, but “All That I Need Is You” from December 1921 offers a good Stillman spotting. The clear, bright lead trumpet with the buzzy tone is a good example of what may have earned him work. Stillman ties together the ensemble without blaring over them. He also projects through the acoustic surface of the record. Discussing trumpeters of the time, historian and musician Andrew Homzy lists “good intonation, consistency, and endurance [as] qualities very much in demand when trumpeters played in clubs and dance halls for hours end-to-end, night-after-night, and were then expected to play perfectly for a recording session the next morning.”

The Hebrew Standard of October 20, 1922, reported him “rendering” musical selections at a party at the Institutional Synagogue on the west side. This may have been a one-off job, but Stillman may have provided similar entertainment at other venues.

He seems to have left Doerr by the middle of 1922. Working with Bob Haring throughout 1923 was likely another enlightening gig. Haring was already one of the most in-demand arrangers of the twenties. In addition to producing hundreds of orchestrations in several styles, he would eventually become music director for Cameo Records—a prodigious and now beloved source of “dime store dance” records. Metronome even gave him a regular column to provide guidance on arranging. Stillman must have learned a few things from their “modern orchestra specialist.”

In addition to these sides, Stillman subbed on a pair of sides with New Jersey-based bandleader Paul Victorin for his Edison session in June 1923. He delivers another clear, firm lead with a noticeable shake at phrase endings. On “Louisville Lou,” we hear his take on low-down “dirty” tone effects. It’s more a flutter than a growl, but it adds color and personality beyond just reading the chart. He stretches out even more on the last chorus of “Carolina Mammy,” propelling the ensemble while varying the theme and preserving the pulse and the tune. If these variations were written into the arrangement, he made them his own

Stillman’s straight eighth notes, arpeggiated fills, crisp phrasing, and tense rhythmic feel show obvious ragtime influences. Historians sometimes reduce the “rag-a-jazz” of Stillman and similar players to a transitional style or write it off as “old-fashioned.” There’s a tendency to treat jazz history as a fast-moving vehicle: musicians were either hip enough to ride or got left behind. Progress may help organize narratives, but the concept doesn’t necessarily reflect the reality of working musicians.

About a month before Stillman and Victorin recorded together, King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band with young Louis Armstrong waxed their first records. Those musicians and their fellow New Orleanians living in Chicago were already having a huge impact on the continuum of regional styles and musical idioms that would be defined as “jazz.” The formation of jazz into a distinct art form is another rich topic far beyond this article or writer. Louis Armstrong’s influence alone is worth endless appreciation. Suffice it to say that, in subsequent histories, that music would supplant anything else previously called “jazz.”

Yet Stillman arrived in the United States in 1913. He witnessed ragtime’s heyday and its decline. He was probably still playing ragtime or ragtime-influenced repertoire even as the blues craze was in full effect during the early twenties. It’s safe to say that Stillman and other musicians of the time were exposed to a wide range of music. They synthesized nascent jazz and blues alongside other genres in their professional portfolio on top of other musical foundations. But they didn’t necessarily discard what they already heard. A century later, Stillman may not sound like what we expect from a “jazz trumpeter.” Disliking how a Ukrainian immigrant in New York during the twenties plays the trumpet is a matter of taste, which everyone is entitled to. Yet expecting them to sound like a New Orleans transplant working in Chicago is unfair.

Discographer and musician Javier Soria Laso (who compiled a definitive Jack Stillman discography alongside this article) points out that Stillman joined trombonist Harry Raderman’s group as trumpeter and staff arranger by late 1923. He stayed with the trombonist and bandleader through November of the following year.

Odessa-born Raderman was active in the thriving New York Yiddish music scene before becoming popular through his “laughing trombone” and work with Ted Lewis. His recordings as a bandleader include fascinating examples of different musical influences cross-pollinating. As just one example, musicologist Henry Sapoznik points out “Song of Omar” with Raderman playing the doina—“the DNA of Yiddish music”—in a duet with clarinetist Pinchas Glantz (a relative of Stillman’s future partner).

Stillman’s arrangements for Raderman feature novel ensemble touches that don’t seem part of the publishers’ stock arrangements, such as the brass and saxes in humorous stuttering dialogs on “Ev’rything You Do.” “Louise,” from the same session, shows off warm reed textures. Ascending chromatic figures add momentum and texture to “Mandy, Make Up Your Mind.” That arrangement also integrates Raderman’s signature trombone sound as a lead voice and in background riffs, while“ Driftwood” assigns the laughing lines to the saxes alongside cascading phrases answering the vocalist. These may have been “special” arrangements for the Raderman band or examples of Stillman doctoring arrangements with new ideas. Either way, they sound like the work of a skilled arranger who knew how to tailor music for the band.

With Raderman, Stillman also began showing his knack for arranging waltzes. Waltzes are sometimes a tough sell for jazz-focused collectors and listeners, but audiences at this time enjoyed a varied musical diet. Benny Goodman recalled older couples requesting waltzes well into the swing era. Like any other musical genre, if we don’t expect them to “do” the same things as jazz records, dance band waltzes reveal interesting musical ideas.

Stillman’s charts for Raderman capitalize on the contrast of Larry Abbott’s golden soprano sax wrapping countermelodies and obbligatos around Raderman’s gruff trombone. “Kiss Me Goodnight” plays wah-wah brass effects against the more straight-laced waltz. The side also features a floating, broad-toned “hotel band” tenor in the lead, a simple but effective voice that comes up in both fast numbers and waltzes arranged by Stillman. It sounds like he really enjoyed the sound of tenor sax with a clarinet or soprano sax providing harmonies and counterpoint above it.

Work with Raderman must have benefitted Stillman in several ways. Recording with a popular bandleader probably paid well. It likely also provided valuable experience as an arranger and a trumpeter. Raderman might have shown Stillman how to organize and direct record sessions. At the same time, most of these sides were made for Edison, allowing him to make further inroads with the label. Raderman likely introduced Stillman to his cousin, saxophonist Nathan Glantz. Glantz and Stillman became close musical partners, frequently playing on each other’s sides with the same circle of studio musicians, using Stillman’s arrangements.

Hot Dance, Stillman Style

Jack Stillman’s first record session under his name took place on November 25, 1924, for Edison. He kicked off his long career as a studio bandleader with a pair of exemplary hot dance sides.

Hymie Farberman’s snappy lead trumpet boots both pop tunes into hot territory. Helen Clark and Joseph Philips’s vocal duet on “To-morrow’s Another Day” may have been lifted straight from the revue Artists and Models of 1924, but the rest of the arrangement sounds like it was made for this session; it’s unlikely the pit band banjoist went this hard or the instrumental soloists got this much space on Broadway.

“That’s My Girl” is just as melodic and danceable. Its stop-time banjo chorus bursts into a wild collective improvisation before Arthur Hall’s vocal.

Somehow, it all fits together. The jazzier elements of the record sound less like subterfuge and more like an exchange of approaches to the source material. This is an eight-minute musical variety show for people spending their hard-earned money on a record.

Stillman and his family had moved to Brooklyn at some point before 1925. Jack and Lena would stay in their home on 54th Street off 11th Avenue for the rest of their lives. The Borough Park neighborhood already included a large population of Orthodox Jews (and is now home to the largest Hasidic community in the United States). Music kept Stillman busy, but he and Lena still found time to volunteer at their synagogue frequently.

By the mid-twenties, Stillman was leading, arranging, and playing trumpet for his recording bands, on Glantz’s sessions, and with other groups. Abel Green’s record reviews column for Variety of March 1926 mentions Stillman as one of the “staple recording orchestras” in the business. Just a year earlier, in the same column, he was a “new Edison recorder!”

It’s unknown how many professional commitments Stillman had outside the studio. Stillman’s daughter told his great-grandson that Jack led a band in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, “where he also recorded,” suggesting he had a regular gigging band. But the timeline is uncertain. The only record of a live performance from this time is the Jewish Daily News reporting Stillman’s band providing music for a dance hosted by Young Judea of New York at the Waldorf Astoria in October 1926.

As the discography shows, Stillman didn’t record daily, but he came close—and was often waxing sides for more than one label in a day! A survey of Stillman’s prodigious recorded output is beyond the scope of this article. It would require a book of its own. Yet a few sounds and individuals stand out—starting with his trumpet.

By the mid-twenties, Louis Armstrong was introducing a virtuosic approach to jazz trumpet while revolutionizing American popular music’s concept of rhythm. But Stillman’s seemingly unflashy style has its own merits. His prominent vibrato and bright tone are distinct even through century-old, acoustically recorded surfaces.

“Charleston of the Evening” reveals a strong, confident lead. Phrases throb over the ensemble. A slight but deliciously nasal edge to his sound adds intensity and color. Tweedle-Dee, Tweedle-Doo with pianist-arranger Bill Perry shows off Stillman’s ringing middle register in a small group setting. It’s also an excellent example of how New York-based combos approached the New Orleans small group style. Stillman’s clipped attack dials up the intensity of records like “I’d Rather Be the Girl in Your Arms.” Critics sometimes pan the staccato articulation of pre-Armstrong players as a holdover from military bands. But it’s as valid as any influence and adds a distinctly tense feel.

He wasn’t the only bandleader of the period to perform on records. He was clearly more than just competent. Yet there’s less of Stillman’s trumpet on record as the twenties progressed. Other players got most of the audible space on record, with a few names popping up regularly in the studio with Stillman and his co-director Nathan Glantz. Their technical skill and ability to turn out performance after performance in various styles—as hot or sweet as the music demanded—with polish and efficiency is impressive. But each was a unique stylist.

Trumpeter Earle Oliver’s big steely sound, slashing articulation, and distinct growl are an intriguing foil for Hymie Farberman’s approach. Listen to Oliver’s zig-zagging paraphrase of “Dreaming of a Castle in the Air” or how he shreds through the funny little ditty “The King Isn’t King Anymore.” Compare it with Farberman’s crisp attack and subtler sense of syncopation. When Stillman shares lead or solo responsibilities with other trumpeters on the same side—like Farberman for “Nobody Knows What a Red Head Mamma Can Do” or alongside Andy Bossen’s careening lines on “I’m Knee Deep in Daisies” with Charlie Fry—it adds even more color and contrast.

Larry Abbott’s reed doubling and hours in the studio were Herculean even by the period’s high standards. He displayed golden tone and mellifluous phrasing across soprano, alto, and tenor saxophones (for example, respectively, on “Louise,” “Italian Rose,” and “I Found A Way To Love You). But he could turn just as hot on any horn. His tumbling clarinet obbligatos enlivened perhaps hundreds of collective ensembles, and he made the bass clarinet a compelling solo instrument.

Nickname aside, reedman Ken “Goof” Moyer was a solid hot player, even with obvious novelty touches. His cavernous, burbling baritone saxophone is instantly recognizable—for example, following his clarinet outburst on the Stillman original “Come On and Do Your Red Hot Business” or floating into his lead on “I’d Rather Be the Girl in Your Arms.”

Banjoist Harry Reser was a bona fide virtuoso playing with a rocksteady beat and an array of string textures. He could become a rhythm section unto himself: listen to the percussive strokes and cross accents on “I Want You Back Old Pal.” John Cali was Stillman and Glantz’s other preferred banjoist, adding his light but propulsive roll and strum. Banjoists like these exemplify why musicians wanted that instrument in their rhythm section (beyond practical considerations of acoustics and recording technology).

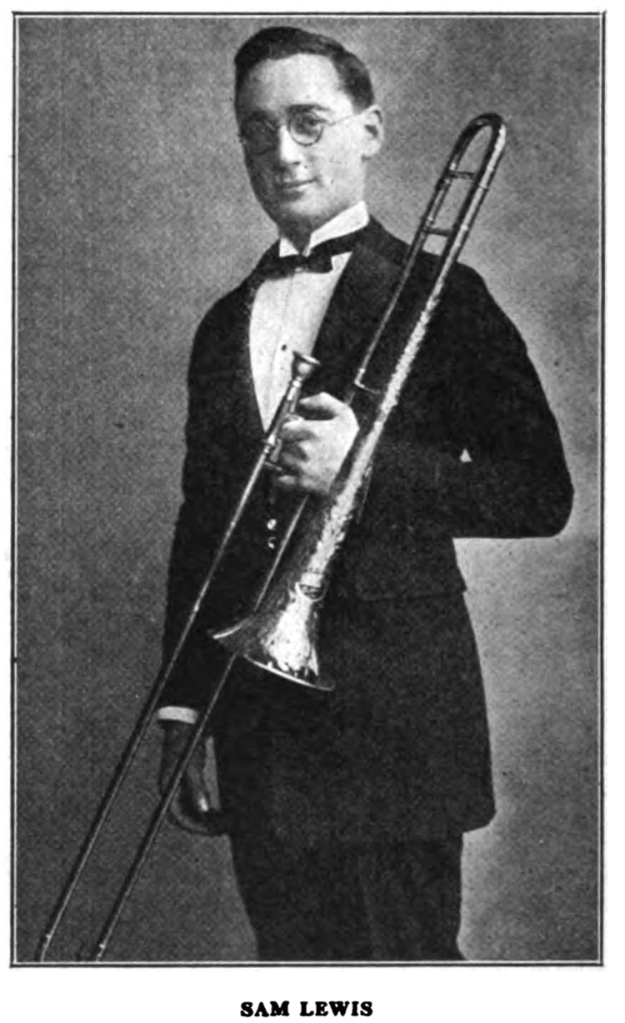

Trombonists Ephriam Hannaford and Sammy Lewis had the disadvantage of being born outside New Orleans and playing at the same time as Miff Mole. They’re virtually forgotten outside of twenties music aficionados. So much for the verdict of posterity! Lewis’s blustery paraphrases and well-timed fills between the top voices show a gifted ensemble player, like on “By the Light of the Stars” or “Show Me the Way to Go Home.” Ten years Lewis’s senior, Hannaford plays with a more ragtime-influenced rhythmic sense, for example, in his lines under the ensemble on “Alabamy Bound.” His darker sound also gives an august feel to straight melody statements like those on Gennett’s instrumental version of “I’m in Love with You.”

Several other musicians were often in the studio with Stillman, but Nathan Glantz appeared on more records with him than anyone. He frequently played multiple instruments on the same side, including all the standard saxophones, clarinet, and bass clarinet plus flute on occasion and even oboe. A hundred years later, it’s easy to pick out Glantz’s ripe, bright, vibrato-laden saxophone. History has not been kind to his distinct sound. If he even gets mentioned, it’s often as a joke, and the speaker is usually laughing at—not with—Glantz. When I mention enjoying Glantz’s playing, responses range from incredulity to disgust (like telling someone you savor a good olive loaf).

There’s no point arguing taste, but it shouldn’t be a factor in historical analysis. The fact is that Glantz gives a fascinating peak into the intersection of ragtime, jazz, show music, light classical and parlor repertoire, possible conservatory training, klezmer, and everything else a Russian immigrant born over twenty years before the turn of the century who lived and performed in New York City might have been exposed to. Nearly a century later, we can dismiss him as a poor facsimile of an art form just beginning to crystallize around him. Or we can try to hear a whole other musical artifact, neither able to nor interested in sounding like the names now chiseled onto anthologies and syllabi.

Despite appearing together on many records, not much is known about Stillman and Glantz’s professional relationship. They might have met through Glantz’s cousin, Harry Raderman. The details of their partnership—who booked which sessions for what labels, whether they worked on arrangements in the studio or beforehand, what happened to the thousands of pages of sheet music that crossed their stands—are now lost to history. Glantz received much more press coverage than Stillman, but it rarely mentions Stillman.

Billboard magazine of February 1926 sheds some light on their partnership:

“Comedy recorders split: A lot of the lads who record are mourning the split of a famous team: Jack Stillman, the trumpet-arranger, and Nathan Glantz, he of the laughing saxophone. The ‘boys,’ often referred to as the ‘Weber and Fields of the recording laboratories,’ decided to steer clear of each other after an altercation in one of the cutting rooms recently. They provided many laughs for musicians on the date with them, and the boys are hoping they’ll patch up their differences real soon.”

Besides their position as major employers, the report describes Stillman and Glantz maintaining a pleasant atmosphere in the studio. That’s not an easy task in session after session, take after take. Their split may have only temporarily troubled studio players. Judging by the sound of the records, Stillman and Glantz seem to have quickly patched things up and gotten back to work.

Above all, these musicians were ensemble players. Solos were an extension of the group (not the centerpiece of the performance). The different permutations of personnel led to spirited playing and intriguing sounds. These records belie the image of faceless studio drones operating a musical assembly line or creative artists straitjacketed by written music. In fact, the records range from charming to lush to wild. They’re always melodic and rhythmic in their own fashion.

There are too many ear-catching touches to catalog here, but here are a few (personal) highlights from Stillman’s dance band discography:

- Hot brass introduction to and register shifts between sections on “Zulu Sue”

- The Don Redman-like clarinet trio in “A Little Bungalow”

- “Hello, Aloha” with Moyer’s Hawaiian guitar effect on soprano sax followed by Stillman’s powerful lead and Moyer’s hot bass clarinet

- Writing for soprano sax duo behind the vocal on “When You Do What You Do”

- Farberman’s raspy tone and Glantz’s dirty clarinet imparting society band bluesiness on “I Ain’t Got Nobody To Love”

- Saxes leading a stop-time chorus in Charleston rhythm on “One Smile”

- Soprano sax and violin adding an ethereal sound, which also shows off the ensemble’s balance and dynamics, on the waltz “Silver Moon”

In addition to writing his own arrangements, Stillman often revised music publishers’ stock arrangements and added new material. “Doctoring” stocks could set the band apart, while others stuck to the often straightforward published chart.

Musicologist Jeffrey Magee lists instrumental substitution, adding sections for soloists, and rhythmic variation as some “typical doctoring techniques” used by arrangers. Stillman used these techniques while also writing new introductions, codas, and modulatory passages. He also skillfully moved around sections of the stock arrangement for greater impact. Stillman’s care for his work and ear for showcasing the band are on display in touches like bumping up Arthur Lange’s final chorus on “Paddlin’ Madelin’ Home” to the middle of the chart, making room for Earle Oliver’s hot trumpet for the conclusion.

In addition to his prodigious arranging, Stillman also composed several original tunes. Perry Armagnac (in “An Introduction to the Perfect Dance Series and Race Series Catalog” from Record Research 51/52 of June 1963) singles out Stillman’s compositional output on Pathé and Perfect:

“This Perfect catalog includes a considerable number of tunes (many of them quite listenable) not to be found on any other company’s labels. Often the composer credits of these unfamiliar tunes reveal them to be ‘originals’ by members of the band that made the recordings. The largest single contributor in this class may have been Jack Stillman with D. Onivas [an alias for Domenico Savino] a possible runner-up.”

Many tunes weren’t copyrighted, suggesting they may have been written specifically for the record date. Sometimes, the composer is listed as “Tronson” or “Fronson.” Stillman was equally gifted writing peppy but sweet pop songs like “Give Me Your Heart” and “Rainy Day” as well as catchy dance numbers like “Charleston of the Evening.”

The labyrinth of labels, record companies, band aliases, matrices, control numbers, and other data can be another obstacle to decoding the world of twenties hot dance music. However, public demand for dance music and a recording industry that didn’t demand exclusivity from artists meant musicians like Stillman were heard in homes nationwide—even if residents didn’t always know who was creating the music.

It also means modern listeners can appreciate multiple performances from the Jack Stillman songbook. In some cases, there are different arrangements with varying alterations between recordings. Other records offer slight but effective differences, such as the unique sound of hot sleigh bells on Gennett’s “Cooler Hot” or the slightly faster version of “Any Blues” on Oriole swapping clarinet for Reserphone in the last bridge. Multi-instrumentalist, bandleader, and historian Colin Hancock’s compilation of Jack Stillman’s Red Hot Recording Bands features many Stillman originals, and it’s an ideal playlist for appreciating Stillman’s talents.

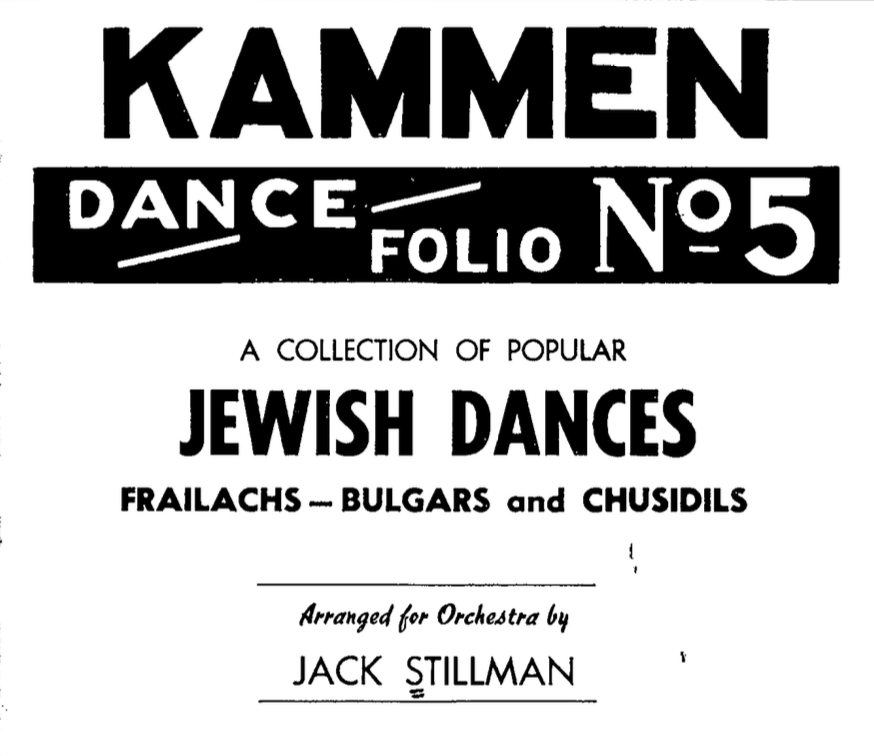

Versatility was crucial in Stillman’s business. In addition to leading and arranging for dance bands, he worked in multiple genres, including folk and Yiddish stage music (which he may have had some personal connection to). In 1928, the Kammen brothers sheet music firm published Stillman’s folio of Jewish dance arrangements. He also arranged a collection of themes by comic actor Ludwig Satz. There are likely other examples of Stillman’s work in this area awaiting discovery.

In Film and Theater

According to Henry Levine, Stillman concentrated on arranging by the end of the twenties. An advertisement for a show at the RKO Theatre on October 3, 1930, includes his name. It’s one of the few printed mentions of him at a live performance. Red McKenzie’s Mound City Blue Blowers shared the bill, but Stillman was likely conducting the orchestra accompanying dancer Ann Pennington.

By the next decade, Stillman may have sought other musical opportunities for his talents. With the Great Depression in full force, he might have wanted an additional source of income. Motion pictures would have satisfied both goals. He’d been involved in film music as far back as 1926 when he arranged “Tramp! Tramp! Tramp!” for a cartoon of the same name from pioneer animator Max Fleischer. Film preservationist Ken Regez notes that this synchronized sound short predates Walt Disney’s “Steamboat Willie” by two years. Stillman also conducted the Harold Veo orchestra as it played for viewers to “ follow the bouncing ball” and sing along with the pro-Union Civil War anthem. He also turns up as an assistant director and organist (!) for the 1929 Columbia Krazy Kat short “Slow Beau.”

Stillman may have contributed to other animated shorts. When queried, a Fleischer Studios archivist explained that early cartoons rarely included detailed credits and most records from this period are lost. Stillman’s versatility as an arranger, knack for concise peppy instrumentals, and ability to efficiently deliver them while directing bands would have made him a shoo-in for this work. Relatives told Stillman’s great-grandson that Jack also wrote scores for silent live-action films, though the titles are unknown.

Records of his film work start appearing after the introduction of sound in movies. In September 1934, trades began reporting that Stillman was heading the newly founded “Sov-Am [likely a portmanteau of ‘Soviet’ and ‘American’] Film Corporation,” a Manhattan-based production company specializing in Yiddish films. Stillman must have thought this market was promising enough to try the production side of the business. He may have also appreciated another way to entertain his community. Filmmaking turned out to be a short-term venture. Stillman would oversee just two movies with Sov-Am.

Di Yungt fun Ruslund (“The Youth of Russia”) was the only Yiddish talkie released in 1934. It opened at the Clinton Theater, which film critic James Hoberman described as one of the first Manhattan theaters to show Yiddish feature films (and a “run-down, cavernous” venue in “one of the most congested and clamorous areas of the Lower East Side”). Di Yungt fun Ruslund ran for just two weeks with limited showings at other theaters. Stillman was also credited as the film’s music director. He likely arranged and conducted the movie’s 20-minute montage of “traditional prayers, Russian dances, and folk ballads.” The film is now lost.

The following year, Bar Mitsve didn’t fare much better despite featuring Yiddish theater star Boris Thomashefsky in his only onscreen speaking role. Hoberman cited this film as a good example of shund: “an inept mishmash, vulgar display, mass-produced trifle, or sentimental claptrap” (though theater historian Nahma Sandrow described this subgenre as “the first artform to express the distinctively American Yiddish community”). Bar Mitsve lasted just two weeks in U.S. theaters but made it to Poland, where Yiddish talkies were rare. It was still playing two years later. Bar Mitsve featured plenty of diegetic music likely scored and conducted by Stillman.

After leaving Sov-Am, he continued making music for films including Vu iz Mayn Kind (“Where is My Child”) and Di Heylige Shvue (“The Holy Oath”) in 1937 and his former Sov-Am partner Henry Lynn’s Di Kraft Fun (“The Power of Life”) in 1938.

Stillman’s film credits disappear after this point. Maybe he didn’t enjoy the film business or wanted to pursue more lucrative work. The outbreak of World War II would bring the Yiddish film industry to a close just as it began flourishing. It’s possible Stillman saw the writing on the wall.

On the other hand, Yiddish theater was a beloved part of life for Jews in New York City through the middle of the century. Scholar and historian Edna Nahson explains that “Second Avenue became a ‘Yiddish Broadway’ where over 1.5 million first- and second-generation Eastern European Jewish immigrants came to celebrate their culture and to learn about urban life in the city…via cutting-edge dramas, operettas, comedies, musical comedies, and avant-garde political and art theater.”

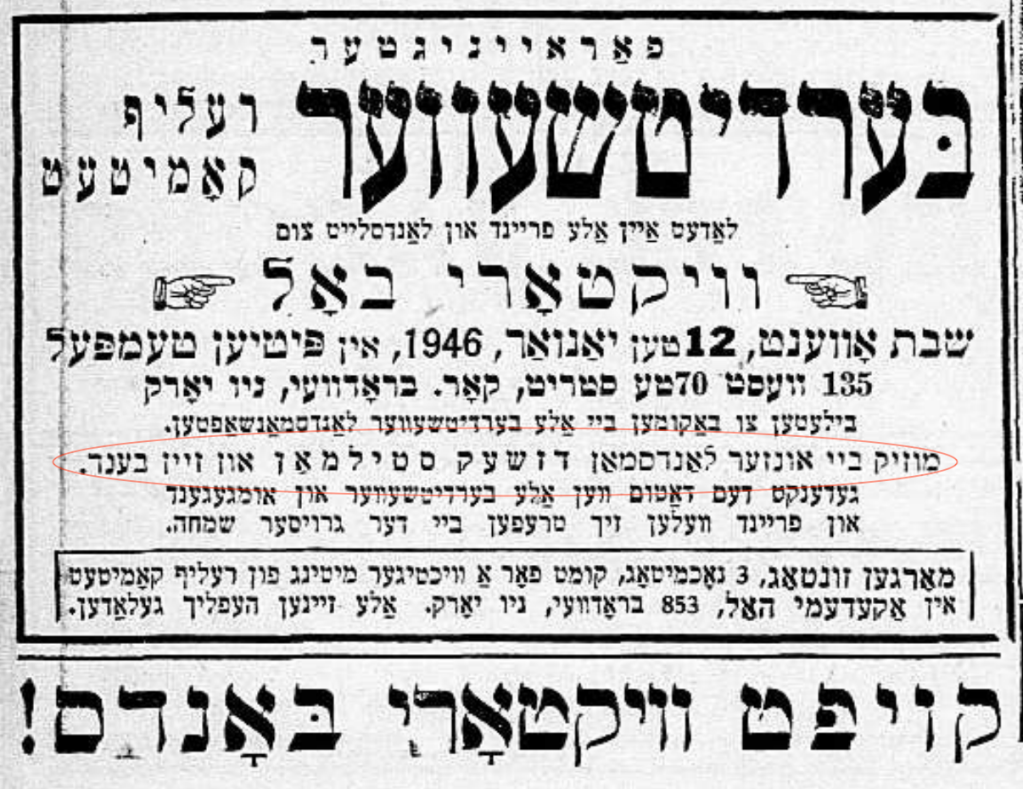

Stillman and his family probably attended shows. He may have worked in some of the theaters. But on May 10, 1940, when the National Theater reopened as “America’s only Yiddish vaudeville house,” “Jack Stillman’s orchestra” was part of the bill. The venue on East Houston Street off of Second Avenue would be his primary gig for the remainder of his life.

Opened by Boris Thomashefsky in 1912, seating roughly 2,000 in its auditorium plus another 1,000 patrons in its rooftop theater, the National Theatre initially focused on dramatic works. Upon reopening, the venue shifted its programming to comedies, musicals, revues, single acts, and Yiddish films. Thomashefsky might have had Stillman in mind after working with him on Bar Mitsve.

Offering entertainment all day, the National must have kept Stillman busy as both musical director and the composer of several shows. His work was popular enough to earn him billing in ads featuring the stage stars booked at the National. Plus, he kept volunteering. Ads for a victory bond fundraiser dance sponsored by the Berdychiv landsmanshaft (social organization) proudly announce “music by our countryman Jack Stillman and his band.”

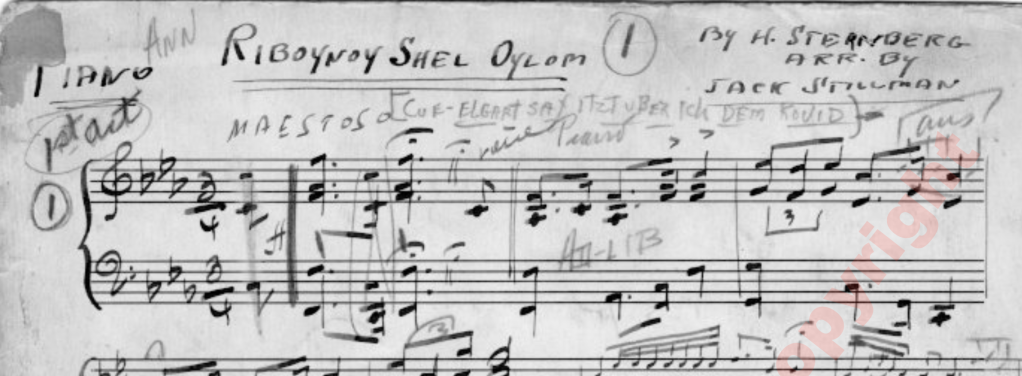

The YIVO Institute for Jewish Research has an extensive archive of records from the Hebrew Actors’ Union. That includes pages from Jack Stillman’s arrangements for the theater from 1945 until his death. Most of the song titles are in Yiddish, and most song folios are incomplete, filled with random parts for various brass, reed, string, and rhythm section instruments. It’s also unclear whether Stillman or a copyist wrote these manuscripts. Yet they’re one of the few original documents left behind by this talented musician.

Stillman’s death certificate reports he died of a heart attack on May 10, 1947, at around 11:00 p.m. in a “theater” at 111 Houston Street. Given his prodigious output, varied career, and evident work ethic, it’s no surprise that he passed away at work in the National.

Stillman’s Story

Jacob and Lena Stillman’s headstone inscriptions say it all: a quill pen with paper and a piano flank a trumpet suspended over a pair of hands holding a baton in front of a musical score. Musician and bandleader (as well as living patron saint of this era’s music) Vince Giordano notes that the music on the score is “Hatikvah,” the national anthem of the Zionist movement at the time and then the state of Israel. This was also the couple’s headstone. Lena may have also been a musician or simply shared her husband’s love of music and pride in his heritage.

People don’t mark their final resting place thoughtlessly. Stillman’s headstone is a monument to how much his music and his faith meant to him. It’s also a reminder of the talent and rich lives behind the discographical data. Stillman’s story spans imperial Russia, Tin Pan Alley, and Yiddish Broadway, among other cultural sites. It’s a story about incredible musical gifts and hard work. Given the symbolism of music, faith, and marriage, it’s also a love story.

Music history leaves a lot of music and musicians out of history. That’s the way it goes for many in the business. But latter-day obscurity rarely reflects ability or passion. It certainly doesn’t have to be the whole story. It turns out that Jack Stillman occupied a fascinating place in music history. This is far from a complete story. Many facts still need finding, connections are waiting to be made, and there is always more to say about the music.

Sources and Thanks (in Alphabetical Order)

- American Dance Bands on Record and Film by Johnson and Shirley

- Bridge of Light: Yiddish Film Between Two Worlds by J. Hoberman

- Discography of American Historical Recordings online

- Forverts (newspaper) archive online

- Fraydale Oysher Yiddish Theatre Collection at Ohio State University

- Harbinger and Echo: The Soundscape of the Yiddish-American Film Musical (doctoral dissertation) by Rachel Hannah Weiss

- Henry Levine and the Recording Trumpets by J.W. Freeman with Levine

- Holocaust and Remembrance in Berdychiv (Ukrainian Center for Holocaust Studies)

- “In Search of Berdychiv” by Stuart Allen

- Jack Stillman: An Annotated Discography by Javier Soria Laso

- The Jazz Discography (online) by Tom Lord

- “Jews and Jazz Before the Beginning” by Henry Sapoznik (lecture at the Yiddish Book Center)

- Klezmer: Jewish Music from Old World to Our World by Sapoznik

- Laughter Through Tears: The Yiddish Cinema by Judith N. Goldberg

- Leonard Kunstadt’s notes and diaries held by the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers University

- National Center for Jewish Film archives online

- New York’s Yiddish Theater: From the Bowery to Broadway by Edna Nahson

- Records of the Hebrew Actors’ Union online at YIVO Institute for Jewish Research

- Ken Regez’s silvershowcase.net

- Tin Pan Alley by David Jasen

- “Ukraine is the Cradle of Klezmer Music…” by Andrii Levchenko

- Uncrowned King of Swing: Fletcher Henderson and Big Band Jazz by Jeffrey Magee

- Visions, Images, and Dreams: Yiddish Film Past and Present by Eric A. Goldman

- Within Our Gates: Ethnicity in American Feature Films, 1911-1960 by Alan Gevinson

- Miscellaneous newspapers, magazines, other periodicals, public records, family documents, and other materials accessed through ancestry.com, archive.org, findagrave.com, newspapers.com, and New York City municipal records online

Thanks to Vince Giordano for his advice on sources; “BH” for taking the time to tell me about his great-grandfather; Colin Hancock for his musician’s insights into these players and sharing Stillman sides; Javier Soria Laso for his considerable knowledge and patience while creating the definitive Jack Stillman discography, and “AK” for providing his perspective as a brass player. Thanks to Michael Steinman for all his editorial expertise and encouragement and Nick Dellow for commenting on my early drafts.