Here’s a modified draft of liner notes I submitted some time ago for a reissue of the Original Memphis Five’s recordings. This essay is longer and more subjective in tone than I now aim for in my writing, but I know a few readers also enjoy their music, so I decided to share the draft in case anyone might want some thoughts on this band. You can also skip my verbiage and head straight for a lot of great music (though many of the recordings listed here were unavailable online)!

Historical information below is from Ralph Wondraschek’s landmark, incredibly thorough research into the OM5, which he published in multiple parts for VJM.

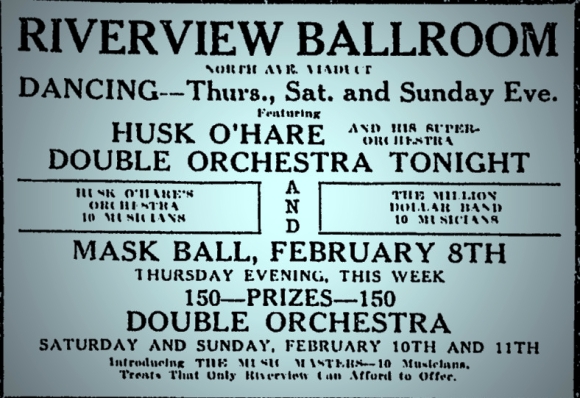

How many orchestral combinations, ten times the size of this quintette of exceptionally capable musicians, can boast that they are making records for eleven different concerns, and are scheduled for weekly appearances in three different dance palaces?

—The Metronome Orchestra Monthly, December 1922

In their heyday, the Original Memphis Five (OM5) made hundreds of records and earned plenty of press coverage. And they’ve enjoyed a decent number of reissues on LP and CD. Yet even with an extensive historical and discographical legacy, it seems like early jazz specialists and hot music aficionados are the only listeners interested in this band.

Musicologist Gunther Schuller devotes one brief (and far from complimentary) paragraph to the OM5 in his landmark analysis Early Jazz. Richard Sudhalter’s Lost Chords gives the group considered musical appraisal (rather than measuring it against more well-known contemporaries). Liner notes by Mark Berresford and Hans Eekhoff for OM5 compilations on the Frog, Retrieval, and Timeless labels also give the OM5 its creative as well as historical due. And several articles in periodicals for record collectors and jazz aficionados do the same. The OM5 also gets plenty of attention on various online social media boards aimed at such specialists.

Still, Smithsonian anthologies and PBS documentaries don’t bother with the band. Most jazz history textbooks omit the OM5. It’s safe to assume many university jazz courses do the same. Miff Mole gets an occasional mention for the influence of his groundbreaking trombone technique, but typically in passing before the story moves on to Jack Teagarden.

Works of jazz history only have so much room, so they tend to include what the authors deem “historic” but not necessarily all of music history. Jazz blogger Michael Steinman analogizes a Biblical progression along the lines of “Oliver begat Armstrong, who begat Roy Eldridge, who begat Dizzy Gillespie, etc.” This approach generates a tidy sequence that explains the music familiar to most listeners today. Yet it offers a narrow picture of the music as it was performed and experienced in its time. Learners are left with an endless history of the avant-garde that emphasizes innovation above all else.

Bands like the OM5 get overshadowed in a form of jazz history that only catalogs the key musicians and events that took the music to new levels. These narratives—overtly or by omission—sometimes relegate the OM5’s music to a well-crafted dance artifact of its time, perhaps beyond reproach but not groundbreaking enough to make it into jazz hagiography. But, as Sudhalter notes, “no band was more universally popular [and] admired on musical grounds” in the early 20s than the OM5. They must have done something special.

The Price of Being Prodigious

Even the most vehement OM5 detractor has to admire the sheer consistency of energy and polish across the OM5’s many recordings. It’s hard to hear the group having a bad day, missing notes, playing sloppily, or performing with anything less than total commitment.

Yet craftsmanship that impresses audiences or even fellow artists doesn’t always win over music historians. Comments along the lines of “X is no Louis Armstrong, Charlie Parker, Mozart, etc.” make for convenient critical copy: superficially discriminating, self-pleasingly flip, versatile enough to use in academic articles or conversation at cocktail parties, and still saying little about either the idol or the supposed also-ran.

The sheer size of the OM5’s discography makes assessment difficult. For some, it even makes the group’s creative credentials suspect. In his liner notes for Retrieval’s reissue CD of the OM5’s complete instrumental sides recorded for the Pathe label (RTR 79044), Mark Berresford points to the unfortunate and unfair dismissal of the OM5 as “slick manipulators of a jaundiced, racist recording industry system, churning out a production line of anemic, soulless records.” The suggestion that this band actually introduced a unique musical style that set it apart from predecessors and contemporaries rarely enters the mainstream jazz discourse.

More Than ODJB Imitators

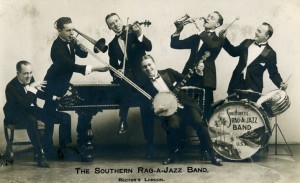

The OM5 was one of the groups that arose in the wake of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band (ODJB)’s immense popularity during the 20s. Passing mention of these “fabulous fives” often implies they were all simply trying to seize upon the ODJB’s commercial success through outright, and at times exaggerated, imitation.

The ODJB, the OM5, and similar groups shared instrumentation of cornet/trumpet, clarinet, trombone, piano, and drums. They all played fast and furious instrumentals full of wild collective ensembles. OM5 pianist Frank Signorelli and clarinetist Jimmy Lytell even became regular members of the ODJB: Signorelli from April 11, 1921, to February 10, 1922, and Lytell from January 14, 1922, to February 10, 1922. ODJB leader Nick LaRocca even accused Signorelli of stealing the ODJB’s arrangements.

Decades later, the OM5 is occasionally mentioned as a transitional step between the ODJB’s more aggressive (yet nonetheless infectious) rag-a-jazz and the looser, bluesier southern and southwestern bands that began recording more often during the 20s. In academic jazz histories, when they’re even mentioned, the OM5 is portrayed as a stylistic placeholder that held people’s attention until they heard “authentic” jazz (whatever that meant at any given moment to each writer).

More than a mere copy or variation of the ODJB, the OM5 expanded upon the ODJB’s approach with a different melodic sensibility and a more measured though still exciting ensemble interplay (and in much better sound due to advances in recording technology, specifically on the Victor and Brunswick labels). The OM5 smoothed out the ragtime-derived phrasing of the ODJB while adding a distinctly New York accent and pushy momentum that was always melodic. “Sob Sister Sadie” surges forward as though the lady can barely catch her breath, but the parts still link together naturally without sounding forced. The OM5’s unity of concept and instrumental clarity never let things spill over into excess.

Hot Lyricism

It is also much easier to pick out a tune on OM5 sides, partially because of better sound on certain labels but largely due to Phil Napoleon’s clear, confident lead. Hundreds of sides demonstrate the cornetist’s powerful but always focused drive, his perfect rhythmic placement, and his sheer beauty of tone—especially on acoustic recordings.

Paradoxically, Napoleon’s sturdy style—a clear melody that doesn’t sacrifice thematic invention or sheer drive—may have allowed later commentators to take him for granted as jazz trumpeters began playing higher and faster. But at the height of the OM5’s popularity, that style must have been advantageous for powerful record companies and music publishers eager to get the actual song heard by as many listeners as possible.

All bands recorded pop tunes, but the OM5, as Napoleon told Sudhalter, “learned them as fast as they published ‘em.” In the OM5’s hands, popular songs are both recognizable and personalized. The now well-known melody of “Everybody Loves My Baby” gets its turn as-is through Lytell’s slurring middle register before Napoleon plays squawking variations on the bridge a la Earl Oliver and Tom Morris. Napoleon’s crisp, relatively unadorned chorus of “How Come You Do Me Like You Do?” still sounds deeply personal.

The sheer frequency of OM5 sessions shows that it was meeting public demand for melody and rhythm while maintaining its own musical style. That style also jettisoned the novelty effects that were so profitable for their contemporaries. Far from Schuller’s assessment of the OM5 as being another group “seduced…away from jazz towards commercial dance or slapstick music,” the OM5’s discography has few instances of barnyard onomatopoeia, kazoo solos, and other gimmicks (and this writer makes no negative value judgments about bands using them). Resisting the fad for novelty wasn’t unique; the Georgians, for example, also avoided these effects on record. But selling so many records without novelty effects set the OM5 apart.

A Five-Piece Orchestra

As a regular gigging band and an active recording group, the OM5 developed a rapport that allowed them to develop and adhere to their musical ideas while sharpening their already impressive musicianship. It’s no small wonder the OM5 always sounds so cohesive.

The verse on “Static Strut,” played with Lytell and Napoleon in tight upper-register unison, is so flawlessly executed that it comes across as a section in a larger band with the agility of a small group.

“Cuddle Up Blues” is just one example of the group’s pinpoint dynamic contrasts.

When the band dips down in volume on “I Never Miss The Sunshine” for Brunswick, the parts remain transparent and swinging: Lytell plays counterpoint in his lower register under Napoleon’s soft muted lead while Miff Mole plays a near-whispering bass line on trombone. At a time when jazz was popularly heard as unrelentingly loud, the OM5 played with a wide dynamic range demonstrating taste as well as attention to detail.

Arrangement undoubtedly played a large part in the band’s consistently unified sound. The use of arrangement/memorization was common at the time. It wouldn’t become a death sentence for authenticity as a jazz player until writers introduced more doctrinaire definitions decades later.

Multiple versions of the hot OM5 original “Great White Way Blues” for the Arto, Banner, Brunswick, Edison, Gennett, and Pathe labels may not yield startling differences in improvisation. Still, they display crack musicianship and a sense of constant spontaneity.

The OM5’s consistent energy level throughout hundreds of sides and engagement with predetermined musical roles may even be all the more remarkable given their intense work schedule.

Regardless of the level of arrangement, the OM5’s credentials as an outright hot band and their unashamedly danceable aesthetic are clear. “Laughin’ Cryin’ Blues” struts from the outset with Napoleon’s lead and witty breaks plus drummer Jack Roth’s rims clicking away in the background. “I’ve Got A Song For Sale” shows a lighter side of the OM5, still danceable but perhaps intended for softer steps.

John Cali’s percussive banjo joins the group on the Brunswick recording of “You Tell Her, I Stutter” to create one of the OM5’s most uninhibited sides. On “‘Taint Nobody’s Biz-Ness If I Do” on Pathe and “If Your Man Is Like My Man,” the band dirties up their otherwise clean timbres, adds a deliberate drag, and inserts inflections as carefully placed musical devices rather than stock effects. On “Evil Minded Blues,” Napoleon plays double-time runs that sound similar to those of the Memphis-born, pre-Armstrong New York jazz trumpet virtuoso Johnny Dunn but with fewer blue notes. The OM5 comes across as unified, even cultivated, even on earthier material.

Authentic To Themselves

The OM5’s tight, well-crafted sound has led some commentators to fault them for a lack of visceral drive or raw emotion. Compared with New Orleans bands recording at the time—such as King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band or even Freddie Keppard’s ragtime-tinged recordings—the OM5’s phrasing sounds more even with more defined articulation and less vocally-inflected timbres. For example, it makes the OM5’s “That Da-Da Strain” seem willfully tense. The Dixieland warhorse comes at modern listeners with a motor energy that now seems to fly in the face of most New Orleans and Chicago-style renditions.

Like fellow New Yorkers such as the California Ramblers and the pre-Armstrong Fletcher Henderson orchestra, the OM5 pushed (rather than rode) the beat with sharp syncopation, adding decidedly instrumental embellishments and insisting on pinpoint note placement. Jazz teleologists are free to sketch a hierarchy of styles. On record, the music is just a different approach to jazz. And in hindsight, the OM5’s style may even be refreshingly unrelaxed. Its two-beat style on “Down By The River” has a more confident, swaggering feel next to the Henderson band’s steady four on its recording of the same tune.

OM5 members likely heard New Orleanians visiting New York City, including Freddie Keppard and Sidney Bechet at Coney Island. Phil Napoleon briefly studied with King Oliver as a young runaway in New Orleans. Trombonist Charles Panely (aka “Panelli”) had played with New Orleanians in the Louisiana Five. Miff Mole even sat in with New Orleans trumpet legend King Oliver’s band in Chicago between February 23 and March 5, 1920.

Yet Lytell, Mole, Napoleon, Panely, Roth, and pianist Frank Signorelli were all native New Yorkers. Garvin Bushell notes in his autobiography that “there wasn’t an eastern [i.e., New York, east coast, non-southern] performer who could really play the blues. We later absorbed it from the southern musicians we heard, but it wasn’t the original with us.” For the OM5, the blues and other folk musical traditions would have been incidental rather than formative. And while many New Orleans musicians trained in the outdoor New Orleans brass band tradition—a unique and popular idiom of the Crescent City—New Yorkers like the OM5 would have been more familiar with the range of theater and dance music popular in the Big Apple.

Why would five musicians sound like musicians from the South? Nearly a century later, do we still need to fault them for sounding like themselves?

Of course, musicians from all regions and communities adapt and learn from various influences. But it’s no surprise that the OM5’s rendition of “Tin Roof Blues” differs from the New Orleans Rhythm Kings (NORK)’s haunting original performance of the tune from just a few months earlier. The NORK is clearly indebted to groups such as King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band. The OM5’s recording instead plays to the band’s unique strengths: tight interplay, crisp accents, and clean, often breathlessly executed musical statements that are as affecting in their own fashion.

The Sum of Incredible Parts

Comparing Napoleon’s open, almost concert-like lead against NORK cornetist Paul Mares’s big round wail or King Oliver’s raspy, muted declarations, it’s easy to fall into stereotypes about conservatory training versus folk traditions, staid and proper northeast versus the earthy South, etc. Or we can look at mere differences of musical priorities and matters of degree when it comes to rhythm, ensemble color, thematic variation, and other musical elements.

Lytell’s clarinet parts are less incisive than the high-flying descant lines of New Orleanians such as Johnny Dodds and Jimmie Noone. His scoops and smears add a different color to the overall sound. Lytell sometimes fills in the harmony from the top instead of creating independent lines decorating over the lead, for example, on “Snake Hips.”

“Red Hot Mamma” for Emerson demonstrates Lytell’s knack for sneaking slick little asides into breaks or between the briefest pauses. For keen insights into Lytell’s musicianship, check out Phil Melick’s liner notes for Jazz Oracle’s reissue of Lytell’s complete trio recordings.

With his superlative technique, Miff Mole could incorporate the tailgate style of the New Orleans trombonists as just one role in an ensemble. On sides like “Chicago,” Mole’s elegantly swinging lines jell with the ensemble with the inevitability of polyphonic chant. His advanced technique and imagination also allow him to range under, over, and around the ensemble beyond the trombone’s traditional role in the three-person frontline, for example, on “Steppin’ Out.”

Panely’s style comes across as more pared down compared with Mole’s. He emphasizes chord tones rather than linear lines and acts as more of a ground bass. Far from being simpler, any arranger would have been proud to pen the ensemble lines Panely lays down on “No One Knows What It’s All About” and “Duck’s Quack.”

On the New York Scene

Listening to the OM5 within the context of its fellow New York City bands brings their musical style into even sharper focus. For example, just as the OM5 is compared with the ODJB, the Original Indiana Five (OI5) is often compared with the OM5. Perhaps trying to avoid sounding like an OM5 imitator, OI5 clarinetist Nick Vitalo doubled on alto saxophone—something Lytell rarely did on record. Proportionately, far more OI5 sides include a banjo. Yet the OI5 did not display the same effortless technical facility (how many bands could?) or balance of instrumental voices.

On “St. Louis Gal,” as just one example, the OM5’s parts lock in with each other and generate momentum and interest inside the ensemble. On the same tune, the OI5’s horns duplicate notes more often, playing in more of a loose heterophonic style than a polyphonic one. The OI5 rhythm section is also more of an accompaniment rather than an interactive part of the front line. As another example, pianist Harry Ford, banjoist Tony Colucci, and drummer/leader Tom Morton mark the beat more deliberately than either the OM5 or NORK on “Tin Roof Blues.”

The Georgians, Paul Specht’s band-within-a-band, were one of the more overtly jazz-oriented groups of the time. Leader and cornetist Frank Guarente was a King Oliver disciple, pianist Arthur Schutt was already translating the spontaneity of jazz into written arrangements, and drummer Chauncey Morehouse could spur and color a band with even the sparest of studio-sanctioned kits. The Georgians’ and OM5’s recordings of “You Tell Her, I Stutter” demonstrate different but equally valid hot sensibilities: the Georgians’ slightly denser instrumental sections versus the OM5’s more transparent ensembles, the OM5’s brighter edge against the Georgians’ richer voicings, Guarente inserting classically-oriented touches amidst dirty, muted lines while Napoleon plays bel canto even in his folksiest outbursts.

Coming out of Memphis and playing with blues composer WC Handy, cornetist Johnny Dunn was bound to apply more blues inflection than Napoleon. Yet overall, Dunn’s records have a more aggressive, military-influenced feel than those of the OM5. Even the OM5’s tense sound on Dunn’s “Four O’Clock Blues” comes across as more playful next to the slightly ponderous but more spacious approach by the composer’s Original Jazz Hounds. And Dunn’s group was also already incorporating a moaning sax section.

A Constant Quintet

The OM5’s loyalty to the five-person jazz band format and eschewal of the saxophone would become a stylistic hallmark (and perhaps a reason for other bands eventually outpacing it in historical hindsight). The Georgians included a sax section with players doubling other reed instruments. Fletcher Henderson was already synonymous with separate brass and sax sections, setting the stage for an orchestral concept of jazz that would change the course of jazz. Since its inception, the California Ramblers, perhaps the most popular New York band of the 20s, exploited the use of the saxophone in sections, solos, and even its rhythm section via leader and bass saxophone virtuoso Adrian Rollini. Even the Ramblers’ myriad small group spin-offs usually included one or two saxophonists alongside a cornetist rather than the standard three-person front line of trumpet, trombone, and clarinet.

As Wondraschek explains, “after the ODJB’s departure for England in March 1919, the saxophone became more and more regarded as an indispensable part of any jazz band. Nevertheless, the OM5 stuck to their instrumentation and managed to become popular without the use of a saxophone. The OM5 were the torchbearers against the then omnipresent trend of increasing the size of the jazz and dance bands.”

The OM5’s Tennessee Ten sides for Victor did include a two-sax section, and some of its Cotton Pickers sides include one saxophone. While the saxes add a contrasting texture, the core OM5 remains the most musically interesting and exciting part: Lytell’s clarinet answers the saxes on “‘Taint Nobody’s Biz-Ness If I Do” and Napoleon’s magnificent embellished lead on “I Never Miss The Sunshine” becomes all the more rhythmically interesting against the straighter saxes. The effect is so pronounced on “Waitin’ For The Evenin’ Mail” that it borders on parody. Trends aside, the five-person lineup could still give those tentets some competition.

The OM5 also proved downright ingenious within the five-person format. Their arrangements did not always rely on New Orleans-style polyphony with a cornet lead, trombone counterlines, and clarinet obbligato. Napoleon cleverly uses contrasting open and muted horn, as in “A Man Never Knows.” He sounds like two different players when he plays the bridge with a muted squawk on “Take Me.” The lead also gets passed around to other instruments, resulting in such novel effects as a brass duet on “Lovey Came Back,” call and response between the front line and the piano on “Papa Blues,” low register clarinet melody with muted trumpet obbligato on “Hot ‘N Cold” and trombone lead with the trumpet playing the melody as an obbligato underneath it on “Cuddle Up Blues.”

Like most bands on record at the time, the OM5 was primarily ensemble-based, so a full chorus of total solo improvisation radically departing from the melody was rare. Passing along the lead allowed for subtle variation, making the theme one’s own without necessarily transforming it or resorting to harmonic refashioning. In this regard, the OM5 resembled other New York-based bands such as Lem Fowler’s Washboard Wonders, emphasizing melodic embellishment rather than a complete reinvention of the tune. This ensemble variety puts the OM5 miles away from King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band, with its leader’s documented rigid division of roles and even register between instruments.

One of the OM5’s favorite musical effects was a break in collective improvisation in the middle of the record for the front line to part ways for a single horn over Signorelli’s accompaniment. Nearly all OM5 records include such a chorus, often with Napoleon keeping the lead but now using a mute for added contrast. These horn and piano choruses add further textural and timbral variety as well as another way to share the lead. They could be heard as an embryonic attempt at contrasting a soloist with the full band, an effect that would become the hallmark of swing-era big bands.

Syncopated harmonized breaks for the entire front line as on “Buzz Mirandy,” “Chicago,” “Loose Feet,” and “My Sweetie Went Away” are another favorite OM5 device that points to later section writing that aimed at sounding like a soloist. Ensemble hits on sides such as “No One Knows What It’s All About” or the harmonized patterns between the trombone lead on “Runnin’ Wild” also anticipate swing big band arrangements. The brass riffs behind Lytell’s clarinet on “I’m Going South” separate instrumental families, an essential sound in Don Redman’s pioneering big band charts.

Brief spotlights for drums also spring up with an unusual regularity for the time. “Gypsy Blues” shows the instant rise that Jack Roth’s drums provide by being strategically deployed rather than relentlessly forward in the mix. “Lonesome Mama Blues” demonstrates Roth’s emphasis on syncopated accents rather than steady beats. “Memphis Glide” shows off his variations on cymbals. Jazz age drummers have suffered the most because of technology, with what little equipment they could bring into the studio at the mercy of recording engineers.

Signorelli is now typically mentioned for playing with Bix Beiderbecke, but his work with the OM5 and frequent features with the group show why he got to play with some of the greatest names in jazz. He plays in a florid, stomping style, often simultaneously accompanying and ornamenting the other instruments. The OM5’s “Farewell Blues” comes off as the most intense version of the tune from this period. Granted, it’s faster than recordings by the New Orleans Rhythm Kings or The Georgians, but the hot factor is primarily due to Signorelli’s pumping left hand and treble fills. His accompaniment for the vocal on “That Red Head Gal” seamlessly underscores the sung melody while bursting into carefree asides. Signorelli seems to have never forgotten his ragtime roots, often relying on bright textures and crisp articulation that add a steady sense of tension and release (even as late as 1955 on an album of duets with drummer George Wettling).

Room For More

Of course, more seasoned ears may simply hear all of this music as a well-crafted artifact of its time, which itself might be enough to earn the OM5 some musical kudos. The OM5 had its own signature sound rooted in creative and impressive musicianship. Other musicians would forever change the course of jazz, but, at the very least, the OM5’s music can now be heard as a fascinating alternative, another unique sound of the historical “scene” rather than a vestigial part weeded out through some form of jazz evolution. Unlike jazz history textbooks, record shelves have room for all kinds of music.