In addition to writing about early jazz and American popular music here, I’m fortunate to be able to cover classical music for Early Music America online. Jazz was actually my gateway to Baroque music, which also features a lot of improvisation, roots in dance, and jaw-dropping virtuosity expressing intense emotions. You can see my latest article for EMA here. I hope you enjoy it.

The Pop of Yestercentury

More Hep Than Hip

Jazz: The Gateway Drug to Classical Music

It’s no surprise that yestercentury’s verdicts on jazz included plenty of praise and lots of bile. New music always gets the same criticisms: lacking quality, spreading immorality, derivative of older music, and a lot of racist claims ranging from veiled to brazen but uniformly disgusting. Yet as jazz spread across the United States and the world, some voices took a middle ground. For them, jazz wasn’t worth the venom. It was neither great music nor a threat. It was harmless fun, but jazz still served an important purpose: helping people appreciate music deemed better than jazz.

One writer spelled out jazz’s edificatory potential in the June 15, 1924, issue of Talking Machine World. Profiling bandleader Henri Berchman, the reporter described a “modern dance orchestra” that took pride in playing both popular and classical works. This band appealed to audiences who were “interested in real popular music and, at the same time, have an inborn taste for better things.” These “better-class orchestras” would “lead those of strictly popular taste into an appreciation of the classical.”

At least jazz haters assumed the music had some power; people don’t mourn the loss of artistic standards or forecast the downfall of civilization unless they perceive a threat. This didactic assessment of jazz doesn’t even give the music that much credit. Jazz is not a threat; it’s homeopathic music appreciation. Judgments like these seem more surprising for their effortless condescension.

The August 1924 issue of Etude magazine, dedicated to “The Jazz Problem,” is like a compendium of contemporary outlooks on jazz. Its descriptions ranged from music for a country that lost its soul to conductor Leopold Stokowski hearing jazz as “new blood [flowing] in the veins of music.” Ironically, Paul Specht, one of the most popular bandleaders of the time, neatly summarizes jazz apologetics:

This form of music is a forceful stepping stone to stimulate interest in the study of music; a step of musical development, distinctly American, that is teaching the public to better appreciate our big symphony orchestras.

Paul Whiteman takes the perspective a step further, suggesting his music opens audiences to other pieces of high culture:

We cannot expect the man in the street, with a Police Gazette in his hands, to pay a large price to see Ibsen’s Ghosts. He must be educated up to Ghosts. He will be fascinated by jazz and use it as a suspension bridge to better things.

Whiteman was one of the most successful popular musicians in American history. He also frequently defended popular taste. In his book Jazz, Whiteman makes a lengthy point about good taste and popular demand not being mutually exclusive, insisting that “the so-called masses have considerable instinctive good judgment in matters of beauty that they never get credit for.” He’s also skeptical, almost resentful, of “certain high and mighty art circles.” Whiteman advises that “the Denver [Whiteman’s hometown] boys who haven’t grown up to conduct orchestras and police reporters who haven’t got jobs as critics have sound opinions, too, and we ought to listen to them.”

It’s not that strange to hear Specht and Whiteman advocate for their music as a path to high art. They were key players in the growing popularity of jazz-influenced dance bands. They also saw these bands and their arrangements grow in size and complexity. Specht, Whiteman, and other bandleaders probably just understood which elements of their music might appeal to the elitists. They didn’t make music to pander to longhairs, but creative pursuits and marketing sometimes align.

Some members of the musical establishment found symphonic jazz and imaginative “special” arrangements promising. Composer and critic George Hahn heard the development of bigger bands and more sophisticated arrangements as jazz finally “being done artistically.” In his essay “Modern Arrangers Are Synthetic Composers” (Jacobs’ Band Monthly, September 1923), Hahn notes how “the erstwhile blatant jazz has given way to smoothly flowing, beautifully voiced harmony and rhythm” thanks to “arrangers and directors who took the raw jazz as it came from New Orleans and change[d] it into the aristocratic variety we have today.”

Hahn thought jazz could redeem itself through advanced compositional techniques and curbing improvisation. Others still heard a means to a higher end. In his essay for Etude, composer Percy Grainger compliments jazz for advances in instrumentation comparable to those of Beethoven and Wagner. Grainger goes as far as describing jazz as “near-perfect and delightful popular music and dance music.” Like all dance music, it provides excitement, relaxation, and sentimental appeal.

Grainger’s description might seem like one of the more charitable ones. Yet alongside his confusing, borderline offensive pseudo-ethnomusicology (i.e., jazz as the “combination of Nordic melodiousness with Negro tribal rhythmic polyphony”), he declares jazz some of the “finest” popular music in history but “nothing more.” Grainger comes off as pompous rather than antagonistic, and more insulting for it:

The laws which govern jazz and other popular music can never govern music of the greatest depth or the greatest importance…The world must have popular music…But there will always exist between the best popular music and classical music that same distinction that there is between a perfect farmhouse and a perfect cathedral.

To Grainger, popular music doesn’t make demands on the listener, while classical music demands “length and the ability to handle complicated music,” signs of superior intelligence. He allows that jazz can help educate children, but parents and educators must ensure youngsters also “drink the pure water of the classical and romantic springs.”

This is praise with damning consequences. Grainger consigns jazz to (at best) an educational role, while remaining a diversion for simple minds. If any adults are listening to jazz, they’re free to enjoy the farmhouse, but they only get to Heaven if they can find their way to the church. The imagery of purity—presumably versus dilution or even pollution—feels especially ironic from a composer known for experimental music that explicitly rejected traditional classical structures and his pioneering role in folk music revival.

These are just a few examples, and they were less prevalent than outright condemnation, but arguments for jazz as classical music’s training wheels emerged often enough. They form a unique corner of the early reception of jazz. They share the same focus on cultural hierarchies as the outright condemnations. Still, their patronizing equivocation lets some music squeak through, music that people who heard Ted Lewis and Paul Whiteman as equally hateworthy would never allow.

It’s no accident this line of thought coalesced around a lot of music many now consider at the margins or completely beyond jazz. The overwhelmingly white composition of jazz commentators at the time will either seem predictably offensive or still shockingly ignorant. The word “jazz” covered a lot of musical and cultural ground during the twenties. Yet whether it was Duke Ellington, Paul Whiteman, Joe Oliver, or Earle Oliver, the harshest critics seemed to be battling for the country’s soul. This high-handed middle ground seemed to be waging a cold war for America’s brain. Neither campaign was needed. At least judging people based on their taste is a last-century problem.

Selling Songs and Commercial Creativity

At least by the time of his sixth musical, Jerome Kern was no fan of jazz. According to the “Melody Mart” column in the April 26, 1924, issue of Billboard magazine, jazz drove the Broadway composer to bar publishers from printing orchestrations of songs from Sitting Pretty, Kern’s newest show.

It was partially an economic decision. Sheet music, record, and theater sales were crashing. Many blamed radio for offering too much free music. Audiences supposedly got sick of the latest songs too soon. With Kern’s embargo, the only place to hear numbers like “Shufflin’ Sam” and “Bongo on the Congo” as envisioned for the stage would be the stage. In theory, demand at the box office, record shop, and your local sheet music seller would shoot up.

Yet this was about more than the bottom line. Kern was a composer as well as a businessman. He wanted his music performed as he wrote it:

By keeping his numbers away from jazz leaders, who mutilate the music, sheet music sales of the show numbers will be fair enough due to the patron who hears them in the production … [Kern] was against the jazz orchestras butchering a song so that the public never knew what it really was … There was no way to prevent the so-called special arrangements being made by phonograph record artists who wanted and had to be different.

People could buy lead sheets with lyrics and piano accompaniment, but jazz musicians wouldn’t find stock arrangements waiting to be mangled with their improvisations and slick effects.

Discouraging musicians from following their creative instincts, demanding they stick to a written part, privileging published composition over bandstand invention: It might be the triumph of crass commercialism and mass culture over artistry. Yet it might also reflect something less cynical and much simpler, a musical ideal as common in the 1920s as the 2020s, something that proud songwriters and the average Jazz Age music consumer could both agree on: hearing a tune.

Supply and Demand, Creativity and Taste

Kern and his fellow songwriters considered themselves artists, too. They also wanted to create music for audiences to enjoy. Jazz blogger (and my dear friend) Michael Steinman points to Richard Rodgers and lyricist Lorenz Hart making their demand literal and singable in “I Like to Recognize the Tune.” In his autobiography, Rodgers elaborates on the philosophy behind the song’s pointed title:

We voiced objection to the musical distortions then so much a part of pop music because of the swing band influence. We really had nothing against swing bands per se, but as songwriters, we felt it was tough enough for new numbers to catch on as written without being subjected to all kinds of interpretive manhandling that obscured their melodies and lyrics. To me, this was the musical equivalent of bad grammar. On the other hand, once a song has become established, I see nothing wrong with taking certain liberties. A singer or an orchestra can add a distinctive, personal touch that actually contributes to a song’s longevity. I can’t say I’m exactly grief-stricken when something I’ve written years before suddenly catches on again because of a new interpretation.

Popular musical styles had changed by the time the song was published in 1939, but the sentiment remained evergreen. The difference was that many American popular standards were not yet “established” during the twenties. Songwriters at the time might’ve felt like an author watching a film version of the novel they just got published.

Tin Pan Alley was a huge commercial complex. An entire industry of composers and lyricists supplied romantic songs, dance numbers, novelty tunes, topical ditties, and anything else people could sing, dance, relax, laugh, neck, or cry to. But the music industry was also a creative site. Some people worked hard and took pride in their product—even if it also allowed them to pay rent or buy a second Packard.

On the other side of supply, there was demand from audiences, who weren’t looking to make anyone rich. Some just wanted good lyrics set to a catchy melody. Others were more discerning. Both reflected preference for song.

Ironically, by the beginning of the Jazz Age, many dancers and listeners wearied of wild improvisations and careening ensemble lines that obscured the tune (while, of course, many others couldn’t get enough). By December 1921, Dance Review reported that “artistic, refined effects” and “carefully worked out novelty choruses” were already overshadowing “loud ‘jazzy’ playing.” William Howland Kenney points to one editorial, titled “The First Fight on Jazz” in the New York Clipper of August 16, 1922, that captures the outcry for a clear tune:

A popular tune is played by one of the jazz orchestras. The orchestration for it has been furnished by the publisher at a considerable cost, but as rendered by many of the orchestras, few that had heard it in the song form or played on the piano would recognize it … A well-written melodious number is so buried under the jazz antics [emphasis mine]…the audience can scarcely recognize the melody.

Popular tastes constantly change, yet this trend was toward the status quo: a solid tune. The frantic counterpoint associated with the Original Dixieland Jazz Band and its imitators was already out of fashion when Kern issued his edict. Large dance bands with brass, reed, and rhythm sections using written arrangements became popular. By November 1926, Orchestra World was covering Tom DeRose’s five-piece New Orleans Jazz Band as a throwback to “good old Dixieland-style jazz” that still played “the more barbaric type of syncopation.” The five-piece ODJB took the country by storm only a little over a decade earlier, a lifetime in American popular music.

Pragmatic music industry officials also had a stake in a solid tune. David Jasen describes this as an era when a song’s publication was more important than its performance by a particular artist. A song was successful if it sold sheet music and records. Several bands might record the same tune for different record labels. Music lovers might buy any recording they could get; they just wanted to hear the song. Yet, as Kenney notes, “jazz polyphonies even endangered the well-established musical arrangements that turned out hit melodies.” He meant more than arrangements on stave paper:

Record companies paid royalties to the sheet-music publishers whenever they issued a recording of a published song. According to Variety, recording company studio managers kept lists of numbers they wanted to record and invariably passed the list first to “the[ir] premier orchestra” which picked all the “hit numbers, that is, tunes that had already sold exceptionally well in sheet-music form.”

A complex industry thrived on literally selling songs. To business stakeholders, if the public was paying attention to a band, they weren’t necessarily focused on the tune. Following that band’s gigs or buying every record they cut didn’t necessarily yield the publisher any direct royalties.

With recording companies eager to keep their slice of the market, business interests viewed bands as vehicles for their tune (not the other way around). Studio ensembles proliferated: house bands and musicians contracted specifically for record sessions, recording Tin Pan Alley’s constant output, often steered in more conservative musical directions.

These may sound like suboptimal conditions for jazz or any form of personal creativity. Yet musicians don’t stop being creative when they read (or write) music. So-called commercial musicians came up with some clever, if sometimes ultra-subtle, musical ideas. The alleged constraints inspired some inventive music.

Variation Through a Theme

If you have to repeat a melody, switching up who plays it goes a long way. Instrumental timbre provides one of the simplest but most powerful joys of music. The best dance records of the period display an impressive degree of variety using “just” the tune by changing orchestration, rhythmic accompaniment, and instrumental texture between and even within strains.

Other arrangers leveraged these ideas while taking greater thematic liberties. Some soloists developed the song into brand new melodies while expanding on the harmonic possibilities of the underlying chords. Yet the best “commercial” arrangers choreographed instruments while keeping the tune front and center. Nathan Glantz’s rendition of “By the Light of the Stars” is a great example.

Recording for Edison as the “Tennessee Happy Boys,” Glantz and his band stay close to Arthur Sizemore, George Little, and Larry Shay’s Tin Pan Alley piece. They lodge it firmly in listeners’ heads. Publisher Jerome H. Remick might have thought this was simply a band doing its job, but I’ve also had the sound of Glantz and his band playing the song stuck in my head for years:

On the first chorus, the tenor saxophone plays the lead softly in long, lyrical lines that would fit in a hotel ballroom. The trumpet syncopates the lead on top without losing the tune. Playing the unadulterated melody as a foundation, the trumpeter can take greater liberties without “mutilating” the tune. It’s a simultaneous straight and hot treatment.

At the bridge, the alto sax bends and elongates the melody with jazzy licks but never discards it. The trombone and ensemble split the verse, trombone laying down the melody right on the beat and answered by raggy trumpet. The sax section pares the next chorus down to clipped accents over a shuffling accompaniment; the song is still there, just more by implication than full recapitulation. The trombone adds a gruff surface to the bridge, the alto sax is more lyrical on the verse, and the soprano sax’s bright, gooey color almost parodies the chorus. Yet it’s still easy to hum along with each segment. The tune is now familiar enough for the tenor sax to answer the ensemble’s stop-time reduction with looser hot phrases. By the end of the record, all melodic fetters are off, and the trumpet plays even hotter over cymbal backbeats.

The record balances composition and arrangement, the composer’s codified work and the musicians’ contributions, theme and variation. It’s a hot record, but for a listener looking for clear melody and a steady beat, it splits the difference and maybe opens their ears to other possibilities.

Discographer and musician (as well as generous and knowledgeable expert) Javier Soria Laso says this is a stock arrangement, perhaps doctored by members of the group. If the shifts in instrumentation and subtle melodic/rhythmic alterations were part of the published orchestration, that just reveals a subtle hand at work. Every stock arrangement has an arranger behind it, and even the straightest of straight melody statements still needs a musician to play it.

The Art of Compromise

In jazz (as it’s commonly discussed today), the term “soloist” is often reserved for a musician extemporizing on the harmonic material of the song. Among historians and fans of early jazz, “hot solo” usually implies the melody was just a catalyst for the soloist’s ideas.

So-called commercial musicians didn’t have either option. Yet that didn’t necessarily preclude creativity. Some thrived on the subtlest melodic paraphrase: crafting slight rhythmic and melodic alterations—hesitation, anticipation, elongation, ornamentation, articulation, doubled notes, timbral variation, etc.—to play with a song even as they kept playing the song.

The best hands turned even a “straight lead” into a personal statement. The trumpet’s opening chorus on “Chloe” with Sam Lanin (d.b.a The Gotham Troubadours for Okeh) offers a master class in pinpoint inflection, embellishments, and slight rhythmic adjustment:

If a recording even allowed room for getting hot, it was definitely not on the first chorus of a new song. Yet even composer and publisher Charles N. Daniels (a.k.a Neil Moret) might have appreciated the way this trumpeter delivers his work. It’s clothed in a warm, smooth, harmon-muted sound. Ornaments and rhythm add momentum to the melodic line while keeping things singable. Syncopations on the second eight bars of the chorus sync with the brighter harmonies before a descending run complements the sax section’s ascending run when they take over.

Of course, the idea that “it’s the singer (not the song)” isn’t unique to any form of music. Jazz, in particular, always had an affinity for it, going back to New Orleanians’ “ragging” a tune. There are countless examples of what Gunther Schuller, after Andre Hodeir, described as “a type of improvisation based primarily on embellishment or ornamentation of the melodic line.” Composer, instrumentalist, and music historian Allen Lowe explains how musicians ranging from James Europe’s syncopated orchestras to Earl Fuller’s defiantly chaotic take on the Original Dixieland Jazz Band “used phrasing and rhythmic variation as a means of pre-jazz invention before moving to the next step, which was to restructure melody as contained and related to the accompanying harmony.”

Maybe the trumpeter on “Chloe” was literally improvising (i.e., doing things on the spot), but it’s a different concept than what Lowe and Schuller describe. The proportion of musician-to-song feels different. The song isn’t source material; it’s the song. The song and the musician are not equals. The musician’s ideas are not the (main) point, yet there they are. If ears could squint, we’d “see” this trumpeter. It’s like virtuosic self-effacement.

The Threshold for Individualism

This example is from a record that might be described as “commercial music” of the period. It’s telling that Brian Rust’s jazz discography doesn’t include it. With his idiosyncratic distinctions between “jazz,” “dance music with obvious jazz flavoring,” “dance bands” playing all varieties of music, and other categories, Rust might have heard “Chloe” as “straight dance music,” something that “does not deviate as much as a quaver from what is written in the score.”

This trumpeter had to sell that tune. Their knack for melodic paraphrase might be so subtle as to seem inconsequential. Still, it’s unlikely they were reading those inflections, embellishments, and slight rhythmic adjustments off the page. It begs the question of how much variation is needed to qualify as “improvised, original, creative, etc.” If you are coloring within the lines, you can still pick the colors. The lines might even inspire you.

As for the demands placed upon these musicians, they might feel like a limitation or even a violation. To some players at the time, it was just part of a job. Others would recollect how much these convictions chafed at them. Later musicians and listeners might even assume that liking—or even preferring—this sort of thing is objectively unhip.

Musicians tamping down their creativity for the sake of commercial interests and a supposedly unadventurous audience is one of the oldest and saddest tales in the book. But for at least a few, it may have been a unique challenge or simply a different means of expression:

In some of our sweet arrangements in Tommy Dorsey’s orchestra, we get a chance to express our feelings, and when we carry the melody, we just sing it out as if we actually were vocalizing. It also means that you have to feel your music, too…

—Hymie Shertzer, “Tells Technique of the ‘Singing Tone,” Metronome, April 1940

If it wasn’t jazz, it wasn’t always a compromise. Some people even liked it.

Thanks so much to Colin Hancock for sharing his thoughtful ideas on this subject!

George Frazier’s Warning to Jazz Purists

If a critic makes an innocent typo today, you can leave a comment, post a response, or email an entire argument. Yet the critic who slammed your favorite album decades before your birth can’t even get a curt letter. Ironically, their comments might be the most grating. Yesterday’s criticism sometimes calcifies into common wisdom.

Take George Frazier’s record review column in the December 1933 issue of Jazz Tango Dancing. It includes coverage of Columbia 2835-D: two sides by Benny Goodman directing a studio group including Gene Krupa, Joe Sullivan, and Jack Teagarden. Today, it seems like a pickup group of legends in the making. At the time, it was a new record to review, and it didn’t impress Frazier.

He compliments all the familiar names. Tenor saxophonist Art Karle earns special praise. Frazier also gives Columbia credit for its recent jazz releases. He’s otherwise dismissive of both “I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues” and “Ain’t Cha’ Glad.” The review ends by pronouncing the disc “far superior to the general run of current American recordings,” but that’s an afterthought. Immediately before, in the second-to-last sentence, Frazier warns that “it would be wrong to imply that this disc is absolutely without any commercial taint.”

There’s nothing unusual or elitist about assessing jazz content for a jazz magazine. But Frazier goes beyond stylistic analysis. He’s not just suggesting readers endure those parts. He’s providing a warning. This jazz is “tainted” with popular elements. It’s the aesthetic equivalent of noting the presence of gluten to someone with celiac disease.

He singles out Teagarden’s concluding cadenza on “Ain’t ‘Cha Glad” as “a display of technique rather than [an] intrinsic hot break” right before bringing up the commercial contamination. Maybe the muted trumpets behind Goodman’s first chorus reminded him of “sweet” bands—another category established by filtration from what Frazier later calls the “true hot.”

It’s harder to parse the objections to “I Gotta’ Right to Sing the Blues.” Frazier might have disliked its arranged introduction, prominent ensemble backgrounds, or the big theatrical band climaxes at the end of soloists’ phrases. He also finds Teagarden’s voice insufficiently rich.

Maybe Teagarden was mellowing his sound for this pop tune. A knowledgeable friend points out that Goodman kept his ears on the market. The musicians may not have noticed or even cared about the commercial connotations of Arthur Schutt’s arrangements. Maybe they appreciated touches like the coppery brass pecks behind the warm grain of Goodman’s clarinet. Goodman, Krupa, Schutt, and Teagarden worked together regularly. It’s unlikely anyone was complaining about playing these charts.

Were these musicians adding these touches to achieve a pop sound? Or were they simply musicians making musical choices who happened to be waxing a record aimed at a broad audience? Were any of these labels on the musicians’ minds? Did Teagarden simply need a glass of water? As this friend also points out, these gentlemen may have been grateful just to play music for money during the Great Depression.

Frazier likely didn’t have room to outline every offending touch, and it might have been unnecessary. There was enough there—meaning anything there—to remind listeners of other music that wasn’t hot or hip. Frazier wasn’t the first or last critic concerned with purifying jazz of its commercial contaminants, but this is a pristine sample in the archaeology of this critical tendency.

That tendency arose for valid reasons. Scholars often point out that the word “jazz” was once a marketing term as well as a musical label. It signified both Johnny Dodds’s and Ted Lewis’s clarinets. Some people just thought of Lewis’s top hat and stage comedy. Jazz lovers like Frazier had seen promoters, fans, journalists, and even musicians label almost any form of upbeat popular music as “jazz.” By 1933, if not sooner, enough seemed to be enough for them. They wanted to set the public straight. They had to filter out “commercial” elements from an art form they loved that was still in its early stages of development. Frazier was helping people find real jazz and avoid—or at least be aware of—pop filler. It’s criticism as a buying guide, a consumer report for art music.

Opinions like these trickle down and embed themselves in discussions about music until they seem basic to the conversation. Gunther Schuller published Early Jazz three and a half decades after Frazier’s article. Reading Schuller’s book 60 years later, the stakes go beyond taste. Schuller mentions the “intrusion” by or the “intruder” of “Tin Pan Alley,” “commercial popular music,” and similar music throughout the book. Noting that “the first inroads of popular music into jazz” came early in the music’s history, Schuller surmises that “it was as if pop music and commercial interests had been standing by in the wings, ready to move in on the fledgling music.”

The implication was that, during the twenties, a calculating, even predatory, entertainment industry forced things that didn’t belong into jazz without the creative input of jazz musicians. Seen in this light, enjoying a pop act is more than square; it’s fraternizing with the enemy. Pity the poor musicians who wanted to play the stuff.

Early Jazz is now one of the most influential works of jazz history. 50 years after Frazier’s passing, this sharp distinction between “pop” and “jazz,” between commerce and art, remains popular enough. People like to dismiss criticism, and someone’s distaste shouldn’t affect your taste, but it’s interesting to note how often you slip on the spilled ink.

More recently, in 2023, one scholar noted that “in the 1920s, jazz arranging gave white men the ability to own and accumulate musical property and therefore expand their control over the market.” There’s a lot to discuss in this single phrase, let alone the rest of the paper. The cultural issues behind jazz history are important, and this paper focuses on a broader discussion of them.

Yet this statement resembles a common musical argument about this period: bands got bigger, arrangements got more complicated, everyone was trying to get in on the jazz act, and audiences couldn’t discern the musical quality of Paul Whiteman versus Duke Ellington (which is like asking someone to say which love story is best).

To this scholar’s credit, other parts of their paper critique the assumption that arrangement is by definition commercial and antithetical to real jazz. They also don’t rule out the possibility that people can have profit motives and creative goals. Yet some critics are not as fair. To some listeners, it doesn’t take much to stamp a musician as a sell-out, and why bother listening to a sell-out?

These are some particularly illustrative but admittedly isolated examples. There are plenty more in academic journals and internet forums. In contrast to these assumptions about commercial music, bandleader Harold Leonard had high hopes for music that was sonic furniture to many people.

As Colin Hancock’s outstanding bio and playlist explain, Leonard was an incredibly popular musician in his time, leading a band that could get hot but likely didn’t achieve commercial success strictly playing jazz. In a column directed specifically at musicians leading hotel dance orchestras, he closes with a section titled “Leader Must Like His Work,” advising his fellow working musicians to respect the music even as they watch their bottom line:

Before closing, however, I want to stress one important point—the dance orchestra leader must be sincere. He must have a constant interest in his work, a love for it akin to that of the leader of a symphony orchestra. He must appreciate and study the music he plays and concentrate on the methods which he thinks will aid in the betterment of his orchestra’s playing. Only in this way can the dread monotony, the feeling of “the same old thing” that has brought grief to many a good orchestra, be avoided. The orchestra leader must be so intensely interested in his work, so absorbed in a constant attempt to improve the playing of his orchestra that any feeling of monotony will be lost in his love and appreciation of the work he is doing.

Frazier might have hated Leonard’s music, but even he would have appreciated the intent behind it. The supposed “taint” of commercialism could have just been different but equally sincere music. Whatever the commercial sound is at any given time, does it also get to be sound?

Leo Reisman and Dance Music for Listeners

Leo Reisman is probably best known among jazz aficionados for featuring Bubber Miley both live and on his Victor recordings. An important collaborator with Duke Ellington and influential trumpet stylist, Miley had to play behind a screen with the white bandleader-violinist on live dates. Nearly a century later, Reisman usually comes up in discussions about disgusting racial politics or as the bandleader who happened to be there for Miley’s searing outbursts, like those of “Puttin’ on the Ritz”:

As for the rest of Reisman’s music—hundreds of records and some film appearances across an active musical career spanning decades—he more often played sophisticated dance music in commercial settings. Record collectors sometimes note that while Reisman could get hot on record during the twenties, he later segued into (relatively) sedate, lushly arranged music. For at least one commentator, this meant “abandoning the jazzy hot dance arrangements of the 1920s and turning to more banal, traditional ballroom sweetness.”

Some of Reisman’s music may have been labeled “jazz” during the twenties. A century later, there are important cultural and critical distinctions between jazz by the likes of Ellington and Louis Armstrong versus jazz-influenced popular artifacts once deemed “jazz,” not to mention music well outside the tradition by Reisman and others. In fact, most historical discussions of popular music don’t mention Reisman. Yet a contemporary profile allows some insight into his music (as opposed to its social context or the leader’s popular appeal and financial success).

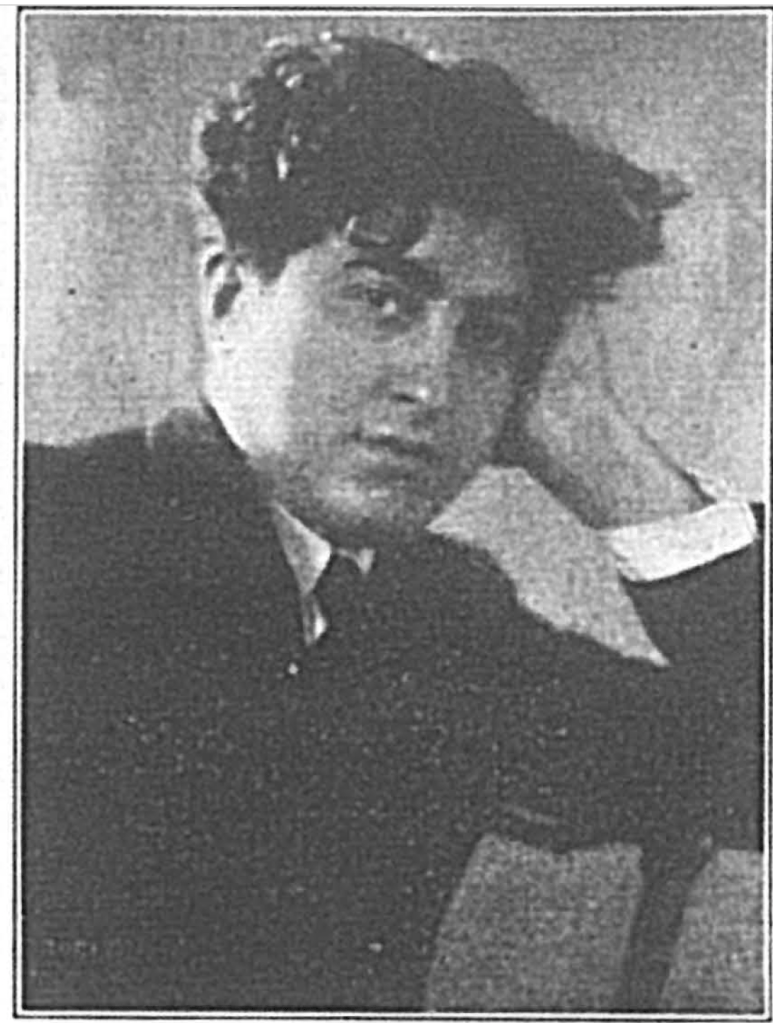

In an article for Jacobs’ Band Monthly of November 1925, George Allaire Fisher singles out Leo Reisman as “the most successful, artistically [emphasis mine], of the many popular orchestras that are now so busily engaged in this broad land of ours in churning up sound waves.” The caption to the accompanying image of Reisman—posed like a pensive intellectual and determined artist with tumbling hair, head resting on an outstretched palm, and a reflective but calm stare into the camera—says that he “demonstrated the broad difference between ‘just [emphasis mine] jazz’ and ‘modern American music’ artistically presented.” Fisher also praises Reisman for “dance music played so that it was at the same time as musically interesting and as intriguing [as] a dance rhythm.”

The praise rests on some elitist assumptions. There’s unfair (but common for the time) minimization of jazz. There’s also the implication that musical interest and danceability are two separate but unequal criteria. Fisher doesn’t disregard dancing; he even quotes the respected classical pianist Mischa Levitzki declaring Reisman’s work as “the best dance music [he] ever danced to.” Composer Darius Milhaud shared this opinion. But Fisher positions musical interest—pure formal listening—over dancing. There’s real deal musical appreciation, and then there’s this enjoyable activity that doesn’t get music in some absolute sense. Even Fisher’s choice of sources seems intentional. The implication is that dancing is fun, but these authorities from the world of European art music know art when they hear it.

This elitism feels ironic given Fisher’s elevation of popular music to an aesthetic object. He offers critical admiration for an orchestra playing popular tunes for dancers and shows. He’s not just profiling a band that rakes in cash and fans. He’s analyzing what makes their work musically worthwhile. For example, he describes the band’s “beauty of tone color… variety…symmetrical precision, melodic beauty…proportion…balance in instruments and arrangements.” Beyond having a good beat, Fisher unpacks what he hears under all the tapping feet:

While maintaining a steady rhythm, Reisman secures the effects even of rubatos and accelerandos by the way in which instruments are balanced against each other and by the subtlest sort of syncopation. He moreover uses every possible effect of tone color, shading, melodic variation, and dynamics so that there is a continuous but always pleasing variety … He also plans the rhythm and dynamics so that the music has a lift between the strong beats rather than a thud on each strong beat … the effect of the music is to carry them along …

Fisher’s use of technical terms, discussion of dynamics and other musical details, and his attention to the level of thoughtfulness in this music probably surprised many readers. This was popular music (as opposed to “serious music”). The suggestion that popular music could be serious probably confused some readers. It likely confused Fisher’s colleagues at Jacobs’ Band Monthly. Several of them thought that only conservatories and concert halls offered music worth considering as music. They certainly said so in their columns.

The Leo Reisman

The rejection of American popular music at the time included what many called “jazz,” whether it meant Louis Armstrong, Ted Lewis, or Leo Reisman. Jazz has now mostly shed its associations with popular music. We hear it in conservatories and concert halls. We read musicological analysis of Armstrong’s music once reserved for the likes of Bach. Reisman played symphonic, through-composed dance music that is largely forgotten in historical discussions. The suggestion that he could be “better than jazz” might now seem preposterous.

At the time of Fisher’s profile, Reisman and his band were playing at the Hotel Brunswick in Reisman’s hometown of Boston. The 28-year-old violinist was already an industry veteran. He began plugging songs in a music store by age 12, attended the New England Conservatory, and briefly worked in Baltimore as a symphony musician and salon orchestra leader before coming home to continue leading dance bands. By 1929, he was playing fancy spots in New York City while recording for Columbia and broadcasting over WBZ.

Reisman was also a cultural pioneer. In addition to hiring Miley, Reisman featured Johnny Dunn in his “Programme [sic] of Rhythm” concert at Boston’s Symphony Hall on February 19, 1928. Some audience members walked out to protest a Black musician playing onstage with the band. But critic and dancer Roger Pryor Dodge remembered Dunn playing “East St. Louis Toodle-Oo” as the only highlight of hearing Reisman, who otherwise only played “the most discouraging trash…the same attempt to use [jazz] without respecting it.”

Reisman was not a jazz musician. Improvisation, the blues, and the unique rhythms of jazz were not his priorities. Yet he was a musician with his own musical priorities alongside his business motives. He outlined these priorities and advised dance band leaders and musicians throughout a series of columns for Jacobs’ Band Monthly. Reisman had ideas about dance music. It was not just a way to make a living or get his name on the marquee.

Plenty of listeners stop Reisman’s recording of “What is This Thing Called Love?” right after Miley’s full chorus paraphrase solo. Some wait until after the vocal to hear his obbligato behind the vocalist. They’re there for the jazz. The “sweet” stuff is too often dismissed as commercial filler that jazz artists had to endure.

Miley gets plenty of space on “What is This Thing Called Love?” But the ensemble work reminds us that the “filler” was the livelihood and craft of musicians like Reisman:

After the vocal, soft strings, with maybe a flute in the mix, create a thicker texture and slightly louder dynamics. Up to this point, the surface texture has been light: just trumpet and vocal with a few light violin tremolos and a prominent bass. The strings prepare the way for the full ensemble. The verse can sometimes seem like an afterthought, so introducing both the full band and the verse in one sweep makes an impact. It also introduces a purely symphonic effect, contrasting with the jazz solo and sweet vocal with jazz accompaniment. The subtone clarinet adds more atmospheric contrast; we start with hot lyricism and end with whispering introspection.

The whole thing is so well choreographed in its exploitation of texture and scale. The carpet of strings, dramatic crescendos, and ballroom-friendly atmosphere may not work for everyone. But they do work on their terms.

Ironically, a romantic title like “Twilight, the Stars, and You” shows us the hotter side of the Reisman band and a possible peek into what Fisher heard around this time:

This might be what Dodge meant by “use [of jazz] without respecting it.” There’s a solid beat for dancing. It doesn’t have the same elasticity and accent of jazz, but it’s far from sleepy. There are saxophones, the quintessential jazz instrument of the Jazz Age, but they’re playing smooth, legato melody over pumping bass with crisp brass syncopations. The sax and violin duet doesn’t try to be jazz. Instead, it spins ballroom melodic deconstruction: the sax keeps the tune available to the listener the whole time while the violin takes it apart.

There’s some hot trumpet followed by violin and woodwinds, cooling things down. The trumpet returns, muted and soft, right before a rhythmic ensemble. A clarinet obbligato injects more jazz flavor, but things end on a chiming piano coda. The arrangement lets the musicians and dancing listeners have their hot and get their sweet, too.

On the other hand, “Just a Gigolo” may be what collectors who lament Reisman’s later work had in mind. It’s as sweet and symphonic as it gets—but not banal:

A muted trumpet hints at the melody over descending winds, starting the record on a curiously suspended feel for a dance record. A brighter, clarinet-led sound finishes the intro before the first chorus with strings. It’s tempting to dismiss this as sentimental, generic, or dated. Still, the violins’ slurred articulation makes the melody sound like it’s intoned through a resonator. Things become popular for a reason.

When the brass takes over the next chorus, they’re backed by reedy saxes (perhaps led by the tenor). Brass over saxes is nothing innovative per se, but the sections are not in dialogue like on a Fletcher Henderson chart. They’re massed for a voluminous effect that makes this already expanded band sound even bigger and richer. A symphonic-style transition leads to the verse, where those brawny saxes take the lead with lower brass adding further depth. And we’re only halfway through the record.

The level of attention devoted to cutting a three-minute record is inspiring. Critics may describe this music as “over-arranged,” which begs the question of whether music can ever be over-improvised. Of course, it all depends on the music.

Music That’s Also Popular

No one would expect a jazz documentary to include Reisman. Most of his repertoire did not sound anything like jazz as it’s commonly understood today. Jazz purists sometimes reject his music for that reason. Unsurprisingly, jazz musicians of the time (just like today) were less doctrinaire. Some were just earning paychecks. But interviews and diaries show that many musicians enjoyed playing in different musical environments.

Reading some later coverage, it can seem like this was music exclusively for brainwashed consumers shuffling background music at social events. But the attentive dancers who appreciated the sounds on top of a steady beat; the listeners, seated and dancing, who savored the musical details; the musicians who enjoyed the music (and the steady gig): they all heard something.

Especially in the pre-rock era, jazz had a significant impact on American popular music, and many musicians moved freely between the two worlds. These interactions between jazz and popular music may earn the latter a passing mention in jazz histories. But for some jazz historians and writers, these are compromises (not exchanges). They hear jazz influences in popular music as “close-but-no-cigar” imitations or shameless appropriation.

You can find examples of subpar music in any genre, and there are plenty of people ready to dissect them, but analysis of the best work may be swept aside. That includes many dance bands; big bands (as opposed to “swing” or “jazz big bands”); studio orchestras; and even so much well-orchestrated, sincerely performed music filed under “Easy Listening” by the local download conglomerate. The best examples of twentieth-century instrumental popular music often land in historical limbo. They’re not jazz, and they’re no longer popular, but they are music. What can we listen for now?

A Brief Tour of “Two Kinds of Music”

“There are only two kinds of music: good music, and the other kind.”

People usually credit Duke Ellington with this phrase, or some variation of it, without specifying where or when he said it. We also don’t typically include the exact section of Genesis for “Am I my brother’s keeper?” or Star Trek II for “the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few.” A citation can seem pedantic in its redundancy.

I’m a member of a small group: people who have been told they like “the other kind” of music and care why it’s not “good.” I often wonder what Ellington meant by this statement. So, I got pedantic and tried to find a citation.

Sources

The best connection to a literary source I could find was by Alex Ross, who cites Ellington’s article “Where is Jazz Going?” from the March 1962 issue of the Musical Journal.

In that piece, Ellington reflects on the “future of jazz.” He considers whether musicians with “a background of educational equipment that is way out ahead” of earlier jazz musicians will affect the music’s folk roots. Ellington highlights the need to grow a supportive audience. He describes being told his music isn’t sufficiently Black and why rock and roll is the most “raucous form of jazz.”

The piece is worth reading in full, but I was looking for this passage:

“As you may know, I have always been against any attempt to categorize or pigeonhole music, so I won’t attempt to say whether the music of the future will be jazz or not jazz, whether it will merge or not merge with classical music.

There are simply two kinds of music, good music and the other kind. Classical writers may venture into classical territory, but the only yardstick by which the result should be judged is simply that of how it sounds. If it sounds good, it’s successful; if it doesn’t, it has failed. As long as the writing and playing are honest, whether it’s done according to Hoyle or not, if a musician has an idea, let him write it down.

And let’s not worry about whether the result is jazz or this or that type of performance. Let’s just say that what we’re all trying to create, in one way or another, is music.”

Ellington was not simply stating that jazz and classical music were equally worthwhile; listening to both can demonstrate that. He sounds interested in expanding appreciation for a broader range of music. He ends this passage and his piece with a summary rejection of labels.

At the same time, Ellington witnessed the classical/jazz binary at work since the start of his career. He flanks his soon-to-be-famous words with comments on classical music, highlighting his skepticism of musical hierarchies. As one commenter points out, Ellington was aware of shifts in popular music and diminishing opportunities for musicians in his specific branch of “good music,” so there might also have been a subtle but pointed commentary on “the other kind” of music selling out venues.

Ross goes on to mention an earlier source for this idea, one well outside of jazz, American popular music, or the twentieth century. In the following passage from his 1863 book Social Life in Munich, English jurist and writer Edward Wilberforce attributes the quote to Italian opera composer Rossini (1792–1868):

“Rossini’s saying about music applies to painting. Rossini is supposed to have said to some learned gentleman who was entertaining him with a discourse on nationalities in music, ‘My dear sir, there is no such distinction as you suppose between Italian, French, and German music; there are only two kinds of music, good and bad.’”

Rossini was interested in geographic boundaries applied to music. Critics dismissed his works as frothy, florid stuff best suited for Italian audiences. Some described Rossini’s music as too “German” in its scoring. While Ellington is disputing hierarchies, Rossini is sweeping aside borders.

Both composers encountered criticism about the cultural authenticity of their music and its accessibility. Despite being separated by an ocean and a century, and though they arrived along slightly different paths, both reached similar conclusions. They also avoid describing “the other kind” of music. Ellington won’t even use the word “bad.” Maybe he was having fun with implications. Perhaps he didn’t like such a drastic label. Either way, Rossini had no such issue.

As for who said it first or where they might have heard it, Ross says that “the real source” of this quote is probably Franz Grillparzer, an influential Austrian playwright. The relevant text appears in the 1856 poem “An die Kritiker.” Here is Ross’s translation from German:

To the Critics

The critics, meaning the new ones,

I compare to parrots,

Who have three or four words

That they repeat in every place.

Romantic, classical, and modern

Seems a judgment to these gentlemen,

And with proud courage they overlook

The real genres: bad and good.

It’s unclear if Grillparzer is discussing drama, music, or the arts in general. “Romantic, classical, and modern” can mean both eras and styles. But the quote still resonates. Here, it’s just one part of a larger assault on critics—not just on an idea, but people! Grillparzer is more upset by their overuse of musical labels than by the existence of those labels. “Good and bad music” is the knockout punch in a bigger fight.

Uses

At this point, the chain of authorial custody became less interesting than the usage. A quick search of different online resources revealed hundreds of quotations, misattributions, and possible plagiarisms—though, again, we rarely hear a source for “do unto others, etc.”

For example, this writer for the Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald of July 20, 1865, could be accused of plagiarizing Rossini, referring to common wisdom, or even relying on what might have already become a cliché:

“[Conductor] Luigi Arditi is unlike most maestri, for he has neither prejudice nor partiality: He only recognizes two kinds of music: good and bad. German, French, Italian, or English, is alike to him, so that it be only first rate.”

The Bath Chronicle of March 8, 1888, was over-generous in its attribution, suggesting collaborative authorship:

“Rossini once told [French opera composer] Gounod that he only knew two kinds of music, good and bad, and Gounod himself says, ‘I dislike all this nonsense about German music, Italian music, French music, and so on: geographical boundaries cannot hedge in harmony.’”

Nearly 60 years later, Metronome writer Arthur McAuliffe (in his “A Treatise on Moldy Figs” from August 1945) retrofits the wisdom by substituting jazz styles for European schools:

“The truth surely is that Metronome judges everything on its individual merits and has only two kinds of music in mind—good and bad—instead of making arbitrary divisions into New Orleans, Chicago, etc. or jazz and swing.”

Jazz lovers may have been splitting those hairs. For classical snobs, “good music” and “bad music” were practically synonyms for “the music of an elite group of primarily Western European composers performed in concert settings and not marketed for mass consumption” and “the other kind,” respectively.

Ellington took on the longstanding “debate” in his piece. In “Meredith Wilson Takes This Stand” (Band Leaders and Record Review, April 1947), the writer uses the quote for more direct criticism of the classical community for looking down on jazz. Composer and bandleader Victor Herbert was fighting these hierarchies decades earlier from other spaces in American popular music. He includes the quote in a few articles, but this interview from the Cincinnati Enquirer on January 6, 1918, is representative of his views:

“When you really analyze music, there are only two kinds: good music and bad music. The mere fact that a certain composition is the work of one of the classicists, or that it is written in the classic style, does not necessarily make it a fine, good work. Nor does it follow that all light opera music is trashy. On the contrary, it is just as artistically important to have good light music as it is to have good music in the larger format.”

As late as 2000, Ray Charles (per Bill Milkowski, “Midnight and Steve Turre,” JazzTimes, October 2000) used the quote to argue that classical music doesn’t get to be grandfathered in as “good music”:

“Duke Ellington once said that there are only two kinds of music: good and bad. And it’s the truth! Because you can find beautiful, good music in every branch of music. And don’t let nobody fool you when they say, ‘All classical music is good.’ That’s a lie, ’cause it ain’t. Just ’cause it’s classical, that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s good.”

Ellington’s quote can become an invitation to seek out new sounds or a subtle dig at listeners who prefer chaff to wheat. Gene Lees, in his Jazzletter of January 1982, mentions “a remark attributed variously to Duke Ellington, Claude Debussy, and Richard Strauss that holds that ‘there are only two kinds of music: good and bad.’” He then expands on the quote:

“But try to ‘prove’ that a certain piece is good or (which is harder) that another is bad. Good or bad intonation, good or bad harmonic motion and voice leading, economy of means and its opposite, all the things by which refined judgment of music is made, mean nothing to someone whose experience has not prepared him or her to notice them. Lalo Schifrin has referred to most contemporary pop composers as ‘diatonic cripples,’ and Clare Fischer, on the same subject, describes ours as an age of ‘harmonic regression.’ They are both right. They are both irrelevant to someone jiving down the street with a Walkman mainlining moronic music into his brain.

For a similar repurposing in an academic setting, there’s William M. Lamers’s article, “The Two Kinds of Music” (Music Educators Journal, 1960). Lamers was the assistant superintendent for the Milwaukee public school system. Note the “Newton’s apple” origin for the quote:

“Long ago, I was struck with the fact that there seem to be two kinds of music: ‘Great’ music, ‘good’ music—to say ‘the classics’ would not be quite accurate—the music we teach in our schools. (2) ‘popular’ music, which we eschew in our school programs as something inferior. Apart from the schools, 16 years ago, in most places, most of the time, ‘popular’ music of a rather low order was the music most Americans lived by. It crowded better music off radio and television. It blared in barber shops and stores. It was what people sang, what the young people in our schools delighted in when they escaped from the control of the school. We seemed then to suffer from a nemesis of less than mediocrity. And for the life of me, I don’t find much change from that pattern today.”

Lamers’s subsequent guidance for his colleagues shows he was a staunch advocate for music education and musical refinement outside the classroom. Alongside his advice to fellow teachers, his suggestions for the larger community include complaining about the music being played inside local businesses and organizing students “in a crusade against musical trash.” To Lamers, musical trash is easy to hear—though he also warns fellow educators to “watch your own [musical] tastes.”

These arguments enlist the quote to reinforce musical hierarchies. It would be excessive to paste it here, but Allan Bloom devoted an entire chapter of his 1987 book The Closing of the American Mind to that end.

On the other hand, for Alonzo Levister (“What is This Thing Called Jazz,” Jazz World, March 1957), the quote is a call to pride in one’s subjective tastes:

“There are, fundamentally, only two kinds of music—good and bad. If it moves you, it’s good. If not, it’s bad.”

Louis Armstrong never seemed embarrassed by what anyone thought was “good.” He had big ears and a drive to bring his music to new and wider audiences. Armstrong scholar Ricky Riccardi explains that Armstrong actually credited the quote to trombonist Jack Teagarden, but because Armstrong almost always quoted Teagarden, people attributed it to Armstrong! He would also occasionally use it without mentioning Teagarden. I haven’t found the interview, but Phillip D. Atteberry (in “A Century of Satchmo,” The Mississippi Rag, April 2001) mentions one such exchange with Edward R. Murrow.

Trummy Young and Kid Ory were both trombonists who played with Armstrong. Young recalled Ory “once telling a San Francisco reporter that ‘there is [sic] only two kinds of music: good and bad.'” Young took the quote as a source of didactic inspiration. To him, it meant that “aspiring musicians should ‘listen to all good music and try to work out their own style. Learn as much as possible and practice for good technique'” (from Charles E. Martin, “Trummy Young: An Unfinished Story,” The Second Line, Summer 1978).

Here are a few more attributions from the jazz pantheon:

“Current Biography reported as far back as 1944 that Eddie Condon scoffed at the concept of ‘Chicago-style’ musicians, saying, ‘There are only two kinds of music: good and bad.’ (I’ve also heard that line attributed to other musicians at one time or another, but Condon is on record as having said it a half century ago.)

—Chip Deffaa, “Discusses Eddie Condon: Town Hall Volume 9,” Jazzbeat, Fall 1993”

“I never liked the idea of categorizing music, though. I think Kenny Clarke was right when he said that there are only two kinds of music: good or bad. But I think the industry and consumers need guidance, or help, with jazz music.”

—Peter Schmidlin quoted in David Zych, “Label Watch: TCB,” JazzTimes, December 1997

“For instance, the great ragtime player-composer Eubie Blake, a close friend of [Max Morath]. ‘Eubie said there are only two kinds of music,’ says Max. ‘Good…and bad.’”

—review of The Road to Ragtime in Jazzbeat, Winter–Spring 2000

When Woody Herman passed away in 1987, several articles included the quote, starting a game of “jazz wisdom telephone.” Two days after Herman’s death, an obituary in The Miami Herald on October 31, 1987, quoted him citing Duke Ellington and Igor Stravinsky. An obituary for Herman in the Star Ledger of Newark, New Jersey, on November 2, 1987, included the following:

“For Woody Herman, at all times in a durable and incandescent career, there were only two kinds of music: ‘good and bad.’”

A letter to the editor in the Los Angeles Times published on November 15, 1987, said that the writer “recently heard” the quote from Woody Herman. Numerous articles used some version of the quote in pieces on Herman.

Naturally, the quote spoke to a wide range of artists. Here’s Noel Redding (in an interview with him and the rest of Jimi Hendrix’s band published in Jazz & Pop, July 1968) adapting it to Woodstock parlance:

“There are only two kinds of music—good and bad—regardless of what you play or what sort of bag you might be in.”

A profile of country artist Reba McEntire published in multiple publications during 1987 quotes her as saying, “Don’t categorize me or my music. There’s only two kinds of music to me: good and bad.” Between Herman’s passing and McEntire’s scolding, 1987 was a banner year for the quote; mentions of it spiked across the United States.

Kiss co-founder Paul Stanley also used it in an interview published in several newspapers during March 2021. Blues musician and scholar Kat Danser (in a profile by journalist Paul Tessier for The Morning Star of Vernon, British Columbia, on March 15, 2019) said that “when you go down south, everybody says, ‘There’s only two kinds of music: good music and bad music. Danser varies the meaning here slightly, chalking the phrase up to a regional insight.

Substitutions

At different points, speakers swapped in other categories for “good music,” “the other kind,” and “bad music.” Not all of them were intentional, and they probably illustrate the speaker’s individual priorities more than their musical philosophy. For example, in a letter to the Cornish Guardian of February 21, 1908, one correspondent declared, “There are only two kinds of music: sacred and silly,” explaining that “everything good in the world is sacred,” taking rarefied taste into spiritual territory.

The erudite, caustic journalist H.L. Mencken was likely familiar with the quote through some classical attribution. In a letter dated March 6, 1925, he wrote that “There are only two types of music: German music and bad music.” Mencken was not being ironic. He genuinely believed in the superiority of his native culture. Sometimes musical taste is about much more than music.

Let’s end with maybe the broadest, most down-to-earth, and humblest variation, by a young artist finding his way. Ornette Coleman was likely familiar with the quote, probably through Ellington, so it’s easy to imagine this as a riff on Ellington’s wisdom:

“I think when I was coming up (starting) to participate in instrumental music, I hadn’t really thought about the problem of what instrument, what kind of music or what. I just thought that since there were only two kinds of music, vocal and instrumental music, there would be enough space left for me to participate in instrumental music.”

—Ornette Coleman, “What Do You Play After You Play the Melody? John Litweiler Talks to Ornette Coleman,” Disc’ribe, Fall 1982.

His modesty is incredible: Imagine Ornette Coleman wondering if there’s room for him!

There’s much more to “good and bad music,” but at this point, who said it is first far less interesting than why so many people keep saying it. I still don’t know which bucket my musical tastes fall into. Most of the speakers don’t spend a lot of time explaining “the other kind” of music, which reminds me of another piece of often unsourced wisdom:

“If you don’t have anything nice to say, don’t say anything at all.”

Thanks

Many thanks to Ricky Riccardi and Michael Steinman for finding material and sharing their thoughts on this topic. Also, thanks to anyone reading this and some of the more abstract posts I’ve been sharing recently.

Now Also on Substack

Going forward, I will cross-publish here on WordPress and on Substack. If you’re reading this and want to keep reading, you don’t need to do anything. But if you prefer, you can now also read my posts at Substack. Just click the pile of papers below to subscribe there.

Also, thank you so much for reading!

South African Ballroom Jazz

Here’s an unusual find (for me) from browsing used record shops during a vacation: a 78-rpm recording on a South African label featuring a widely known band from that country:

I’m unable to precisely date this record. Gallotone Singer was a label from the Gallo (Africa) Ltd. company, operating out of Johannesburg, and in use by at least the mid-30s. Sonny’s Jazz Revelers was also active around the same time. Directed by saxophonist Sonny Groenewald, the group originated in Cape Town and toured the country, playing a blend of jazz and their hometown’s dance music.

Sources I’ve read classify Sonny’s Jazz Revelers as part of the langarm tradition, a South African ballroom dance style and social gathering popular among Black communities. Langarm developed out of vernacular dances with a pronounced influence from American jazz. The saxophone is vital to the music and setting, often played with a prominent nasal tone and vibrato.

On this record, instead, the two-saxophone lead plays with a rich, bright sound and varying degrees of collective improvisation. The pianist receives a good share of solo space. Their dialoging phrases and ringing syncopations add to the overall light spirit and heavily accented rhythm.

The Revelers also trot through beloved jazz standards from the twenties. The repertoire, combined with the double saxophones and earnest melody choruses, reminded me of dance bands from that era: a warm, rhythmic throwback. An astute musician-friend compared it to a mid-twenties dinner club band—if they got to record electrically!

I’m unsure how a South African record ended up in a record store bin in the mountains of New England, but it was mine for two dollars. I hope you enjoy it. Please note that all of the above is a broad summary of cursory research. Further information and corrections are welcome.

Garvin Bushell’s Time (Signature) Travels

Reed player Garvin Bushell began his career accompanying vocalists in the early 20s:

He played with some of the greatest names in jazz, even providing some of the earliest recorded examples of jazz bassoon:

Bushell moved on to playing lead alto for Cab Calloway and Chick Webb during the swing era:

He was still playing during the so-called “Dixieland revival”:

But he also performed with ultra-moderns like John Coltrane and Eric Dolphy:

Bushell heard and played a lot of music. His autobiography was bound to have great stories and insights into jazz history. But he was just as fascinating when it came to describing the sound of jazz across six decades: regional styles, different approaches to blues, the links and distinctions between ragtime and jazz, musical cross-pollination between cultures, and more.

His references to two- and four-beat styles in early jazz are especially intriguing. This is a popular topic among historians and musicians. It’s safe to say that the recollections of an ear witness published in 1988 are now part of the discourse. But even on their own, Bushell’s comments remain an insightful travelogue and a peek into unexplored routes in jazz history.

Rhythms and Regions

Bushell’s autobiography, Jazz from the Beginning, was first published in 1988 with a revised edition in 1998. It expands on (and corrects) a lot of material from an article published in three parts for The Jazz Review in 1959, “Garvin Bushell and New York Jazz in the 1920s.” Nat Hentoff gets the byline, but it’s mostly Bushell’s words. It’s telling that Bushell’s autobiography incorporates a large chunk of a regional exploration. Geography is a significant part of his musical accounts as well as his personal journey. He traveled extensively, starting when he was barely into his teens, amidst a lot of exciting changes in American popular music.

Bushell first left his hometown of Springfield, Ohio, in 1916 as part of a traveling circus band. The group played in Florida and “parts of the South” as well as Indiana, Illinois, and Kentucky. The music, as well as the experience, left a deep impression. Decades later, alongside remembrances of long hours and lowered standards of hygiene, he recalled the circus band’s repertoire and rhythmic feel:

“…we’d ride on a wagon for the parade and play ‘Beale Street Blues’ or ‘The Memphis Blues’ or ‘The Entertainer’ in fast tempo, or else some old military marches. Other bands played them two to the bar, [but] we’d play them four to the bar.”

Bushell’s bandmates were from Florida, Georgia, and Tennessee, but he grew up hearing bands play in four. He points out that “the jazz bands, however, that I’d heard in Springfield or had heard about [e.g., Freddie Keppard’s Original Creole Orchestra from New Orleans] played in four.” He also notes that among early vaudeville musicians, circa 1920–21, “everybody played four beats.”

Bushell associated the “‘two’ tempo” with ragtime and four with jazz, going back to his earliest music lessons:

“Ragtime, as it was called then, had the technical essence that was later required in jazz. While ragtime was always played in a moderate or fast ‘two’ tempo, jazz merely slowed it down to a fast or medium ‘four.’ Most of all, the old rags had a melodic pattern. Therefore, I began to study rags on piano and omit the melodic pattern, just improvising on the harmonic pattern.”

When Bushell moved to New York City in 1919, he heard that “Negro dance bands in New York played fox trot rhythm and still adhered to the two-beat rhythmic feel.” He does mention “dance bands” here, as opposed to the “jazz bands” he heard playing in four. While the two terms were often interchangeable in American popular music after World War I, Bushell’s usage seems intentional.

In the same passage, he singles out Tony Sbarbro, drummer for the ODJB, as “about the only jazz [emphasis mine] player I heard doing it in two.” Bushell is writing about jazz going back to years before the ODJB released what many consider the first jazz record. Harsh critics depict two-beat jazz as already outdated by the middle of the twenties. Maybe some listeners accustomed to jazz in four heard what the ODJB was doing in the late teens and thought they were rebels!

Who Played How, Where, and When?

Later commentators usually discuss the comparatively looser four-beat feel as a Southern influence during jazz’s development. Some narratives treat the two-beat style as a relic of an archaic eastern style supplanted by the migration of Southern musicians, especially New Orleanians in Chicago. It can seem like the twenties started in two and ended in four. But one of the earliest working jazz musicians tells us that, by the start of the decade, playing in two was rare.

Most of Bushell’s colleagues in the circus band were from lower Southern states. Ohio is a smaller midwestern state that borders two Southern states, so the shared rhythmic approach may not be surprising. Vaudeville, on the other hand, was a popular nationwide entertainment by the turn of the century. Bushell tells us that most, if not all, of the musicians on the circuits played in four. That indicates an early and widespread adoption, suggesting perhaps that:

- The majority of vaudeville musicians were of Southern or Southern-adjacent origin.

- Southern musicians were already a well-established influence.

- Different musical communities across the country shared parallel tendencies.

- Professional musicians in this part of the industry were developing common repertoire and musical practices.

- It was all mere coincidence.

Jazz scholars can offer better hypotheses. I’m comfortable ruling out essentialist explanations. Bushell’s remarks remind us that there were multiple musical communities reflecting a range of cultural and musical identities. Saxophonist, composer, and music historian Allen Lowe often discusses the excitingly messy, non-linear path of American music and how Black culture in particular was not a monolith. Regions, class, and many other distinctions shaped different perspectives and aesthetics, even as individuals, communities, and styles bridged and influenced each other.

In New York City, for example, musicians born there or who “had been in the city so long they were fully acclimated” were, by Bushell’s account, trying to forget Southern traditions, including playing blues and other “low element” music.” Nonetheless, Bushell still talks about jazz bands in the Big Apple, groups who “improvised in the cabarets” with “a different timbre from the big dance [emphasis mine] bands.”

He describes a distinct form of jazz that “leaned to ragtime conception—a lot of notes” without a blues sensibility. “There wasn’t an Eastern performer who could really play the blues,” admits Bushell. “We later absorbed it from the Southern musicians we heard, but it wasn’t original with us.”

This vestigial branch of the jazz history tree is not as well-documented as other styles. By 1922, Bushell says he and fellow eastern musicians “were certainly influenced by New Orleans jazz.” Southern musicians, for example, from Louisiana and Texas, were also influencing players in the Midwest. That means he was a witness to a brief but fascinating and often unexplored chapter in jazz history.

Musician, Witness, and Historian

Of course, these are excerpts from a single musician’s observations made decades later. Bushell also makes a lot of associations about parts of the U.S. regarding how musicians played (as well as some comments about how well they played it). Like most generalizations, attributing a particular musical style to a specific region can get tricky.

But this is what Bushell heard, and he was far from an ordinary witness. He was also able to recall and document what he heard, which isn’t always a given. I’m not a creative or a psychologist, so I won’t analyze professional musicians. But I believe that deeply rooted practices don’t always lend themselves to self-conscious analysis or precise linguistic description. Most musicians were probably too busy playing music to take notes on music history. They were participants, not chroniclers. This is not a criticism. Bushell doubled as history maker and chronicler as well as obbligato clarinet, lead alto, bassoonist, and whatever else the music demanded.

Here’s six minutes of Bushell’s smart, vivid spoken soundography:

Funny Accents and Faux Jazz

I didn’t worry about my regional accent until I got to college. My speech didn’t change when I got there, but for the first time, I met people who commented on my speech. They never insulted me, but for the first time, I wondered if I “talked weird” or “didn’t speak properly.”

One professor enjoyed repeating certain words I used when answering questions in class, playfully drawing attention to my accent while demonstrating the proper pronunciation. They didn’t correct me on names or jargon. They’d just find some unremarkable word amusingly incorrect. If I dropped an “r,” they’d lodge it back into place. If I slurred a fricative, they’d over-enunciate it (e.g., “THose THings, Andrew?”). They especially liked to sharpen my softened “t’s” (“Yes, in the capiTal…”).

My Spanish professor was more diplomatic. When my regional accent came out—for example, asking “day don-day err-ess” and not “¿de dónde eres?” or accenting the wrong half of “hablo”—they would offer corrections in a neutral tone. They also politely addressed some of the pronunciations I picked up from Puerto Rican and Dominican friends back home. My Italian professor was not as generous when an occasional Sicilian pronunciation slipped into my answers. I grew up hearing some phrases from neighbors. I thought of them as just another way to speak Italian, but this Milanese-born speaker literally didn’t want to hear it.

In their own way, all three teachers were telling me “that’s not the way it should sound.” They were teaching me that proper pronunciation, inflection, and rhythm were just as important as vocabulary and grammar. Without the right sounds, I might be saying something but not speaking the language.

For my Spanish teacher, it was a practical matter. The correct sound allowed students to communicate effectively within that linguistic idiom. My Italian teacher was concerned with authenticity. For them, variations obscured the more refined usage. “People may speak any way they choose, but they’re not speaking Italian.”

My amateur elocution coach’s suggestions didn’t make the same impact. Beyond the fact that they were teaching a political science course and not an English seminar, their guidance pointed toward social convention rather than linguistic precision or cultural pride. It felt like a stylistic preference rather than a claim about cultural authenticity. They objected to how I said what they clearly understood.

“That’s not the way it should sound” could also be a statement of elementary music criticism. The notes, the pitches and rhythms may be correct. But if elements like timbre, articulation, phrasing, or dynamics are off, the music might “sound funny” enough to fall short of some aesthetic threshold. It’s something more than a local derivative or creative choice. Depending on the listener, missing the mark might mean more than disliking the music; they may hear a crass imitation, dilution, or an insult to that tradition and its community.

These distinctions often appear in discussions of all the pre-, para-, and formerly-known-as-jazz recorded during the twenties. Ironically, Jazz Age listeners consumed a lot of music that, today, wouldn’t earn the name even by the loosest standards. A century ago, “jazz” was as much a marketing term as a musical description. It’s now easy to dismiss a lot of this music based on anything even approaching jazz content (which too often leads listeners to dismiss it as music entirely). Yet the twenties also produced a lot of music audibly influenced by what is now commonly accepted as authentic jazz of the time.

Take Joseph Samuels’s “Bugle Call Rag.” The tune is one of the earliest jazz standards. It’s received hundreds of hot treatments, starting from its inaugural recording by the New Orleans Rhythm Kings (two of whose members composed the tune), less than a year before Samuels and his band recorded it in May 1923.

At the time, New Orleans-style jazz (or New Orleans via Chicago-style jazz) was growing in popularity and influence to become the dominant style of jazz. It is an obvious influence in terms of repertoire and instrumentation in Samuels’s “Bugle.” The musicians don’t sound hesitant within these influences. They’re not struggling to play together or maintain musical momentum. Still, in terms of rhythm, inflection, and emotional impact, Samuels’s record may subvert contemporary expectations about what “jazz” was supposed to sound like:

Beyond flatted notes or bent tones, there’s not much of a blues sensibility here. That might be a summary judgment against this record being “jazz.” There are shades of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band without the intense, sometimes manic energy found on their records. The Samuels group is far from the earthy, seamless polyphony of King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band. Musicologists often discuss jazz musicians doing things “between the beats.” This band thrives on the beat—specifically up-beats and off-beats. Their syncopation is deliberate and intense. Their eighth notes are confidently symmetrical.