A profile of the Ipana Troubadours in Radio Broadcast magazine singles out just one sideman in the band. Even among musicians that leader Sam Lanin “picked from the country’s best dance and symphony orchestras,” he receives special attention:

Lucien Schmit, for instance, virtuoso cellist, was Walter Damrosch‘s first cellist for five seasons and is also an accomplished pianist and saxophone player. Schmit is a representative member of the group.

A photo of the Troubadours shows an unidentified player holding a cello with a saxophone at his feet. Section mates on either side of him hold their saxophones. But the cellist’s sax doesn’t even get a stand; it rests directly on the floor. If the reader didn’t know any better, they might assume that sax was just an occasional double.

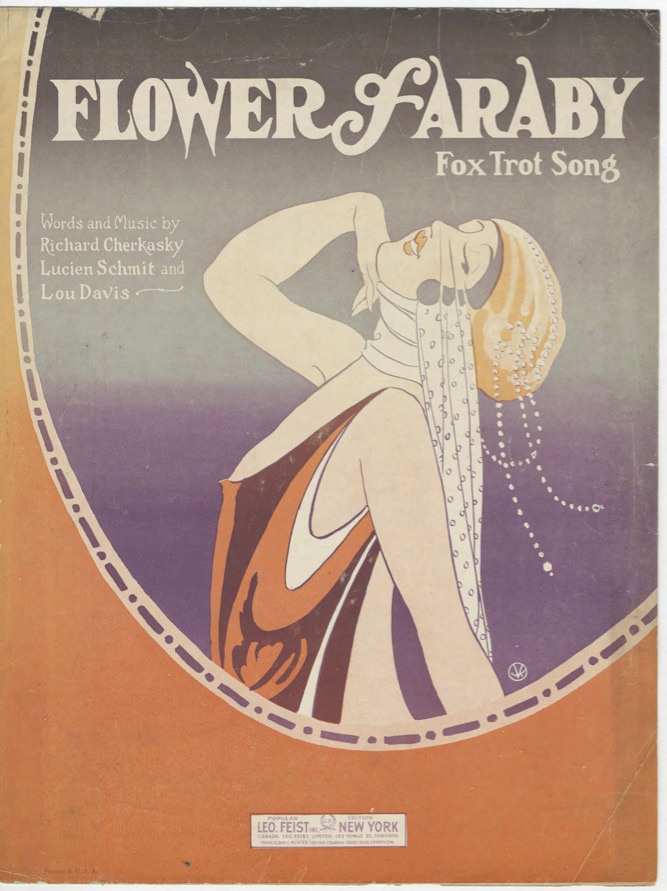

Of course, “Lucien Schmit” sounds like “Lucien Smith,” a name record collectors and hot dance aficionados likely recognize as one of the saxophonists on several recordings by Lanin and other bandleaders. It’s found next to more well-known names like Bennie Krueger, Miff Mole, Red Nichols, Harry Reser, and the Dorsey brothers in many discographies.

A 1931 radio listing makes the connection more explicit, but even the copywriter faces an identity problem with his subject:

Many performers know how to double in brass, but Lucien Smith will demonstrate the talent which permits him to triple in brass and strings. He will appear as soloist on piano, cello, and saxophone. Best known as a master of the cello, Mr. Schmit has won the praise of music critics for years…it was [conductor Eugene] Ormandy‘s idea to present him in the three phases of his artistic accomplishment.

Mistaking the saxophone as a member of the brass instrument family may be mere carelessness. But the switch between “Smith” and “Schmit” suggests which artistic phases are more or less important. Smith may play many instruments, but Schmit is the cello master earning critical praise.

In contemporary reports, saxophonist “Lucien Smith” didn’t get much attention. With just a couple of exceptions, that name is limited to discographies. For the sake of argument (and according to far more knowledgeable researchers than this writer), it’s safe to assume they were the same musician. And some cursory research shows he enjoyed a long and varied musical career spanning different instruments, repertoires, and artists.

Prodigy

Government records indicate that Lucien Alexander Schmit was born in Belgium on January 6 of either 1898 or 1899 (depending on which draft card). A New York Times obituary from July 22, 1976, fills in the blanks and notes early talent:

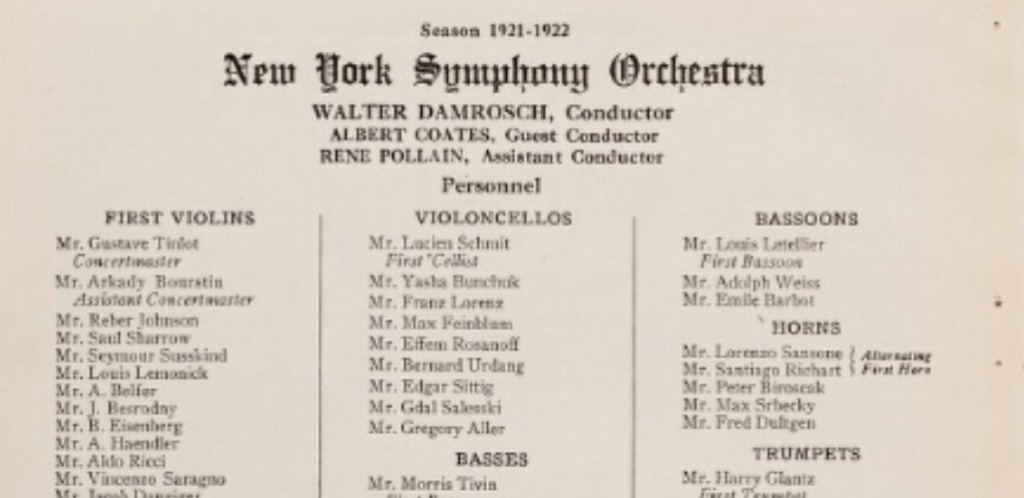

Lucien S. Schmit, a cellist who first performed publicly at the age of seven in Paris and who became a member of the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra at 13…came to this country in 1909. He became first cellist in the New York Symphony Orchestra in 1921 under Walter Damrosch.

Still, there’s a big issue here. And it’s not just the middle initial, which was reprinted as “S” elsewhere. The obituary omits the subject’s many recordings as a reed player with several bands. It even ignores his extensive work as a cellist on recordings with everyone from Quincy Jones to David Sanborn.

This obituary doesn’t mention any ability—let alone talent—for playing saxophone. “Lucien Smith” got left out of the obituary for “Lucien Schmit.”

Symphony Cellist

Across multiple discographies, newspaper articles, radio listings, promotional materials, and other documents, the division between names and roles is surprisingly consistent. “Lucien Smith” plays reed instruments, mainly sax, and “Lucien Schmit” is a cellist. And, based on the amount of historical documentation, the cellist received a lot more press and promotion.

Conductor Walter Damrosch’s pick for principal cello was bound to get plenty of attention. Audiences and critics respected Damrosch for his musical direction, premiering new works, and educational efforts. Damrosch’s New York Symphony was a respected institution later incorporated to form the New York Philharmonic. He remains a well-known name to this day.

Aside from brand recognition, a principal cellist would probably have handled most (if not all) of the solo parts for the orchestra. Several reviews talk about “Lucien Schmit” featured in works such as Saint-Saëns’s Cello Concerto in A Minor and cello pieces by Bach and Boccherini. One New York Times critic praised Schmit as a “graceful and fluent player” in a program of contemporary classical pieces. A writer for Etude magazine, years after hearing Schmit with the Lutèce Trio, recalled that an audience of about 5,000 people “thought him the star performer” despite playing on a mediocre instrument.

Schmit played under Damrosch for five seasons. Half a decade playing to critical acclaim with a renowned orchestra under an esteemed conductor casts a large shadow. At this time, many listeners were more likely to turn their noses up (in public, anyway) to jazz and popular music. Among self-identified “respectable” circles, European art music was the accepted social currency. It was bound to get more press in mainstream publications. It also seems like Lucien Smith, the saxophonist, was rarely featured as a soloist. In short, his dance band legacy might have suffered based on cultural associations and sheer audibility.

On June 30, 1923, Lucien Schmit, cellist, recorded Rubenstein’s Melody in F (mx. 0543) and “The Swans” from Saint-Saëns Carnival of Animals (matrix number 0544). Audio of each side follows. Images and audio from Internet Archive.

Saxophonist

It’s unclear when he began playing saxophone with dance bands. The earliest discographical entry (that the writer could find) for “Lucien Smith,” the reed player with Lanin and others, is a February 1922 session with Bailey’s Lucky Seven for the Gennett label. Smith is listed as playing tenor sax in the probable personnel. Yet at the time, he was still the principal cello under Damrosch. It’s also hard (for this writer) to single out a distinct tenor sax voice on “My Mammy Knows” or to identify the tenor lead “On the ‘Gin, ‘Gin, ‘Ginny Shore.”

His reasons for deciding to play saxophone professionally are beyond this writer’s research or qualifications. He may have wanted to try something new. Maybe the popularity of dance bands seemed financially promising or musically challenging. It was likely some combination of practical and personal reasons. Whatever the cause, saxophonist Lucien Smith doesn’t appear on another dance band date until August 1924.

From that point, he’s on plenty of great hot dance and jazz records! Discography entries that include “Lucien Smith” read like a who’s who of hot dance/jazz bands: Nathan Glantz, Dave Kaplan, Krueger, Lanin, and Ben Selvin are just a few of the names. Tom Lord’s online jazz discography lists Schmit on 85 sessions between 1922 and 1931—and that’s just what made it into the discography as “jazz.” He likely doubled multiple saxophones and clarinet as a working dance band musician. His substantial presence with these bands indicates significant skill, versatility, and reliability.

Despite the obvious talent, the last session listing Lucien Smith on reeds appears to be August 7, 1931, with violinist Billy Artz’s band. Artz and Lucien both played in B.A. Rolfe‘s famous orchestra, where Lucien is listed as doubling clarinet, tenor sax, and cello. The two likely forged a connection there. He may also be the hot tenor sax on “There’s A Time and Place for Everything.” But at this point, maybe regularly playing tenor was unneeded or less lucrative during the Great Depression.

Radio Cellist and More

Instead, cellist “Lucien Schmit”—who happened to also play saxophone and piano—resurfaces in the press and discographies. The New York Times obituary states that “During the 1930s, he was active in radio musical programs…musical director of ‘The Royal Typewriter Hour’ and for 20 years was featured on such programs as ‘The Telephone Hour,’ the Firestone Show, the Longines Symphonette program and ‘The Prudential Family Hour.'” But that obituary is entirely framed around his work as a cellist.

Some contemporary reports of “Lucien Schmit” reference work as a saxophonist and pianist, like this April 24, 1930 radio listing in the Hartford Courant:

Lucien Schmitt [sic], the violincellist of the Melody Moments orchestra and other concert orchestras on the networks, will demonstrate his ability to triple in brass and strings…He will contribute piano, cello, and saxophone solos to the concert.

In directories for the New York American Federation of Musicians, Local 802 (generously provided by Vince Giordano), there’s only “Lucien A. Schmit” listed in the “Cello” section. Whatever else he may have played on the radio, Schmit’s primary role was always as a cellist.

Over the next few decades, in addition to radio work, his cello as well as his violin and viola are listed in studio recordings with Kenny Burrell, Perry Como, Johnny Griffin, Coleman Hawkins, Artie Shaw, and Wes Montgomery, among others. Almost inevitably, it’s “Lucien Schmit” in the string section. Grammy-wining bandleader and hot music historian Vince Giordano explains that pianist Dick Hyman recalls “Lucien” coming to sessions carrying both reed instruments and his cello.

Along the way, he and his wife raised their only child (who went on to a respected career in engineering). Lucien passed away following a stroke on July 20, 1976, in a hospital near his Manhasset, Long Island home.

Musician

Depending on the area of his considerable experience, you might end up reading two different narratives. Almost all the discographies and press clippings that mention the cellist reference Schmidt, Schmit, or Schmitt. Except for very few contemporary articles, Lucien Smith, a saxophonist, is only found in discographies (though the prolific and knowledgeable discographer Javier Soria Laso gets a lot of credit for covering all the bases by referring to “Lucien Smith/Schmitt/Schmidt”).

There may be a better or more straightforward explanation for using different names. And wider research may show that the associations between the names weren’t as cut and dried. Maybe “Smith” was a deliberate alias or just a propagated typo. But just looking at (some) writings, you might think Lucien Smith’s saxophone was a temporary side hustle compared to Lucien Schmit’s cello.

That probably says more about audiences’ and reporters’ perceptions of “serious” and “popular” music during Lucien’s lifetime. His musical career makes for a single interesting story. You’d just better know who to look for.

Sources

- American Federation of Musicians, directories from 1937, 1943, and 1958

- American Dance Bands on Record and Film by Johnson and Shirley

- ARSC Journal, vol. 24, no. 1: “Georges Barrere” by Susan Nelson

- Brunswick Records: A Discography of Recordings, 1916-1931 by Ross Laird

- Buffalo Times on January 16, 1930

- Daily News [New York] on April 7, 1932

- Etude magazine on April 1922

- Florida International University libraries

- Hartford Courant on April 24, 1930

- International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)/Petrucci Music Library

- Journal of the National Medical Association, Vol. 17, No. 4, December 8, 1925

- Tom Lord’s Jazz Discography online

- Music News on December 28, 1923

- The Musical Blue Book of America for 1922

- Nassau Daily Review on August 26, 1931

- Nathan Glantz’ Orchestra as the Tennessee Happy Boys by Javier Soria Laso

- National Academy of Engineering Memorials: “Lucien A. Schmit Jr., 1928-2018”

- New York Philharmonic website

- New York Times articles

- Pittsburgh Press on January 22, 1928

- Portland Press Herald on April 24, 1930

- Radio Broadcast, September 1926

- Recordings of Bennie Krueger’s orchestra for Brunswick and Vocalion by Javier Soria Laso

- Rhythm on Record by Hilton R. Schleman

- Times-Union [Albany] on April 24, 1930

- U.S. census records

- U.S. draft records

Appreciation

Many thanks to Vince Giordano for sharing his recollections, relevant newspaper articles, and 802 directories. Thanks also to Javier Soria Laso for his insights into the subject and meticulous discographies that first connected the names for me. Thank you, Aaron K., for your fine edits. And thanks to “P.C.” on Facebook.