…or at least the blogosphere:

The Pop of Yestercentury

More Hep Than Hip

A FEW GLOWING SECONDS OF GLORY

A writing teacher one told me to avoid using the word “beautiful.” Well, Michael Steinman’s post about Johnny Windhurst and Jack Gardner is simply beautiful.

I try to cover obscure musicians on my blog, but after reading his post I not only want to hear more of Windhurst and Gardner’s music (and I haven’t even listened to the clip yet), I want to know more about the musicians themselves.

It’s also heartwarming to hear about people like Ms. Taylor, who in this context was “just a fan” but is responsible for preserving this music decades after the scholars and critics would have skipped it and written another biography of Miles Davis. The reference to trading tapes is another uplifting reminder of a time before everything was tagged and downloadable, when people shared music, talked about it and perhaps even got to know one another in the process.

We have come so far yet lost so much when it comes to hearing history, but we always have people like Michael Steinman, and as a result “Gypsy,” Johnny, Jack, Archie Semple and so many others. That is beautiful.

When I returned to my apartment in New York, I thought, “I need music in here. Music will help remind me who I am, what I am supposed to be doing, where my path might lead.” Initially I reached for some favorite performances for consolation, then moved over to the crates of homemade audiocassettes — evidence of more than twenty-five years of tape-trading with like-minded souls.

One tape had the notation PRIVATE CHICAGO, and looking at it, I knew that it was the gift of Leonora Taylor, who preferred to be called “Gypsy,” and who had an unusual collection of music. When I asked drummer / scholar Hal Smith about her, he reminded me that she loved the UK clarinetist Archie Semple. Although I don’t recall having much if any Archie to offer her, we traded twenty or thirty cassettes.

PRIVATE CHICAGO had some delightful material recorded (presumably) at the…

View original post 756 more words

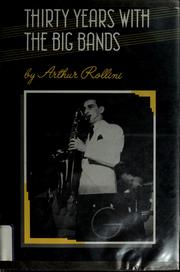

Listen To/With Arthur Rollini

Peer through any “Top Ten Tenors” list and you just won’t find Arthur Rollini. When he’s remembered at all, it’s for his time with Benny Goodman’s epoch-making mid-thirties swing band. Yet as the title of Rollini’s autobiography indicates, he was a skilled enough saxophonist (and apparently devoted yet ultimately disappointed flutist) to make a career of Thirty Years With The Big Bands. Besides Goodman, Rollini played with sweet bandleader (and apparently very crass person) Richard Himber, the exacting, progressive-minded Raymond Scott and on a slew of pickup dates with a variety of jazz legends. Rollini must have done something right.

Peer through any “Top Ten Tenors” list and you just won’t find Arthur Rollini. When he’s remembered at all, it’s for his time with Benny Goodman’s epoch-making mid-thirties swing band. Yet as the title of Rollini’s autobiography indicates, he was a skilled enough saxophonist (and apparently devoted yet ultimately disappointed flutist) to make a career of Thirty Years With The Big Bands. Besides Goodman, Rollini played with sweet bandleader (and apparently very crass person) Richard Himber, the exacting, progressive-minded Raymond Scott and on a slew of pickup dates with a variety of jazz legends. Rollini must have done something right.

Rollini also had big ears to match that big talent. Alongside stories about life on the road, romantic boondoggles and references to “thoughtless…fickle…inconsiderate, etc. Benny [Goodman]!” his memoir is a who’s-who of pre-war talent. Far from name-dropping or even scattered recollection, Rollini effectually offers a listening guide to some now-forgotten musicians, artists who may not have all been innovators but were on bandstands and in recording studios making the music.

Here is Rollini’s extensive list of favorites, excerpted from his book in their order of appearance (emphases mine):

…Irving (Babe) Russin, who played fine tenor sax…Mario Lorenzi, also a good jazz harpist…Fred Elizalde, who was only twenty-three years old himself, a Cambridge graduate who played fantastic piano and arranged brilliantly…Bobby Davis, first alto sax…had a beautiful tonal quality on alto and baritone sax…Matty Malneck, a fine violin player (both concert and jazz)…

…Irving (Babe) Russin, who played fine tenor sax…Mario Lorenzi, also a good jazz harpist…Fred Elizalde, who was only twenty-three years old himself, a Cambridge graduate who played fantastic piano and arranged brilliantly…Bobby Davis, first alto sax…had a beautiful tonal quality on alto and baritone sax…Matty Malneck, a fine violin player (both concert and jazz)…

…Hymie Schertzer was now playing first alto sax [in Benny Goodman’s band]. Bill DePew was on the other alto sax, and Dick Clark and I were on tenors. It was a good sax section!…To this day Ziggy Elman had the most powerful sound that I have ever heard…Harry James was a genius. He could read all of the highly syncopated charts at sight, and he played fantastic jazz solos, different every time…also a good conductor and a fine arranger…Babe Russin, a great tenor man…no match for Vido [Musso]’s strong tone but made up for it with his keen ear and great drive…a good reader and read off all the charts at sight…Murray McEachern…a great talent…I must state emphatically, though, that the 1937-38 [Goodman] band was the best! Apart from Hymie Shertzer, who could swing a great lead alto sax, this band consisted entirely of jazz soloists of great talent…

…Hank D’Amico…was one man who did not try to imitate Goodman. He had a distinctive style of his own, and, as they now say, ears. He could read and transpose almost anything…Joe [Viola] was a schooled clarinet player and an excellent sax man…Ralph Muzillo…with an extremely strong sound and drive, was on first trumpet…Sid Stoneburn, a good clarinet player…Al Gallodoro, in my estimation the best technician of our day…could read and transpose almost anything; he was a self-taught musician and would often practice six or eight hours a day. He could double tongue, triple tongue on alto with ease and was magnificent…Abe [Osser] had absolute pitch…such a keen ear that he could detect a wrong passing note by one of the obscure violinists and could out the right one…Phil Napoleon, the fine Dixieland trumpeter…Johnny Bruno, a fine jazz accordion player…

…To this day, I think that Benny Goodman was still the greatest all-around clarinet player…a creator and influenced many players of his instrument throughout the world. I’ll have to give the number two spot to Artie Shaw, who was so great. The rest are up for grabs: Johnny Mince, Tony Scott, Peanuts Hucko, Barney Bigard, Pete Fountain, Abe Most, Buddy DeFranco, Gus Bivona, Hank D’Amico, Phil Bodner, Walter Levinsky, Mahlon Clark, Matty Matlock, Joe Dixon, Woody Herman, Clarence Hutchenrider, Sol Yaged, Bob Wilber, Buster Bailey, Marshall Royal, Joe Viola, Artie Baker, Paul Ricci, Tony Parenti, Jimmy Lytell, Sal Pace, Pete Pumiglio, Sal Franzella, Drew Page, Izzy Friedman and newcomer Dick Johnson…

Don’t forget Arthur Rollini! I’m willing to assume he knew his stuff and look forward to (re)hearing all of these musicians.

My Find, Your Jukebox: Rare Midwestern Hot Dance Bands On Arcadia

I rarely upload entire albums but given the rarity of this music, its energy as well as its originality and the likelihood that the label is no longer in business (and that most if not all of the musicians are past collecting royalties), sharing this LP shouldn’t hurt anyone.

I rarely upload entire albums but given the rarity of this music, its energy as well as its originality and the likelihood that the label is no longer in business (and that most if not all of the musicians are past collecting royalties), sharing this LP shouldn’t hurt anyone.

In fact this music can’t help but raise the room temperature even as it introduces some mysteries: who were these red hot, all White, syncopated dance bands of the Midwest, taking jazz from Chicago, New Orleans and New York and making it completely their own? Musical breeds from the big three cities are there but these bands’ beat as well as their balance between improvised and arranged material is its own animal.

A few highlights include the slashing, Red Nichols-inspired trumpeter on “Hot Lips,” the clarinet lead throughout “Hot Licks,” the dueling brass and clarinet trios on “Igloo Stomp” and the warm, date night atmosphere of “Leven-thirty Saturday Night.” Play that last one alongside Fess Williams’s recording of the same tune for an illustration of why music can be completely individual even without improvisation.

A few highlights include the slashing, Red Nichols-inspired trumpeter on “Hot Lips,” the clarinet lead throughout “Hot Licks,” the dueling brass and clarinet trios on “Igloo Stomp” and the warm, date night atmosphere of “Leven-thirty Saturday Night.” Play that last one alongside Fess Williams’s recording of the same tune for an illustration of why music can be completely individual even without improvisation.

Please enjoy! Thanks to Electric Buddhas of Portland, ME for keeping this one in its bins. If you are having trouble listening to the above clips, just click on each title below.

1. “Hot Lips” — HENRY LANGE AND HIS ORCHESTRA

2. “Nobody’s Sweetheart” — CLARIE HULL AND HIS BOYS

3. “Hot Licks (aka That’s A Plenty)” — ORIGINAL ATLANTA FOOTWARMERS

4. “There Ain’t No Sweet Man” — HAL FRAZER AND HIS GEORGIANS

5. “Hot Coffee” — RUBY GREEN AND HIS MANHATTAN MADCAPS

6. “Louisiana Bo Bo” — LEW WEINER’S GOLD AND BLACK ACES

7. “The Merry Widow’s Got A Sweetie Now” — LEW WEINER’S GOLD AND BLACK ACES

8. “Igloo Stomp” — ART PAYNE AND HIS ORCHESTRA

9. “Blue Night” — ART PAYNE AND HIS ORCHESTRA

10. “Let’s Sit And Talk About You” — BOB MCGOWAN AND HIS ORCHESTRA

11. “Don’t Hold Everything” — TOMMY MEYERS AND HIS GANG

12. “Things Look Wonderful Now” — TOMMY MEYERS AND HIS GANG

13. “If You LIke Me I Like You” — DUCKY YOUNTZ AND HIS ORCHESTRA

14. “Eleven Thirty Saturday Night” — DICK COY AND HIS RACKETEERS

15. “Cheer Up” — DEXTER’S PENNSYLVANIANS

16. “What’s The Use” — DEXTER’S PENNSYLVANIANS

The New Orleans Rhythm Kings, Off The Record And About Time!

God knows I’ve wished they would do it, wondered why they hadn’t done it yet and widened my eyes every time I heard they were ready to do it. Those rumors have at last coalesced into a near-certainty, and it turns out good things merely take time (and money).

God knows I’ve wished they would do it, wondered why they hadn’t done it yet and widened my eyes every time I heard they were ready to do it. Those rumors have at last coalesced into a near-certainty, and it turns out good things merely take time (and money).

Off The Record is now fundraising to produce The New Orleans Rhythm Kings: Complete Recordings, 1922-25. The NORK will finally receive the same treatment Off The Record gifted on similar sets for King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band, Bix Beiderbecke’s Wolverines and company’s Cabaret Echoes collection. Doug Benson’s masterful audio restoration and David Sager’s loving yet illuminating liner notes are a natural fit for this seminal, rollicking jazz band, (in this writer’s opinion) the white, Chicago-born analog of Oliver’s ensemble. You can donate here to help make it happen.

Yet chances are that most of the people reading this blog already knew all of that. So why, if you have only a passing interest in twenties jazz or have never even heard of the NORK, should you support this project?

For starters, there’s the combination of joyful music presented in sterling sound and wrapped in historical/musical context that breathes like a smart, friendly explanation rather than a lecture. Anyone can enjoy and learn a lot from Off The Record. You also support an enterprise that is all about the music, what collector and writer Mark Berresford called the “to hell with the sales figures, let’s get people listening to this material!” mantra. Great music in a superior format produced by sincere, knowledgeable people: I don’t usually solicit for money on this blog but I’m happy to make an exception this time.

Plus, I really want to get this set produced and into my stereo. So do it for some faceless blogger.

Here is that link, again. Thanks so much!

Chauncey’s Choices: Jazz Drumming Before The Ride Cymbal

If you can excuse Chauncey Morehouse’s less than subtle bias and treat his examples as pedagogical conveniences rather than stylistic axioms, his mini survey of jazz drumming might prove insightful, even encouraging:

Courtesy of Walt Gifford via the late Joe Boughton through Michael Steinman. Date and periodical unknown but estimated to be from DownBeat circa mid-forties.

There is more room for spontaneity or “feel” in loose small group settings than in “concerted” big bands, or over-rehearsed combos for that matter. Yet the interaction between the drummer and the band in “Dixieland” (what was it like to hear that word as five letters rather than four?) is also a matter of content as well as degree.

Morehouse helped pioneer (on record, anyway) a syncopated style of drumming where drummers punctuate the beat as much as they lay it down, though not necessarily ride it a la Jo Jones or for that matter Art Blakey or Roy Haynes. Dixieland drumming stomps before it swings. As Tom Everett once described, it’s the difference between telling dancers where to put their feet down versus suggesting when to pick up their legs.

Morehouse obviously knew which style he preferred and his comments seem tailored to tick off the mussic generalization copps. Yet decades later and after hundreds of textbook pages making it sound as though bop invented the concept of the drummer as more than a flesh metronome, it’s good to hear someone advocate for this style rather than merely remember it.

Concerto for Clarinet and Dance Orchestra

Buster Bailey ended his long tenure with Fletcher Henderson’s orchestra two years earlier yet plays with the fire of a young freelancer on “Some Of These Days” with Dave Nelson and The King’s Men. Just listen here for Clive Heath’s beautiful restoration of this very rare record.

Bailey shapes a swinging yet otherwise straightforward arrangement with a virtual catalog of obbligatos: tongue-in-cheek seesaw patterns alongside the saxes on the first chorus, low register, low volume counterpoint under Nelson’s vocal and wails behind the full band for the finale. Aside from the leader, Bailey is also the only soloist to get an entire chorus to himself; precious real estate on a three-minute 78!

As Scott Yanow put it, Bailey had a “wicked” sense of humor and sounded as though he were trying to rip his instrument a part. He may not have been as warm as Johnny Dodds or Benny Goodman or as instantly recognizable as Sidney Bechet or William Thornton Blue. Yet Bailey’s sleek, cutting tone is well suited to his rapid-fire improvisations. A classically trained musician with a monster technique, whose colleagues insisted he could have played for a symphony if he were white, Bailey just may have had something to prove. He may have also merely delighted in the scales, arpeggios, intervals and runs that form the foundation of a solid clarinet technique, the same way an expert watchmaker appreciates finely crafted cogs and springs or a painter appreciates the brushstrokes as much as the images of a portrait. The term “technician,” often applied to Bailey, doesn’t necessarily require “cold” before it.

As Scott Yanow put it, Bailey had a “wicked” sense of humor and sounded as though he were trying to rip his instrument a part. He may not have been as warm as Johnny Dodds or Benny Goodman or as instantly recognizable as Sidney Bechet or William Thornton Blue. Yet Bailey’s sleek, cutting tone is well suited to his rapid-fire improvisations. A classically trained musician with a monster technique, whose colleagues insisted he could have played for a symphony if he were white, Bailey just may have had something to prove. He may have also merely delighted in the scales, arpeggios, intervals and runs that form the foundation of a solid clarinet technique, the same way an expert watchmaker appreciates finely crafted cogs and springs or a painter appreciates the brushstrokes as much as the images of a portrait. The term “technician,” often applied to Bailey, doesn’t necessarily require “cold” before it.

Following Bailey’s solo, the leader’s trumpet provides a cool contrast to Bailey’s heat, alto saxist Glyn Paque and pianist Sam Allen split a chorus and then a brief clam by one of the tenor saxophones provides another bit of timbral contrast. From there, Bailey continues to accompany and energize the band before all at once before reaffirming why the last chorus is often called a “shout chorus.”

He dominates four of this side’s six choruses, something hard to imagine earlier on in Henderson’s star-studded orchestra or later on in John Kirby’s tightly arranged sextet. Assorted pickup dates of the early thirties with Nelson, Noble Sissle, Bubber Miley, Mills Blue Rhythm Band and others are great opportunities to hear Bailey stretch out. Never expecting him to be an innovator or even an artist, Bailey’s various bosses knew he had plenty to offer. No “sideman” ever did the term prouder.

Don Murray, Baritenor Sax *REVISED*

So much for discographies! Here is a revision of an earlier post that accounts for some additional information.

-Your humble (occasionally to the point of error) blogger

Don Murray’s solo on “Blue River” with Jean Goldkette’s band came as a complete surprise. It wasn’t just being used to hearing him on baritone sax with Goldkette and on tenor with Ted Lewis, along with his clarinet in both settings. That would have just made my hearing a tenor sax spot for Murray with Goldkette a novelty.

Don Murray’s solo on “Blue River” with Jean Goldkette’s band came as a complete surprise. It wasn’t just being used to hearing him on baritone sax with Goldkette and on tenor with Ted Lewis, along with his clarinet in both settings. That would have just made my hearing a tenor sax spot for Murray with Goldkette a novelty.

The sound of this Murray tenor, so rich, so plummy, so far removed from the piping, reedy solos in the instrument’s upper-medium to high registers with Lewis was the real surprise. The first (through about fifth or sixth) time I heard it, it left me scratching my head. Yet it is in fact a tenor saxophone.

Small wonder since Murray was not even playing tenor sax. Blame my car speakers or blame Murray’s light, transparent as cheesecloth tone on baritone (and thank Albert Haim for educating me):

So many baritone players of this stylistic era played the big horn with a big, burly tone, thick vibrato and percussive articulation. Compare Bobby Davis, Harry Carney, Jimmy Dorsey, crunching Stump Evans, massive Cecil Scott (on “Harlem Shuffle“), Joe Walker, or bass-sax like Jack Washington with Murray, and the difference becomes clear to the point of world-altering.

Links with Murray’s frequent collaborator Frank Trumbauer are tempting. Yet the C melody saxist’s light timbre dovetails with a light, relaxed approach to improvisation. “Tram” often seems to ease into his lines, even at breakneck tempos. Murray’s approach was rarely easygoing. Even on “Blue River,” his wafer dark tone spirals into a rapid-fire kineticism. If Frank Trumabuer looks ahead to the cooler sounds of Lester Young And Miles Davis, Murray is firmly, and in hindsight refreshingly, part of The Jazz Age’s nervous energy.

Murray doesn’t cut “Blue River” to ribbons, yet well past paraphrasing it, he turns Joseph Meyer & Alfred Bryan’s repeated note theme into a busy, bouncing ballet of arpeggios, intervals, runs and an ecstatic in-tempo break after the ensemble bridge. His solo is halfway between complete abstraction and the type of recomposition Bix Beiderbecke (here buried in the section) was known for.

Decades of hearing Trumbauer’s own recording of “Blue River,” with Murray in the background and Bix Beiderbecke forever in the foreground, have made it all too familiar to generations of jazz listeners. Murray’s variation resembles cutting lines from Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead into acts of Hamlet. Goldkette’s arrangement may or may not be as hip as Trumbauer’s but for twenty-four bars Murray makes the tune an event. As for my own naive guesses initial impressions of Murray’s choice of instrument, I now know better but see the value in trusting one’s “gut” even as I continue to learn more about this often overlooked player. That’s a jazz musician for you.