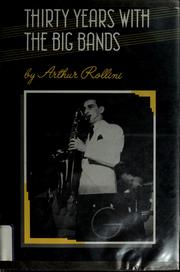

Peer through any “Top Ten Tenors” list and you just won’t find Arthur Rollini. When he’s remembered at all, it’s for his time with Benny Goodman’s epoch-making mid-thirties swing band. Yet as the title of Rollini’s autobiography indicates, he was a skilled enough saxophonist (and apparently devoted yet ultimately disappointed flutist) to make a career of Thirty Years With The Big Bands. Besides Goodman, Rollini played with sweet bandleader (and apparently very crass person) Richard Himber, the exacting, progressive-minded Raymond Scott and on a slew of pickup dates with a variety of jazz legends. Rollini must have done something right.

Peer through any “Top Ten Tenors” list and you just won’t find Arthur Rollini. When he’s remembered at all, it’s for his time with Benny Goodman’s epoch-making mid-thirties swing band. Yet as the title of Rollini’s autobiography indicates, he was a skilled enough saxophonist (and apparently devoted yet ultimately disappointed flutist) to make a career of Thirty Years With The Big Bands. Besides Goodman, Rollini played with sweet bandleader (and apparently very crass person) Richard Himber, the exacting, progressive-minded Raymond Scott and on a slew of pickup dates with a variety of jazz legends. Rollini must have done something right.

Rollini also had big ears to match that big talent. Alongside stories about life on the road, romantic boondoggles and references to “thoughtless…fickle…inconsiderate, etc. Benny [Goodman]!” his memoir is a who’s-who of pre-war talent. Far from name-dropping or even scattered recollection, Rollini effectually offers a listening guide to some now-forgotten musicians, artists who may not have all been innovators but were on bandstands and in recording studios making the music.

Here is Rollini’s extensive list of favorites, excerpted from his book in their order of appearance (emphases mine):

…Irving (Babe) Russin, who played fine tenor sax…Mario Lorenzi, also a good jazz harpist…Fred Elizalde, who was only twenty-three years old himself, a Cambridge graduate who played fantastic piano and arranged brilliantly…Bobby Davis, first alto sax…had a beautiful tonal quality on alto and baritone sax…Matty Malneck, a fine violin player (both concert and jazz)…

…Irving (Babe) Russin, who played fine tenor sax…Mario Lorenzi, also a good jazz harpist…Fred Elizalde, who was only twenty-three years old himself, a Cambridge graduate who played fantastic piano and arranged brilliantly…Bobby Davis, first alto sax…had a beautiful tonal quality on alto and baritone sax…Matty Malneck, a fine violin player (both concert and jazz)…

…Hymie Schertzer was now playing first alto sax [in Benny Goodman’s band]. Bill DePew was on the other alto sax, and Dick Clark and I were on tenors. It was a good sax section!…To this day Ziggy Elman had the most powerful sound that I have ever heard…Harry James was a genius. He could read all of the highly syncopated charts at sight, and he played fantastic jazz solos, different every time…also a good conductor and a fine arranger…Babe Russin, a great tenor man…no match for Vido [Musso]’s strong tone but made up for it with his keen ear and great drive…a good reader and read off all the charts at sight…Murray McEachern…a great talent…I must state emphatically, though, that the 1937-38 [Goodman] band was the best! Apart from Hymie Shertzer, who could swing a great lead alto sax, this band consisted entirely of jazz soloists of great talent…

…Hank D’Amico…was one man who did not try to imitate Goodman. He had a distinctive style of his own, and, as they now say, ears. He could read and transpose almost anything…Joe [Viola] was a schooled clarinet player and an excellent sax man…Ralph Muzillo…with an extremely strong sound and drive, was on first trumpet…Sid Stoneburn, a good clarinet player…Al Gallodoro, in my estimation the best technician of our day…could read and transpose almost anything; he was a self-taught musician and would often practice six or eight hours a day. He could double tongue, triple tongue on alto with ease and was magnificent…Abe [Osser] had absolute pitch…such a keen ear that he could detect a wrong passing note by one of the obscure violinists and could out the right one…Phil Napoleon, the fine Dixieland trumpeter…Johnny Bruno, a fine jazz accordion player…

…To this day, I think that Benny Goodman was still the greatest all-around clarinet player…a creator and influenced many players of his instrument throughout the world. I’ll have to give the number two spot to Artie Shaw, who was so great. The rest are up for grabs: Johnny Mince, Tony Scott, Peanuts Hucko, Barney Bigard, Pete Fountain, Abe Most, Buddy DeFranco, Gus Bivona, Hank D’Amico, Phil Bodner, Walter Levinsky, Mahlon Clark, Matty Matlock, Joe Dixon, Woody Herman, Clarence Hutchenrider, Sol Yaged, Bob Wilber, Buster Bailey, Marshall Royal, Joe Viola, Artie Baker, Paul Ricci, Tony Parenti, Jimmy Lytell, Sal Pace, Pete Pumiglio, Sal Franzella, Drew Page, Izzy Friedman and newcomer Dick Johnson…

Don’t forget Arthur Rollini! I’m willing to assume he knew his stuff and look forward to (re)hearing all of these musicians.