Alfie Evans appears in personnel listings with popular dance bands and next to several jazz legends. He didn’t change the course of music, but a little research shows he enjoyed a long musical career while earning kudos from colleagues and collecting some fascinating anecdotes. I hope you enjoy reading about him as much as I enjoyed learning about him.

Musical Roots

Alfred Lewis Evans was born on June 20, 1904, in the Pennsylvania borough of Olyphant. That middle name came from his Welsh-born father, who named his son after a late brother who had died in the Scranton mines.

Music was likely an important part of young Alfred’s life from the start. His father was the pianist for Olyphant Baptist Church and Scranton’s Strand Theatre. After moving to White Plains, New York, later in his life, the elder Evans continued playing with radio orchestras until his death at the age of 80.

Evans’s father also played trumpet while leading his own bands. As a Bucknell University student, arranger Bill Challis recalls Alfred playing “hot violin” with his father’s group as early as 1922. He was already going by “Alfie.” At some point, Evans met fellow Pennsylvanian and future swing star Jimmy Dorsey. He likely also met Jimmy’s trombonist younger brother, Tommy.

A childhood friend of the Dorseys remembered Alfie as a “violinist who switched to sax and clarinet after just three weeks of training with [Jimmy].” That was more than enough training. By the start of 1923, Evans was playing saxophone with the Saxons Society Orchestra. This elitely-named band also played hot dance numbers like “Chicago,” “Lovin’ Sam,” and “Toot Toot Tootsie.” By the start of the following year, Evans seems to have relocated to New York City. He may have moved there with his family; his marriage certificate indicates his parents were living in the city by 1926.

A photo from this period shows Evans with the Scranton Sirens when Billy Lustig led the group as “Billy Lustig and His Sirens Orchestra.” In an informative piece about guitarist Eddie Lang, researcher and audio engineer Nick Dellow notes that this “local band through which many dance band and jazz luminaries passed” played the Beaux Arts Café Atlantic City, New Jersey, for two weeks starting on New Year’s Day of 1924. Banjoist Jack Bland recalled Evans, both Dorsey brothers, Lang, and Morgan with the Sirens at that venue. Alfie was barely older than 20 and already keeping impressive musical company!

After the Beaux Arts gig, the Sirens embarked on a series of one-nighters, but it’s unclear whether Evans went on the road with them or stayed in the area. He joined Dinty Moore’s orchestra at the Hunter Island Inn in Pelham, New York, around May 1924. Variety reported this band playing “regulation jass [sic] stuff and selections from comic operas…[and] a cycle of Victor Herbert works.” Moore featured all his band members—“especially” Evans—as soloists. The magazine also mentioned Evans having played under Herbert, an esteemed conductor and composer.

Dance Bands

In a letter to historian Stephen Hester, tuba player Joe Tarto said Evans played clarinet and alto sax with Sam Lanin at the Roseland Ballroom in 1924. Biographies of Bix Beiderbecke also mention that Evans and cornetist Red Nichols were living in a hotel while playing with Lanin. Beiderbecke soon moved in when the Wolverines band came to New York.

Evans shared some unique views about his roommates in a letter to Beiderbecke biographer Phil Evans (no relation):

Red had all of the Bix recordings that were available, and he would play them over and over and again over. So, I knew Bix’s work very well before I met him…Red played most of Bix’s choruses on RCA Victor with George Olsen’s band…I found that Bix had ideas that were six years ahead of his ability to play them. He had a range of maybe a tenth, not much tone, but he could do wonderful things with his limited technique…[Bix] and I would sit up until the wee hours trying to wear out my new recording of Petrushka. Bix would sit there and drool over some of Stravinsky’s chords.

“Not much tone” will likely surprise many Beiderbecke fans (and the writer doesn’t know George Olsen’s records well enough to say who’s playing what on them). Evans sure had definite tastes and expectations in music!

But when did he join Lanin in 1924? A Billboard article from May 10, 1924, lists Lanin’s reed section as Larry Abbott, Maurice Dickson, and Merle Johnston. By October, Variety was reporting that “Lanin’s sax section—Clarence Heidke, Al Evans, and George Slater—are a crack trio for harmonies and rhythms.” That’s the same section listed in Tarto’s letter.

Johnson and Shirley’s American Dance Bands on Record and Film (ABDRF) lists Evans on a December 26, 1924, session with a Lanin group recording as Bailey’s Lucky Seven. That seems to be Evans’s first recording date, inaugurating a lengthy recording career. Tom Lord’s online Jazz Discography lists “Alfie Evans” and “Alfred Evans” on nearly 200 sessions. ABDRF shows 40 index entries, with many spanning multiple pages. That doesn’t count recordings outside the sometimes arbitrary labels of “jazz” and “dance music.”

Ironically, despite Evans’s extensive discography, it’s difficult to identify him as a soloist or in ensembles for most of his career (at least for this writer’s ears). Part of the issue is pinning down Evans’s “voice” on any of the instruments that multiple discographies assign him through all those personnel listings. Following that period’s sax section conventions, Evans often appears alongside at least two other reed players. Those players often doubled various permutations of reeds: clarinet and sometimes bass clarinet; soprano, alto, and/or baritone saxophones; and a decent amount of flute, oboe, and other orchestral reeds.

Doubling may be expected of professional musicians. Just being able to meet that expectation is impressive. Evans seems to have exceeded that professional standard for decades. His skill and versatility allowed him to not just survive but thrive for his entire career.

That still doesn’t help locate him on records. Discographies show Evans as the sole reed on two sessions with The Red Heads waxed for Pathe Actuelle on February 4 and April 7, 1926. Discographies are not perfect. Their sources aren’t always clear. Evans might not be on these sessions, but they might be the best opportunities to isolate his sound.

In the ensemble on “Poor Papa,” the clarinetist plays in syncopated accents between the cornet’s lead and the trombone’s counterpoint. It’s a different approach than the tumbling arpeggios and heavily inflected lines of some other players. In solos, the clarinet has a medium-bright tone with a slight sandiness in the mild register.

On alto for “‘Taint Cold” and “Hi-Diddle-Diddle,” the player crafts lines in stepwise phrases and short intervals. He displays a neutral tone and light vibrato that (to the writer) sound different from the lead/solo alto(s) on Lanin’s recordings at the time.

Evans continued to record with Lanin throughout the twenties. But his regular day job shifted. He moved between multiple groups filled with top musicians who had the skill and versatility to play hot dance music, complex arrangements, and the range of material required to be a successful working band—yet another indicator of Evans’s talent and hustle.

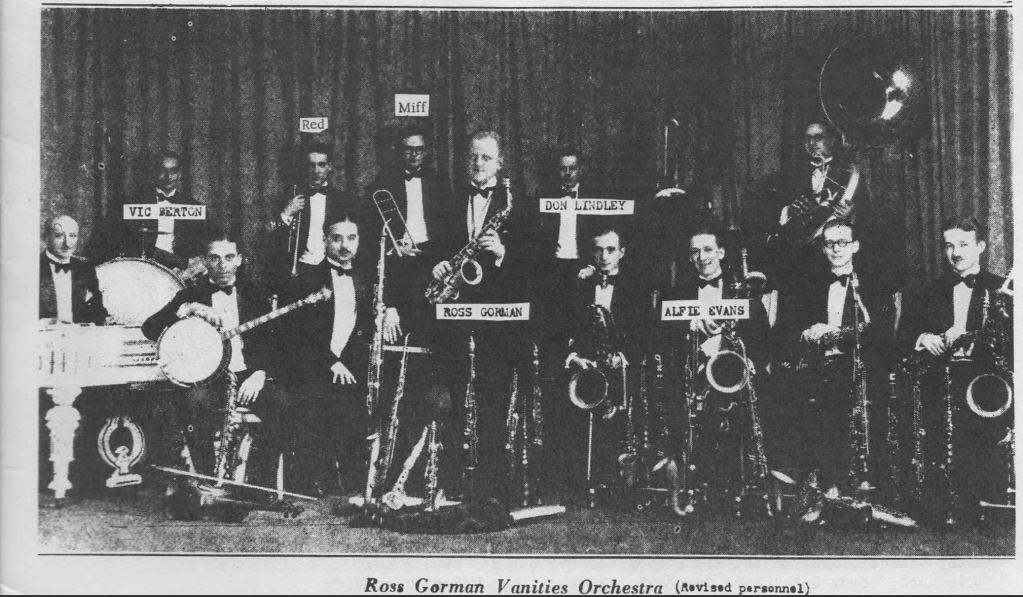

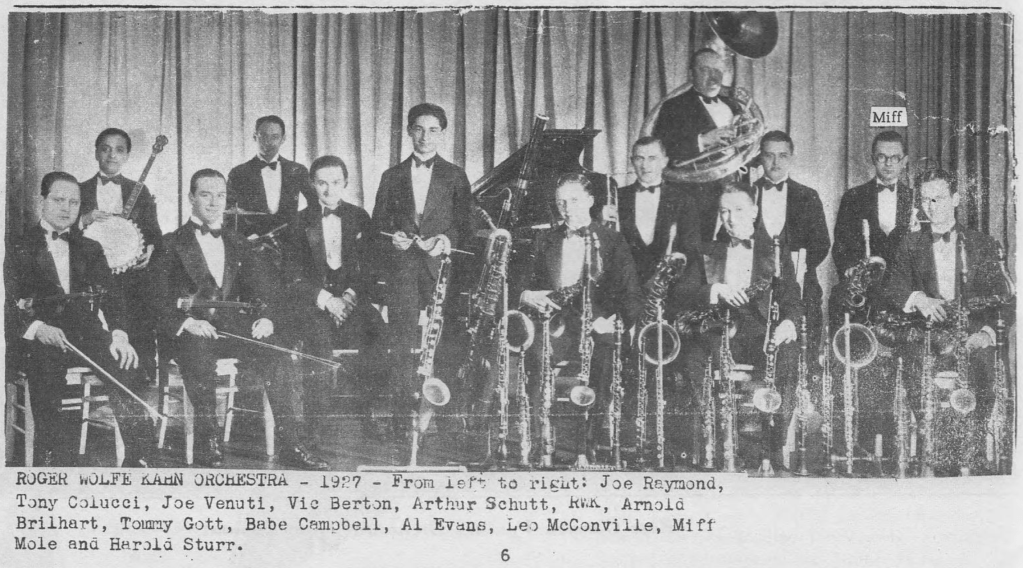

After joining Ray Miller’s band at the Arcadia Ballroom for the 1924 winter season, Evans may have spent time with Roger Wolfe Kahn in 1925 before officially joining him the following year. George Van Eps remembered Evans as part of the Kahn band—along with Vic Berton, Lang, and Joe Venuti—at Manhattan’s Pennsylvania Hotel during an instrument makers’ expo. By the summer of 1925, Evans was with Ross Gorman’s pit orchestra for Earl Carroll’s Vanities show as well as broadcasts on the radio and records made for Columbia. In addition to their multi-reed virtuoso leader, Gorman’s sidemen also included Tony Colucci, Miff Mole, and Nichols. Evans was still with Gorman through at least November.

Beside legitimate nightclubs and ballrooms, Evans also played the circuit of after-hours mob-run speakeasies. For many musicians of the time, working with organized crime figures was just part of the job. Evans seemed to enjoy a courteous, professional relationship with these gangster businessmen. He shared one story with his son and grandson highlighting this curious dynamic and Evans’s shrewdness in tough situations.

Over dinner with one venue’s management, Evans happened to admire a Cadillac driving by outside. Two days later, that Cadillac was parked on the lawn at his Long Island home. It wasn’t just the same model; it was (somehow) the exact same car. Evans thanked his employers but politely explained that he could not accept such a gift. He knew that accepting it would mean being indebted to the wrong people. Evans was extra cautious after hearing about a singer who ended up with maimed vocal cords after quitting a venue. He had to play for some dangerous people to make a living but diplomatically avoided any involvement outside professional music.

Evans recalled mostly playing alto sax at these jobs, which could last into the earliest hours of the morning. Unlike some of his fellow musicians, he skipped any alcohol-fueled carousing after the gigs. Evans’s son remembers his childhood home as a popular dinner spot for musicians and an occasional stopover when they were exhausted or hungover. One morning, as a little boy, he walked down the stairs to find Tommy Dorsey snoring on the family couch and sleeping off the night’s festivities!

By the start of 1926, Evans had replaced Dick Johnson in Roger Wolfe Kahn’s band at the leader’s Peroquet de Paris club on West 57th Street. The Kahn band was another group of all-stars that included Vic Berton, Arnold Brilhart, Tony Colucci, Tommy Gott, Lang, Leo McConville, Arthur Schutt, and Venuti.

He also accompanied his friend Rudy Wiedoeft in a saxophone ensemble concert at Aeolian Hall on April 17, 1926. Evans said that Wiedoeft saw working as a sideman as beneath him—which Evans thought was for the best because he considered Wiedoeft a poor section player!

A few weeks later, on June 7, 1926, Evans married his high school sweetheart, Myrtle Sullivan. They would have two children together: Alfred Jr., who went on to become a successful attorney, and Marjorie, a devoted worker in John F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign.

Evans continued recording with Kahn and recording with Lanin groups like the Broadway Bellhops and Ipana Troubadours through 1928. Red Nichols told Record Research writer John Steinert that Evans played alto in the ensemble on the cornetist’s dates for Edison as Red and Miff’s Stompers, but there are no solo, obbligato, or lead choruses to identify him. Evans may also be on records by Frank Farrell’s augmented recording band. After that, he recorded with the Dorsey Brothers, large orchestral bands led by Red Nichols on Brunswick, and some of Joe Venuti’s hot big band sessions as “The New Yorkers.”

Radio Career

Evans had plenty of work. Yet the birth of his first child in August of 1928 may have inspired him to seek more regular hours, company benefits, and other advantages of full-time employment while still doing what he loved.

At the time, the growth of radio networks opened up huge opportunities for musicians even as it hurt record sales and, to some extent, live performance. A radio gave listeners unlimited access to a variety of music without having to spend money on a 78 or a cover charge. Radio even managed to grow after the stock market crashed. Evans must have observed these trends and watched fellow musicians make the transition. With his ability, experience, and connections, it would have been easy for the new “Alfred Evans Sr.” to find work as a radio staff musician at a major network.

It’s unclear exactly when Evans started work as an NBC radio staff musician. He seems to have been in place by early October 1929 (if not sooner). If that was the case, his timing was impeccable. The stock market crash on October 24 signaled the end of the roaring twenties and the start of the Great Depression.

An article in the Jersey Journal dated October 11, 1929, paints a picture of Evans right at home in the NBC studio a few weeks before the financial collapse:

[Evans] works in a chromatic run that’s a ‘wow…’ Alfie Evans is the ‘sweet alto sax.’ But he too is wandering all over the studio tooting a clarinet into corners, through an old hat, anything to make it sound different. ‘Hey! Philly [i.e., Phil Napoleon] ’ yells Miff [Mole]. ‘Front and center! Let’s try this over with Alfie…’ Alfie warbles furiously on the clarinet, making it talk bass.

Evans could play sweet or hot as the occasion demanded. But jazz was just one element of the job description for a staff musician. Louis Reid reported on the day-to-day for these players:

The staff musicians of the broadcasters, craftsmen trained to play with a symphony orchestra one hour and with a jazz band the next, don’t get their names in the papers often nor are their names familiar to ear cuppers. Yet they occupy an important position in the radio scheme of things. Without them, the day’s run of programs would be a bleak affair. Approximately 1,000 musicians play every month in the studios of [NBC]. The staff musicians, however, are a smaller group. At present [around September of 1930], there are 75 men who report every day and who are the company’s musical backbone…These men must be versatile. They must be able to respond to the dynamic urge of Cesare Sodero when he is conducting opera, to the rhythmic baton of Hugo Mariani when the tangos of the Argentine are punctuating the ether, and to the feverish beats of William Daley when a jazz program is on the air…New conductors never worry them. Nor do new music scores. Whether Berlin or Beethoven stares at them from their music racks, it is all in a day’s work.

For Evans, the day’s work often put him front and center. Frank Kelly mentioned Evans as the “principal lead alto sax” on the NBC staff—a prominent role and crucial element in shaping an ensemble’s sound. He also played under the legendary conductor Arturo Toscanini in the NBC Symphony Orchestra (likely on clarinet, oboe, or other orchestral reeds); with esteemed violinist David Rubinoff for the popular Chase and Sanborn Hour; and with Murray Kellner on the Let’s Dance show in 1935.

The “Kel Murray” society orchestra and Xavier Cugat’s Latin group alternated with Benny Goodman’s increasingly popular swing band. Kellner likely provided the more sedate musical offerings on Let’s Dance. But he led an army of generals with the likes of Arnold Brilhart, Hymie Farberman, Manny Klein, Sammy Lewis, Charlie Margulis, Arthur Schutt, and concertmaster Louis Raderman. Evans was also a featured soloist playing saxophone compositions by Wiedoeft and Andy Sannella and a marquee accompanist for singers such as Chick Bullock, The Bonnie Laddies, and Smalley and Robertson.

Radio work could pay far more than union scale. Even during the leanest years of the Great Depression, Evans did quite well for himself. He provided for a growing family in his home on Long Island Sound. He picked up sailing after purchasing a boat. And he supported several relatives outside his immediate family amidst the country’s economic hardships.

Evans watched several musicians in his circle move from sideman to star soloist to bandleader. But he was happy in his role. Evans’s grandson recalls his grandfather mentioning a professional “fork in the road” he simply didn’t want to take. Maybe he saw some of his colleagues’ sacrifices to become “really big.” Perhaps the work/life balance was just right for him as is.

With a newborn in the house and during a depression, the regular paycheck and steady hours were probably blessings. And set hours suited Evans’s demeanor. Alfred Jr. remembers his father as a homebody and family man. He loved his job as a musician but also enjoyed coming home to spend time with his wife and their children.

In that regard, Evans resembled one of his musical idols: Frank Trumbauer, another saxophonist who preferred being home with his family to partying after the gig. Ruth Shaffner Sweeney, Bix Beiderbecke’s girlfriend, said Trumbauer “never cared much about going out after hours. When Bix, Pee Wee [Russell], and the other members of the [Jean Goldkette] band went out with my sisters and me, Frank would always go home. He had an adorable wife and little son, and he was a homebody type.” Swap out a few names, and this may be an accurate description of Evans.

In a letter to Beiderbecke biographer Phil Evans (no relation), Alfie Evans expressed earnest admiration for Trumbauer:

I fell in love with his work long before I ever met him. Sax men, in the early days, spent much time and effort trying to develop a tone that didn’t sound like a buzz saw going through a pine knot…along came ‘Tram,’ with his easy, flowing way of playing a tune full of interesting little turns, etc. without destroying the tune.

Even among the incredibly talented but often anonymous pool of studio musicians, Evans collected his own admirers. When listing radio musicians who exemplified the skills he described, Louis Reid put Evans at the top of his list. In a 1930 retrospective of Ross Gorman and his alumni, columnist Graham McNamee mentioned Evans as “one of the best radio saxophonists” at the time. In his Tune Time magazine column, violinist Jack Harris described Evans as “one of the most valuable men in the dance world today. He plays a hot fiddle almost as well as Venuti, and his clarinet and saxophone work is simply astounding.”

Orchestral saxophonist and teacher Larry Teal called Evans, Arnold Brilhart, and Merle Johnston “the top section in New York.” An ad for Conrad reeds lists Evans as one of the “prominent reed players” endorsing their products along with Arnold Brilhart, Chester Hazlett, and Artie Shaw. In 1940, among the likes of Louis Armstrong, Harry James, Ziggy Elman, Jack Teagarden, Miff Mole, and Mannie Klein, Evans also contributed his expertise to a volume on The Answer to Wind-Instrument Playing Problems published by M. Grupp Studios.

Evans also acquired some celebrity status among his son’s schoolmates. On a class field trip to Manhattan to watch the NBC orchestra, Evans greeted his son after the performance. A dumbfounded Junior watched his classmates gather around his father for an autograph!

Some of Junior’s school friends may have recognized his dad from the big screen. As a member of Henry Levine’s band on NBC’s Chamber Music Society of Lower Basin Street program, Evans was audible and visible in numerous “Soundies.” In addition to these short music videos played on jukebox screens and movie theaters during the forties, the group broadcast nationwide and made records for Victor.

Music critic Scott Yanow describes the show as “a satire of classical music broadcasts where the announcer could often be stuffy, excessively high-brow, and a little too intellectual for his own good…the show had all of the musicians being introduced as either Professor, Dr., or Maestro [and] mixed together humorous commentary and occasional comedy acts with excellent music.”

The Lower Basin Street band exudes an easygoing swing and bright dynamic with obvious warmth and humor. Nick Dellow interviewed its leader, Henry “Hot Lips” Levine, and summarizes the trumpeter’s legacy and ability:

Levine was a veteran jazz and dance band musician who had briefly played with the Original Dixieland Jazz Band in the early 1920s, subsequently becoming established as a reliable sideman who could turn out respectable hot solos when required. He was part of the close-knit coterie of studio dance band musicians in New York, often “subbing” for Red Nichols when Red was too busy to fulfill studio dates. Evans undoubtedly knew Levine in the 1920s.

Chamber Music Society broadcasts often featured a famous guest musician like Sidney Bechet, Benny Carter, or Jelly Roll Morton. Evans was just one of the crack musicians in the group playing with these greats. He also played reeds in Paul Laval’s jazz-oriented woodwind ensembles on NBC.

The four horns of Levine’s octet often combined for “orchestrated Dixieland,” trombonist and historian David Sager’s term for a voicing with “the first available harmony line [usually taken by the trombone] below the cornet lead, while the clarinet [takes] the first available harmony above the lead.” Rudolph Adler’s tenor sax added a fourth voice to the typical front line of trumpet, trombone, and clarinet, which added body to this exceptionally bright harmonic stack. Playing as a harmonized section also provided textural contrast to solos and collectively-improvised ensembles.

Picking out solos in this ensemble-based style is an anachronistic approach. But these are the best recordings to hear Evans. Highlights include him having a ball playing obbligato behind Linda Keene’s vocal on “When My Sugar Walks Down the Street” and his long lines in “Ja-Da.” “Georgia On My Mind” is just Evans and piano god Art Tatum over the rhythm section.

Retirement

It’s unclear exactly when Evans left radio work and, seemingly, full-time professional performance. He was still working in that capacity by 1950 but was running a music store by 1960. The NBC Symphony Orchestra stopped broadcasting after 1954, so perhaps that was his cue. After leaving NBC, he taught lessons at his White Plains store and a studio on 44th Street between Sixth and Seventh Avenues.

An advertisement in Woodwind magazine humbly states, “Alfie Evans, radio and recording artist now accepting students on saxophone and clarinet.” He didn’t need to say much more than that. Saxophonist Ray Beckenstein explained that, when he was seeking a teacher after joining Bobby Sherwood’s band, “The saxophone teachers in New York [around the early forties] were Merle Johnson, Alfie Evans, Henry Lindeman, and Joe Allard. Those were the people that everybody went to, to study saxophone.”

By 1970, Evans had retired and moved to Florida. His grandson remembers visiting him in an age-restricted community in Deerfield Beach, near Boca Raton. He never saw his grandfather pick up an instrument, but he recalls a keen interest in photography and plenty of high-end equipment. When a representative from the Polaroid company demonstrated their product to potential investors, Evans declined because he thought the photos were of inferior quality. He looked at the photos as a connoisseur (not a consumer) and was just as discerning of photography as music. Evans was also an amateur meteorologist. “Grandpa” kept huge maps with multicolored pins plotting hurricane trajectories. Golf was another favorite pastime.

Evans’s activities in his senior years, and their apparent distance from anything musical, point to someone who had truly retired from music. He might have viewed music as a job he loved, but a job nonetheless, and one he was ready to move on from. He may have wanted to use his time to explore other interests. Maybe he still played music on his own terms, without an audience, and purely as a form of expression and a craft all to himself. Following complications from a fall, he passed away in 1991 at the age of 87. His wife of over 65 years died soon after.

More Than Jazz

“Sidemen, section players, studio guys”: whatever else we call these incredible talents, discographies are full of musicians who doubled multiple instruments but rarely soloed on them. Their contributions are now often viewed through a jazz lens. Nowadays, that usually means a laser focus on soloists, improvisation, and contemporary ideas about what counts as “Jazz.”

Widening the lens, Evans becomes more than a guy in a section or a name in a discography. He remains someone who, by working hard at his musical craft, played a unique role in American music. Sustaining a lifelong career by expertly playing several instruments well enough to perform with the company Evans kept is remarkable. That would be the case if he never improvised a single note. May we all be fortunate enough to have such talent and passion (that can also pay our bills).

Appreciation

Many thanks to Alfie Evans’s grandson for graciously speaking to the writer and sharing information about his grandfather and his father. Thanks also to Nick Dellow for reading through this article and providing suggestions.

Sources

In addition to the articles and books below, ancestry.com provided several census, death, marriage, and military records as well as ship passenger lists and other documents. Many sources were retrieved online through archive.org, The Bixography Discussion Group, and newspapers.com.

- “200 at Clique Club Dance in North Jamaica” in The Daily Star of Long Island City, Queens, on December 13, 1932

- “A Thumbnail Sketch of Frank Farrell’s Career” by Woody Backensto in Record Research 65

- “As I Knew Eddie Lang” by Jack Bland in The Jazz Record

- “Band and Orchestra Reviews” in Variety on August 27, 1924, and October 8, 1924

- “Bill Challis” in Jazz Gentry by Warren Vache

- “Concert Bureau to Present All-Star Program Tonight” in Elmira Star-Gazette on December 7, 1928

- “Eddie Lang: The Formative Years, 1902–1925” by Nick Dellow in VJM 167

- “I Remember…” by Jack Harris in Tune Times of January 1934

- “Lewis Evans, Musician, Dies” in The Tribune of Scranton on July 19, 1960

- “On the Radio Last Night” in Brooklyn Daily Eagle of March 20, 1928

- “Psychology Not of Jazz But of Jazz Musicians” in Jersey Journal of Jersey City on October 11, 1929, via Ralph Wondrascheck on The Bixography Discussion Group

- “Ray Beckenstein” by David J. Gibson in Saxophone Journal, volume 12 (1987).

- “Saxophone Sense” by Frank G. Chase in International Musician of March 1942

- “Symphony and Swing Can Be Mixed” in Down Beat of December 1937

- “The Voice of the Anthracite is Heard in Splendid Concert” in The Times-Tribune of Scranton on January 27, 1923

- “Two of a Kind” in International Musician of September 1940

- “Variety Of Music And Church Services Are Weekend Air Features” in Rochester Times-Union on May 26, 1928

- “Washington’s Birthday to Be Commemorated on Radio Today” in Rochester Democrat and Chronicle of February 22, 1929

- “Where Are They Now” in Frank Kelly’s “Reminiscing in Tempo” column from Record Research 109, February 1971

- Ad for Conrad reeds in The International Musician of November 1938

- Ad in Variety on November 4, 1925

- American Dance Bands on Record and Film by Johnson and Shirley

- Announcement in Orchestra World of January 1926 cited by Albert Haim on Bixography forum

- Article about staff musicians in Louis Reid’s “The Loud Speaker” column in Syracuse Journal of September 13, 1930, cited by Albert Haim on The Bixography Discussion Group and available on Tom Tryniski’s Old Fulton NY Post Cards website

- Billboard on May 10, 1924, cited in ABDRF

- Bix: The Leon Bix Beiderbecke Story by Phil Evans cited by Albert Haim in The Bixography Discussion Group

- Buffalo Evening News of July 3, 1930

- Evans in “More About Fud” by Richard DuPage in Record Research 25

- George Van Eps quoted in Lost Chords by Richard Sudhalter

- Internet message with Nick Dellow

- Jazz and Ragtime Records, 6th, ed., by Brian Rust

- Jimmy Dorsey: A Study in Contrasts by Robert L. Stockdale

- Letter from Evans to Phil Evans from the Richardson-Sloane Special Collections Center of the Davenport Public Library

- Liner notes to The Complete Wolverines 1924–1928 (Archeophone (RCH OTR-03) by David Sager

- Alfred Evans Jr.’s obituary in The Atlanta Journal-Constitution on May 2, 2009

- Phone conversation with Alfred Evans III

- Profile of James Crossan as a teacher in an ad for the Lopez Music House in Allentown Morning Call on April 22, 1937,

- Profile of Ross Gorman in “Graham McNamee Speaking” column in The Sunday Star of Washington, DC, on November 2, 1930

- Radio listings in Hartford Courant of April 25, 1930

- Richard DuPage’s article “Miff Mole: First Trailblazer of Modern Jazz Trombone” in Record Research 34 of April 1961.

- Rochester Times-Union of May 7, 1928

- Rubinoff’s Chase-Sanborn Orchestra recording of “The Betty Boop Song” per Marc F. on Facebook.

- Saxophones in Early Jazz by Karl Koenig

- The American Dance Band Discography, 1917–1942 by Brian Rust

- The Jazz Discography online, ed. Tom Lord

- The World-News of March 8, 1929

- Interview with Larry Teal on July 30, 1983, cited by Harry R. Gee in Saxophone Soloists and Their Music: An Annotated Bibliography

- Tram: The Frank Trumbauer Story by Phil Evans

- Variety of July 22, 1925, as cited in Richard DuPage’s article “Miff Mole: First Trailblazer of Modern Jazz Trombone” in Record Research of April 1961