“There are only two kinds of music: good music, and the other kind.”

People usually credit Duke Ellington with this phrase, or some variation of it, without specifying where or when he said it. We also don’t typically include the exact section of Genesis for “Am I my brother’s keeper?” or Star Trek II for “the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few.” A citation can seem pedantic in its redundancy.

I’m a member of a small group: people who have been told they like “the other kind” of music and care why it’s not “good.” I often wonder what Ellington meant by this statement. So, I got pedantic and tried to find a citation.

Sources

The best connection to a literary source I could find was by Alex Ross, who cites Ellington’s article “Where is Jazz Going?” from the March 1962 issue of the Musical Journal.

In that piece, Ellington reflects on the “future of jazz.” He considers whether musicians with “a background of educational equipment that is way out ahead” of earlier jazz musicians will affect the music’s folk roots. Ellington highlights the need to grow a supportive audience. He describes being told his music isn’t sufficiently Black and why rock and roll is the most “raucous form of jazz.”

The piece is worth reading in full, but I was looking for this passage:

“As you may know, I have always been against any attempt to categorize or pigeonhole music, so I won’t attempt to say whether the music of the future will be jazz or not jazz, whether it will merge or not merge with classical music.

There are simply two kinds of music, good music and the other kind. Classical writers may venture into classical territory, but the only yardstick by which the result should be judged is simply that of how it sounds. If it sounds good, it’s successful; if it doesn’t, it has failed. As long as the writing and playing are honest, whether it’s done according to Hoyle or not, if a musician has an idea, let him write it down.

And let’s not worry about whether the result is jazz or this or that type of performance. Let’s just say that what we’re all trying to create, in one way or another, is music.”

Ellington was not simply stating that jazz and classical music were equally worthwhile; listening to both can demonstrate that. He sounds interested in expanding appreciation for a broader range of music. He ends this passage and his piece with a summary rejection of labels.

At the same time, Ellington witnessed the classical/jazz binary at work since the start of his career. He flanks his soon-to-be-famous words with comments on classical music, highlighting his skepticism of musical hierarchies. As one commenter points out, Ellington was aware of shifts in popular music and diminishing opportunities for musicians in his specific branch of “good music,” so there might also have been a subtle but pointed commentary on “the other kind” of music selling out venues.

Ross goes on to mention an earlier source for this idea, one well outside of jazz, American popular music, or the twentieth century. In the following passage from his 1863 book Social Life in Munich, English jurist and writer Edward Wilberforce attributes the quote to Italian opera composer Rossini (1792–1868):

“Rossini’s saying about music applies to painting. Rossini is supposed to have said to some learned gentleman who was entertaining him with a discourse on nationalities in music, ‘My dear sir, there is no such distinction as you suppose between Italian, French, and German music; there are only two kinds of music, good and bad.’”

Rossini was interested in geographic boundaries applied to music. Critics dismissed his works as frothy, florid stuff best suited for Italian audiences. Some described Rossini’s music as too “German” in its scoring. While Ellington is disputing hierarchies, Rossini is sweeping aside borders.

Both composers encountered criticism about the cultural authenticity of their music and its accessibility. Despite being separated by an ocean and a century, and though they arrived along slightly different paths, both reached similar conclusions. They also avoid describing “the other kind” of music. Ellington won’t even use the word “bad.” Maybe he was having fun with implications. Perhaps he didn’t like such a drastic label. Either way, Rossini had no such issue.

As for who said it first or where they might have heard it, Ross says that “the real source” of this quote is probably Franz Grillparzer, an influential Austrian playwright. The relevant text appears in the 1856 poem “An die Kritiker.” Here is Ross’s translation from German:

To the Critics

The critics, meaning the new ones,

I compare to parrots,

Who have three or four words

That they repeat in every place.

Romantic, classical, and modern

Seems a judgment to these gentlemen,

And with proud courage they overlook

The real genres: bad and good.

It’s unclear if Grillparzer is discussing drama, music, or the arts in general. “Romantic, classical, and modern” can mean both eras and styles. But the quote still resonates. Here, it’s just one part of a larger assault on critics—not just on an idea, but people! Grillparzer is more upset by their overuse of musical labels than by the existence of those labels. “Good and bad music” is the knockout punch in a bigger fight.

Uses

At this point, the chain of authorial custody became less interesting than the usage. A quick search of different online resources revealed hundreds of quotations, misattributions, and possible plagiarisms—though, again, we rarely hear a source for “do unto others, etc.”

For example, this writer for the Bath Weekly Chronicle and Herald of July 20, 1865, could be accused of plagiarizing Rossini, referring to common wisdom, or even relying on what might have already become a cliché:

“[Conductor] Luigi Arditi is unlike most maestri, for he has neither prejudice nor partiality: He only recognizes two kinds of music: good and bad. German, French, Italian, or English, is alike to him, so that it be only first rate.”

The Bath Chronicle of March 8, 1888, was over-generous in its attribution, suggesting collaborative authorship:

“Rossini once told [French opera composer] Gounod that he only knew two kinds of music, good and bad, and Gounod himself says, ‘I dislike all this nonsense about German music, Italian music, French music, and so on: geographical boundaries cannot hedge in harmony.’”

Nearly 60 years later, Metronome writer Arthur McAuliffe (in his “A Treatise on Moldy Figs” from August 1945) retrofits the wisdom by substituting jazz styles for European schools:

“The truth surely is that Metronome judges everything on its individual merits and has only two kinds of music in mind—good and bad—instead of making arbitrary divisions into New Orleans, Chicago, etc. or jazz and swing.”

Jazz lovers may have been splitting those hairs. For classical snobs, “good music” and “bad music” were practically synonyms for “the music of an elite group of primarily Western European composers performed in concert settings and not marketed for mass consumption” and “the other kind,” respectively.

Ellington took on the longstanding “debate” in his piece. In “Meredith Wilson Takes This Stand” (Band Leaders and Record Review, April 1947), the writer uses the quote for more direct criticism of the classical community for looking down on jazz. Composer and bandleader Victor Herbert was fighting these hierarchies decades earlier from other spaces in American popular music. He includes the quote in a few articles, but this interview from the Cincinnati Enquirer on January 6, 1918, is representative of his views:

“When you really analyze music, there are only two kinds: good music and bad music. The mere fact that a certain composition is the work of one of the classicists, or that it is written in the classic style, does not necessarily make it a fine, good work. Nor does it follow that all light opera music is trashy. On the contrary, it is just as artistically important to have good light music as it is to have good music in the larger format.”

As late as 2000, Ray Charles (per Bill Milkowski, “Midnight and Steve Turre,” JazzTimes, October 2000) used the quote to argue that classical music doesn’t get to be grandfathered in as “good music”:

“Duke Ellington once said that there are only two kinds of music: good and bad. And it’s the truth! Because you can find beautiful, good music in every branch of music. And don’t let nobody fool you when they say, ‘All classical music is good.’ That’s a lie, ’cause it ain’t. Just ’cause it’s classical, that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s good.”

Ellington’s quote can become an invitation to seek out new sounds or a subtle dig at listeners who prefer chaff to wheat. Gene Lees, in his Jazzletter of January 1982, mentions “a remark attributed variously to Duke Ellington, Claude Debussy, and Richard Strauss that holds that ‘there are only two kinds of music: good and bad.’” He then expands on the quote:

“But try to ‘prove’ that a certain piece is good or (which is harder) that another is bad. Good or bad intonation, good or bad harmonic motion and voice leading, economy of means and its opposite, all the things by which refined judgment of music is made, mean nothing to someone whose experience has not prepared him or her to notice them. Lalo Schifrin has referred to most contemporary pop composers as ‘diatonic cripples,’ and Clare Fischer, on the same subject, describes ours as an age of ‘harmonic regression.’ They are both right. They are both irrelevant to someone jiving down the street with a Walkman mainlining moronic music into his brain.

For a similar repurposing in an academic setting, there’s William M. Lamers’s article, “The Two Kinds of Music” (Music Educators Journal, 1960). Lamers was the assistant superintendent for the Milwaukee public school system. Note the “Newton’s apple” origin for the quote:

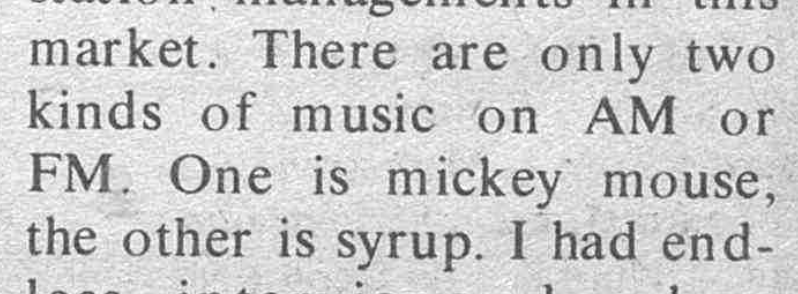

“Long ago, I was struck with the fact that there seem to be two kinds of music: ‘Great’ music, ‘good’ music—to say ‘the classics’ would not be quite accurate—the music we teach in our schools. (2) ‘popular’ music, which we eschew in our school programs as something inferior. Apart from the schools, 16 years ago, in most places, most of the time, ‘popular’ music of a rather low order was the music most Americans lived by. It crowded better music off radio and television. It blared in barber shops and stores. It was what people sang, what the young people in our schools delighted in when they escaped from the control of the school. We seemed then to suffer from a nemesis of less than mediocrity. And for the life of me, I don’t find much change from that pattern today.”

Lamers’s subsequent guidance for his colleagues shows he was a staunch advocate for music education and musical refinement outside the classroom. Alongside his advice to fellow teachers, his suggestions for the larger community include complaining about the music being played inside local businesses and organizing students “in a crusade against musical trash.” To Lamers, musical trash is easy to hear—though he also warns fellow educators to “watch your own [musical] tastes.”

These arguments enlist the quote to reinforce musical hierarchies. It would be excessive to paste it here, but Allan Bloom devoted an entire chapter of his 1987 book The Closing of the American Mind to that end.

On the other hand, for Alonzo Levister (“What is This Thing Called Jazz,” Jazz World, March 1957), the quote is a call to pride in one’s subjective tastes:

“There are, fundamentally, only two kinds of music—good and bad. If it moves you, it’s good. If not, it’s bad.”

Louis Armstrong never seemed embarrassed by what anyone thought was “good.” He had big ears and a drive to bring his music to new and wider audiences. Armstrong scholar Ricky Riccardi explains that Armstrong actually credited the quote to trombonist Jack Teagarden, but because Armstrong almost always quoted Teagarden, people attributed it to Armstrong! He would also occasionally use it without mentioning Teagarden. I haven’t found the interview, but Phillip D. Atteberry (in “A Century of Satchmo,” The Mississippi Rag, April 2001) mentions one such exchange with Edward R. Murrow.

Trummy Young and Kid Ory were both trombonists who played with Armstrong. Young recalled Ory “once telling a San Francisco reporter that ‘there is [sic] only two kinds of music: good and bad.'” Young took the quote as a source of didactic inspiration. To him, it meant that “aspiring musicians should ‘listen to all good music and try to work out their own style. Learn as much as possible and practice for good technique'” (from Charles E. Martin, “Trummy Young: An Unfinished Story,” The Second Line, Summer 1978).

Here are a few more attributions from the jazz pantheon:

“Current Biography reported as far back as 1944 that Eddie Condon scoffed at the concept of ‘Chicago-style’ musicians, saying, ‘There are only two kinds of music: good and bad.’ (I’ve also heard that line attributed to other musicians at one time or another, but Condon is on record as having said it a half century ago.)

—Chip Deffaa, “Discusses Eddie Condon: Town Hall Volume 9,” Jazzbeat, Fall 1993”

“I never liked the idea of categorizing music, though. I think Kenny Clarke was right when he said that there are only two kinds of music: good or bad. But I think the industry and consumers need guidance, or help, with jazz music.”

—Peter Schmidlin quoted in David Zych, “Label Watch: TCB,” JazzTimes, December 1997

“For instance, the great ragtime player-composer Eubie Blake, a close friend of [Max Morath]. ‘Eubie said there are only two kinds of music,’ says Max. ‘Good…and bad.’”

—review of The Road to Ragtime in Jazzbeat, Winter–Spring 2000

When Woody Herman passed away in 1987, several articles included the quote, starting a game of “jazz wisdom telephone.” Two days after Herman’s death, an obituary in The Miami Herald on October 31, 1987, quoted him citing Duke Ellington and Igor Stravinsky. An obituary for Herman in the Star Ledger of Newark, New Jersey, on November 2, 1987, included the following:

“For Woody Herman, at all times in a durable and incandescent career, there were only two kinds of music: ‘good and bad.’”

A letter to the editor in the Los Angeles Times published on November 15, 1987, said that the writer “recently heard” the quote from Woody Herman. Numerous articles used some version of the quote in pieces on Herman.

Naturally, the quote spoke to a wide range of artists. Here’s Noel Redding (in an interview with him and the rest of Jimi Hendrix’s band published in Jazz & Pop, July 1968) adapting it to Woodstock parlance:

“There are only two kinds of music—good and bad—regardless of what you play or what sort of bag you might be in.”

A profile of country artist Reba McEntire published in multiple publications during 1987 quotes her as saying, “Don’t categorize me or my music. There’s only two kinds of music to me: good and bad.” Between Herman’s passing and McEntire’s scolding, 1987 was a banner year for the quote; mentions of it spiked across the United States.

Kiss co-founder Paul Stanley also used it in an interview published in several newspapers during March 2021. Blues musician and scholar Kat Danser (in a profile by journalist Paul Tessier for The Morning Star of Vernon, British Columbia, on March 15, 2019) said that “when you go down south, everybody says, ‘There’s only two kinds of music: good music and bad music. Danser varies the meaning here slightly, chalking the phrase up to a regional insight.

Substitutions

At different points, speakers swapped in other categories for “good music,” “the other kind,” and “bad music.” Not all of them were intentional, and they probably illustrate the speaker’s individual priorities more than their musical philosophy. For example, in a letter to the Cornish Guardian of February 21, 1908, one correspondent declared, “There are only two kinds of music: sacred and silly,” explaining that “everything good in the world is sacred,” taking rarefied taste into spiritual territory.

The erudite, caustic journalist H.L. Mencken was likely familiar with the quote through some classical attribution. In a letter dated March 6, 1925, he wrote that “There are only two types of music: German music and bad music.” Mencken was not being ironic. He genuinely believed in the superiority of his native culture. Sometimes musical taste is about much more than music.

Let’s end with maybe the broadest, most down-to-earth, and humblest variation, by a young artist finding his way. Ornette Coleman was likely familiar with the quote, probably through Ellington, so it’s easy to imagine this as a riff on Ellington’s wisdom:

“I think when I was coming up (starting) to participate in instrumental music, I hadn’t really thought about the problem of what instrument, what kind of music or what. I just thought that since there were only two kinds of music, vocal and instrumental music, there would be enough space left for me to participate in instrumental music.”

—Ornette Coleman, “What Do You Play After You Play the Melody? John Litweiler Talks to Ornette Coleman,” Disc’ribe, Fall 1982.

His modesty is incredible: Imagine Ornette Coleman wondering if there’s room for him!

There’s much more to “good and bad music,” but at this point, who said it is first far less interesting than why so many people keep saying it. I still don’t know which bucket my musical tastes fall into. Most of the speakers don’t spend a lot of time explaining “the other kind” of music, which reminds me of another piece of often unsourced wisdom:

“If you don’t have anything nice to say, don’t say anything at all.”

Thanks

Many thanks to Ricky Riccardi and Michael Steinman for finding material and sharing their thoughts on this topic. Also, thanks to anyone reading this and some of the more abstract posts I’ve been sharing recently.