This blog is thrilled to welcome a guest post from Colin Hancock: a bandleader, multi-instrumentalist, researcher, and sound preservationist who has built his musical career around playing, recording, and documenting early jazz, blues, ragtime, and old-time music.

Colin Hancock has worked as a producer, curator, and researcher on several historical albums, including Grammy-nominated compilations.In 2023, Hancock and Mark Berresford wrote the liner notes for The Moaniest Moan of Them All: The Jazz Saxophone of Loren McMurray (Archeophone, 2023), which received a Grammy nomination for Best Historical Album that year. Hancock’s liner notes for The Missing Link: How Gus Haenschen Got Us from Joplin to Jazz and Shaped the Music Business (Archeophone, 2020) received a Grammy nomination in 2020. In addition to his ongoing research projects, he writes the “Discographical Ramblings” column of Vintage Jazz Mart magazine, the world’s oldest magazine for collectors of vintage jazz and blues records.

Colin Hancock regularly plays with and leads bands nationwide at various venues and events. While studying at Cornell University, he founded the Original Cornell Syncopators—a 12-piece dance orchestra that toured the United States, headlined the San Diego Jazz Festival, and recorded an album for Rivermont—Colin also operates the Semper Phonograph Company, one of the few operations in the world specializing in acoustical cylinder and disc recording.

Please enjoy this typically insightful and vivid piece of scholarship and the accompanying playlist from Colin!

The first time I heard the trumpet playing of Frankie Quartell (1901–1984), I was confused. While perusing the titles of a reissue of Okeh dance band oddities, I heard the 1924 rendition of Elmer Schoebel’s “Prince of Wails” by Quartell’s band, and it wasn’t much like any other rendition of the tune I was familiar with. His sound was not conventional: shaky, almost quavering at times, yet powerful and directional—he knew how to lead a band and shape every phrase. It seemed old-fashioned in some ways, harkening back to Ray Lopez and Louis Panico’s vibrato and subdivision of notes. But it also seemed abstract: those guys often played hot solos and offered the occasional or orchestrated lead. Quartell led in an almost folksy manner, sort of like a pastor or cantor leading a congregation. My confusion eventually turned to intrigue.

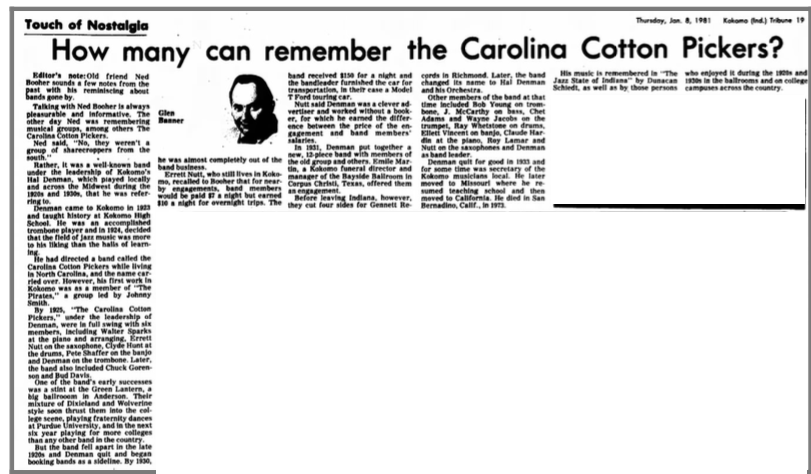

Over time, I have accumulated much information on Quartell with the help of many great jazz scholars and friends. Jazz legend Vince Giordano pointed me in the direction of an interview from the University of Texas at El Paso conducted in 1977, which set up a framework to start digging. I compiled a list of bands he played with—Ben Pollack, Isham Jones, Paul Biese, Art Kahn, Nick Lucas, Arnold Johnson, Dan Russo and Ted Fiorito—practically a laundry list of Chicago’s most popular dance band leaders. I heard tales from Kevin Coffey of Quartell’s own tours in Texas, Louisiana, and even Mexico, only adding to my intrigue. A closer look at some of the non-Chicago acts he worked with (like Paul Whiteman, Marion Harris, Paul Specht, and even a Wisconsin territory band) demonstrated that he was not afraid to put down roots in multiple groups. This is a side of musicians far too overlooked by scholars who often vilify musicians’ need to afford a bite to eat. Quartell is a perfect example of how this is woefully unjust and was as much a part of a working musician’s life then as it is now.

So, why does it all matter, and why is Quartell virtually unknown today? I think a lot of people don’t know about Quartell because he is hard to pinpoint. After all, describing him as a “jobbing, ragged, second-generation, Chicago-meets-territory trumpeter-bandleader” is an understatement! He doesn’t just exist as a dichotomy but as a representative of so many things happening in jazz, Chicago, and the world in those days. I think this is where his real value is: his career is like rings on a tree, with each event demonstrative of a milestone in the music and the world of the first half of the twentieth century while still indicative of the unique environment that created him. From confusion to intrigue, my approach to Quartell had finally developed into appreciation. I hope your opinion will follow a similar trajectory.

The Outer Ring: The Quaratiellos

Frankie Quartell’s early years begin like so many Chicago jazz musicians, with a story of immigrants overcoming the near-inconceivable obstacles of moving across the world in that era. His parents, Vincenzo (1864–1944) and Crestina (1868–1941) Quaratiello, were both Italian, moving from the southern Italian hill town of Ruvo del Monte in the province of Potenza to Chicago in the 1880s. The Quaratiello family settled in the city’s 19th Ward on the “Near West Side,” described at the time as the “most desolate part of the city,” notorious as the neighborhood where the treacherous 1871 Chicago fire began. It was a rough part of town, and Vincenzo did what he could as a day laborer to help the family put down roots.

As the years went on, the Quaratiellos welcomed their first child, Anthony, into the world in 1887, followed by another boy, Dan, in 1889. That same year, Vincenzo’s mother Carmela joined the family from Italy, and things seemed to be looking up. A daughter, Carmela Jr., was born in 1893, but tragedy struck the family when she died after only one month. Possibly, two more attempts at bearing children in the 1890s may have had a similar fate.[i] Fortunately, a new century brought new luck to the family. On October 6, 1901, they welcomed their third child, Francesco “Frank” Quaratiello, into the world. The family went on to have at least five other children: Molly (1904–1988), Emily (ca.1905–1987), Joe (1906–1974), Anna (ca.1908–1987), and Ernie (1911–1995).

With eight kids and three generations living in the Quaratiello household, the large family was strapped for resources in a city and country that was usually very unforgiving toward Italian immigrants. Fortunately, the 19th Ward was home to the “Hull House,” a famous Chicago settlement house for all nationalities. Founded by humanitarians Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr, it focused on socializing and community growth as well as the sharing of knowledge and the arts. It boasted a strong music program, and many young boys like Frankie and even Benny Goodman got their musical starts in Hull House bands. In 1911, Quartell picked up the clarinet but soon switched to the cornet. He took lessons from fellow resident James Sylvester, and one of Quartells’s older brothers eventually helped him purchase his first cornet, a silver-plated Lyon and Healey horn, for $25.

While Quartell was discovering music, the city of Chicago was experiencing a musical revolution through an explosion of a new form of syncopated dance music taking the city by storm. Though hot music had existed there since at least the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, in the first 15 years of the twentieth century, out-of-towners like Wilbur Sweatman, the Original Creole Orchestra, Tom Brown’s Band from Dixieland, Jelly Roll Morton, Johnny Stein, and countless others made their mark on the city by introducing a new way of playing it (it’s entertaining to think that the same year Wilbur Sweatman published “Down Home Rag” in Chicago, Quartell played his first notes!) Indeed, some argue Chicago is where the term “jazz music” was coined. It certainly was in use there as early as 1915, when Bert Kelly’s legendary band began using it to signal potential patrons that his brand of music possessed a certain kind of “pep” that set it aside from regular social dance music. What’s not debatable is that a lot was going on musically and that generations of musicians would be swayed by all the goings on. With the “discovery” of another out-of-town band, the Original Dixieland Jass Band, in 1916 by another out-of-town act, Al Jolson, the city’s fate as a center of jazz music was sealed.

Quartell was instantly bitten by the jazz bug, though whether he heard any of those bands early on is unknown. Ray Lopez did sing Quartell’s praises in later years due to his work with the Oriole Terrace Orchestra but didn’t mention anything earlier.[ii] What we do know is that he started a small five-piece band that played for high school dances starting around 1915. Due to Quartell’s October 1901 birthday, he barely missed the 1917 Selective Service Act’s 1917–18 drafts and instead focused on his music and working as a chauffeur.[iii] By 1919, he was officially a card-carrying union musician (by way of the Alma, Michigan union) and briefly joined a small band called the “Kentucky Five” that went to St. Louis, where he played his first major professional show.[iv] The show was a success, and it’s not a stretch to imagine Quartell must have seen something more promising in the stage lights of St. Louis than on the streets of the 19th Ward. Trumpeter Louis Armstrong, who came from a similarly tough background and similarly discovered St. Louis in this era, described the feeling of seeing the city for the first time:

“There was nothing like that in my hometown, and I could not imagine what they were all for. I wanted to ask someone badly, but I was afraid I would be kidded for being so dumb. Finally, when we were going back to our hotel, I got up enough courage to question [bandleader] Fate Marable. ‘What are all those tall buildings? Colleges?’” [v]

At that time, St. Louis boasted some fascinating music, such as the aforementioned Marable band with Armstrong and the earliest version of Charlie Creath’s famed group. That Quartell heard bands like these during this time and incorporated their styles into his own music is certainly a possibility. Quartell appears to have stayed for an indefinite amount of time in St. Louis before returning to Chicago in the mid-spring of 1921, when he deposited his musician’s union card there for the first time.[vi] Incidentally, the guitarist and banjo player Nick Lucas deposited and removed his union card at the same time, in March of 1921. Could this have also been the beginning of his relationship with Quartell?[vii]

The Second Ring: “Dangerous Blues”

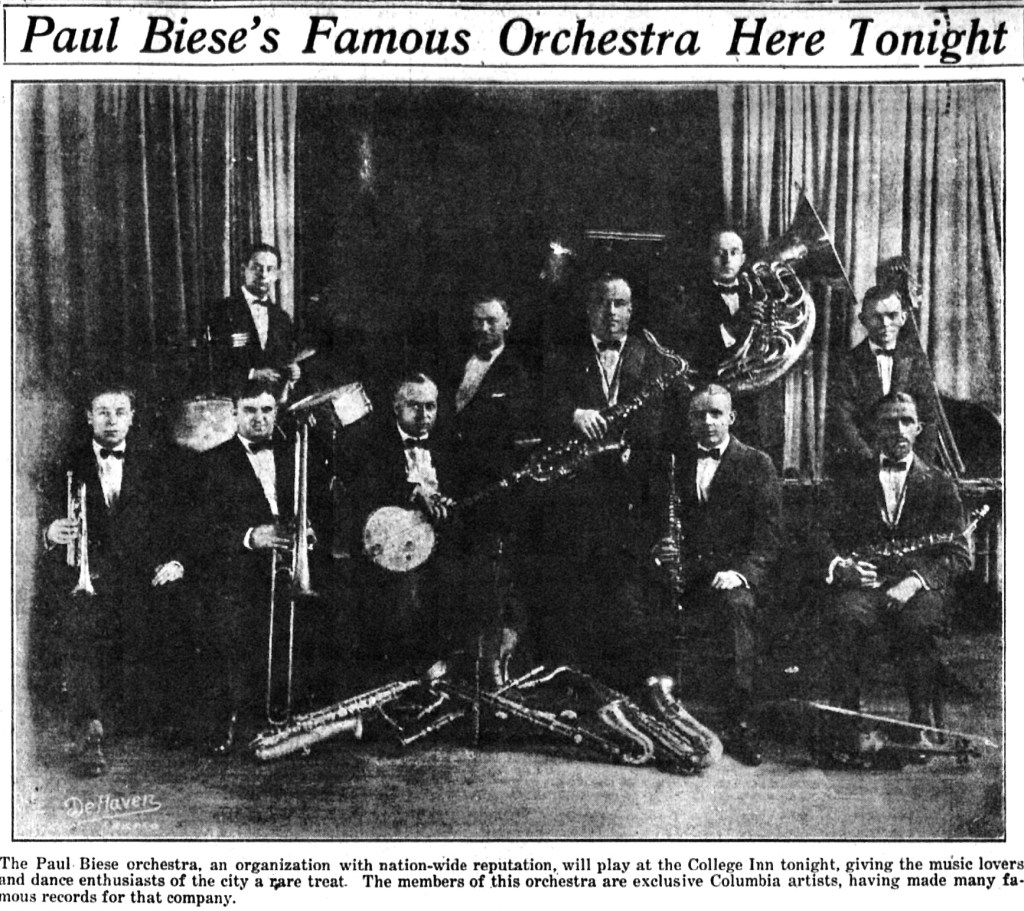

Sometime around March or April of 1921, Quartell was approached by the tenor saxophonist, bandleader, and Columbia Records recording star Paul Biese. Known for his husky presence and even huskier sound, Biese was instrumental in putting the post-ODJB Chicago jazz scene on the map and attracting the attention of several phonograph companies. While leading a successful band at the city’s College Inn, Biese decided he wanted a new lead trumpeter to replace Henry “Rags” Vrooman and likely hired Quartell sometime in April of 1921.

It was with Biese that Quartell, now going by that Americanized version of his last name instead of “Quaratiello,” probably made his first records, likely traveling with the band to New York City in May.[viii] Among these recordings are three beautiful selections backing Marion Harris where what sounds like Quartell’s distinctively raspy and quavering tone can be heard. However, he is featured very little otherwise. The band’s instrumental sides aren’t much better, though it certainly sounds like he is leading the band on their June recording of “Crooning.” To me, the most obvious candidates are the several sides cut with Biese’s trio, where an unnamed cornetist possessing the same tone and a knack for mutes contributes many fine obbligatos and even a gorgeous open horn solo of the melody of “Sweet Love” interpolated into the Biese recording of “Dangerous Blues.” This four-piece “trio” also backed singer Frank Crumit on some great sides, including a particularly bluesy rendition of “Frankie and Johnny” (incidentally a St. Louis tune.)

In later years, Quartell recalled staying with the band for about six months, substantiated by a clipping in the July 1926 issue of Radio Digest. Given that he is photographed and mentioned as being with the band as late as November of 1921, by the end of the year, his tenure with the band appears to have been complete.

The Third Ring: “Oriole Blues”

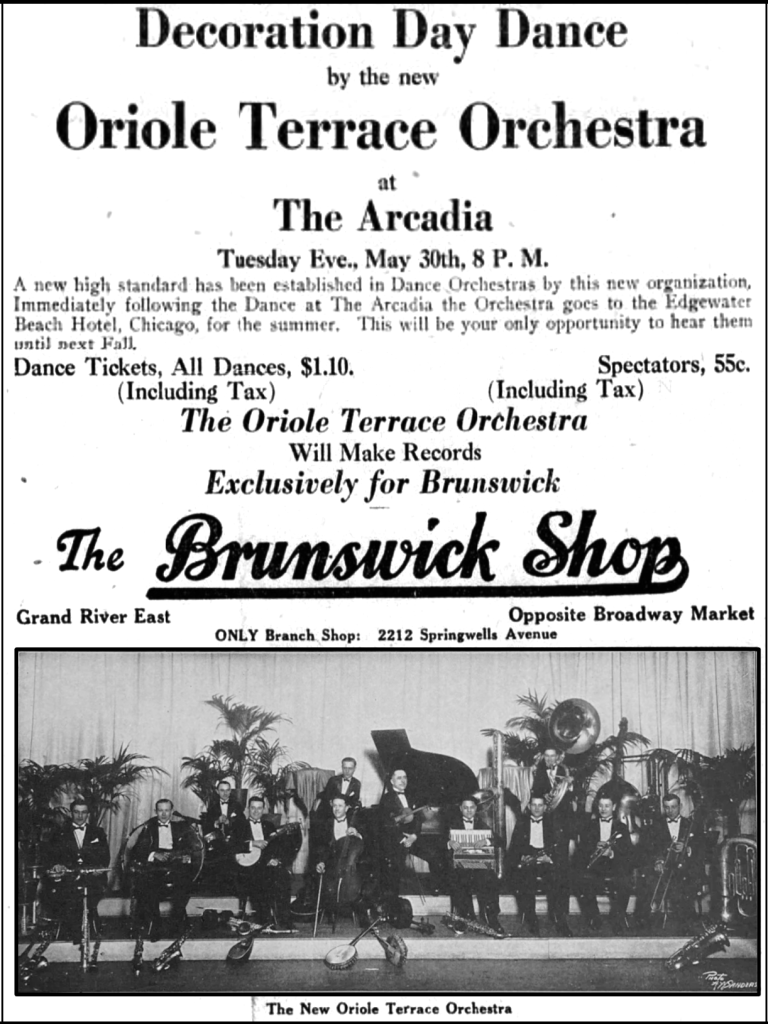

In May of 1922, Quartell boarded a train from Chicago headed to New York City. He had been hand-picked by the proprietors of the brand-new Oriole Terrace Ballroom in Detroit and by Gus Haenschen, head A&R man of Brunswick Records, to play hot cornet in a new ensemble that the ballroom and company were putting together: the Oriole Terrace Orchestra. Touted as the “greatest orchestral combination in America,” being “composed of jazz experts from the levees and Chicago,” and “12 jazz mad musicians from the nifty home of jazz,” the band’s personnel was indeed a mix of musicians from cities such as Chicago, New Orleans, and Kansas City, all major influences on the development of jazz. The dozen-piece unit possessed a dreamy sound, with such talents as pianist Ted Fiorito, violinist Dan Russo, lead trumpeter Marty Campbell, New Orleans-born trombonist Roy Maxon, ex-Kansas City accordionist Frank Papilla, saxophonist Clayton Nassett, and later on Nick Lucas, who may have begun recording with the band as early as September of 1922 before joining them full time the following year. In between beautiful sonorities from the reeds, accordion, and strings, the sound was punctuated by hot muted breaks and choruses from Quartell and Maxon, such as on their recordings of “Oriole Blues” and the phenomenal “Serenade Blues.” The whole thing was supported by a steady and sweeping rhythm section. The band’s first gig appears not to have been a gig at all but their first recording session![ix]

After several days of rehearsals and recording, the band played their first show at the Detroit Arcadia Ballroom on May 30, 1922.[x] Their records became instantly popular, and they quickly secured a contract for a summer engagement at Chicago’s Edgewater Beach hotel, which really became their home base for the next several years despite the Oriole name (they would eventually drop “terrace”). They continued routine trips back to New York to record for Brunswick as well, cutting many fantastic features for Quartell, including “Toot Toot Tootsie,” “Bee’s Knees,” and “Carolina in the Morning,” which Quartell falsely recalled as the first record to feature a “wah-wah” mute sound.

(Author’s note: David Sager and I have concluded that this was likely done by another Chicagoan, Louis Panico, on “Wabash Blues” with Isham Jones’s Orchestra in 1921, also for Brunswick. Of course, the “wah-wah” effect had existed in jazz going back to Buddy Bolden, but that’s a conversation for another time.)

All of the positive attention earned the band a great reputation that slowly worked its way all the way up to the nation’s top bandleaders, including Paul Whiteman. In January of 1923, the band had its first public appearance in New York City at the B. F. Keith Palace. It was a huge success, and Whiteman, who was in attendance, was floored.

Over the next few months, Quartell’s relationship with the Oriole Orchestra seems to have started fizzling. The Oriole Orchestra played a long engagement in St. Louis that spring, during which he and Frank Papilla also moonlighted with the Maxwell Goldman Orchestra. This was followed by a three-month stay in Cleveland, during which Quartell also joined up with the Vernon-Owens Hotel Winton Orchestra. Though he is present on the recordings the Oriole band made in May, it seems that by that summer, Quartell had left the band, at least on stage.[xi]

The Fourth Ring: “You Should Have Told Me”

Around August of 1923, Quartell and Maxon were both offered positions in Paul Whiteman’s band, which Quartell recounted:

“Now, I had an offer from Paul Whiteman in [1923]. I went to New York, I made a recording with him, but he didn’t offer me enough money to stay with his band. Mr. Gus [Haenschen], recording manager for Brunswick Records, asked me if I would like to go back to the Edgewater Beach Hotel with Bennie Krueger for more money, and I did. I didn’t accept Mr. Whiteman’s offer. I came into Chicago with Bennie Krueger, I made several recordings for Brunswick, and I came to the Edgewater Beach Hotel.”

It seems that this recording must have been either the September 20 or 26, 1923 session, given that Maxon’s first confirmed appearance was September 20. The most likely candidate for this recording is “Cut Yourself a Piece of Cake” from that date, which features two cornets in a muted “wah-wah” chorus, presumably Quartell and the orchestra’s regular lead trumpeter, Henry Busse, who is prominent on the other recording from that day, “I Love You.” However, it is quite difficult to tell whether or not Quartell is truly present. Whatever the case, by October of 1923, Quartell was back in Chicago with Krueger at the Edgewater Beach Hotel, likely thanks to Haenschen and Brunswick’s relationship with both the band and the venue.

In early 1924, Quartell traveled again, this time for a brief stint with bandleader Arnold Johnson in Miami alongside fellow Chicagoan Vic Berton. He also began working with the pianist Art Kahn around this time, possibly thanks to his relationship with Berton (a member of Kahn’s Columbia recording orchestra) that went back to the Paul Biese days. It’s not known if Quartell recorded with them at this time (it may be him contributing the hot derby muted solo on “Bahama”), but he would certainly record with them later in 1924 and on the band’s January 1925 sessions. He is particularly well-featured on “You Should Have Told Me” and “Insufficient Sweetie,” the former a fast-paced romp featuring his “dicty” straight lead style and hot improvisations and the latter a low-down affair.

In between Johnson and Kahn, Quartell found his way back to New York again to play with bandleader Paul Specht. Replacing Italian-born trumpet player Frank Guarente, Quartell spent much of the summer with Specht, recording many great sides for Columbia, including a lovely blues waltz entitled “Come Back to Me,” his most beautiful performance on record to date. At the end of this engagement, he took a brief vacation to Wisconsin, where he played with Frank Doyle’s Orchestra in Green Bay.[xii]

The Fifth Ring: The Melody Boys, Isham Jones, and the Mid-20s

The mid-1920s were good to Quartell. Returning to Chicago in the fall of 1924, he began fronting his own band for the first time since joining Paul Biese. Likely road-weary and ready to take a break from being a sideman, he organized “Frankie Quartell and His Melody Boys.” Before long, the band was quickly engaged at the city’s Montmartre Café, the revamped Green Mill Gardens, where the Chicago Cellar Boys and many other groups still hold court to this day. Although his usual reedmen were Al Hyatt, Dave Sholden, and Maurice Morris (how’s that for a name!?), around this time, Quartell also briefly employed Benny Goodman, though the venue made him fire the young clarinetist for his “unconventional” style. I guess they weren’t ready for the sounds coming out of Hull House.

The Melody Boys recorded two sides for the General Phonograph Corporation’s Okeh Records in December of 1924: “Prince of Wails” (which this article begins with) and the even stranger “Heart Broken Strain.” Both feature Quartell’s lead and distinctive mute work, very much up-to-date for late 1924. The rest of the band isn’t quite as tight, although the final chorus of “Prince of Wails” is fantastic, particularly thanks to Morris’ slap tongue saxophone work. Hyatt’s sour clarinet work leaves much to be desired, though some phrases are hip.

In early 1925, Quartell was once again compelled to work as a sideman when he received an offer from Isham Jones to replace Louis Panico as the hot cornetist in his band. Three years Panico’s junior, Quartell was quite similar in style and approach to Panico and was a logical choice. Further, his skills as a veteran recording artist only made him more attractive to the business-minded Jones. Quartell contributed many fine solos to the band’s mid-1920s Brunswick records and even traveled with them to the United Kingdom in 1925 to play the Kit Kat Club, replacing Ted Lewis and Vincent Lopez before that.[xiii] His playing on the band’s “River Boat Shuffle,” “Danger,” “Sweet Man,” and “The Original Charleston” are among the cornetist’s finest recordings.

(Author’s note: One of the more entertaining stories (to me at least…) relating to this era of Quartell’s life was a mix-up I made between Quartell and Frank Cotterell (1903–1940), who Wolverines authority Chris Barry helped explain was another Chicago trumpeter and reedman who preceded Bix Beiderbecke in the Wolverines, and probably is the guy present on the Dudley Mecum’s Wolverines tests for Paramount in fall of 1925, as opposed Quartell, who was either about to leave for Europe with Isham Jones or was already en route!)

After his tenure with Jones, Quartell briefly returned to the Edgewater Beach Hotel in 1926, where he performed with the new Edgewater Beach Hotel Orchestra fronted by violinist Joe Gallicio and directed by pianist Roy Bargy. During this stint, he traveled with the band to play a Kentucky Derby overnight excursion train, which pulled over in French Lick, Indiana, to let patrons use the town’s gambling establishments. During the trip, Quartell had a most interesting conversation with Mr. S. G. Gonzalez of El Paso, Texas, who was a passenger on the train. During the discussion, Quartell recounted that:

“Mr. Gonzalez said, ‘If you ever decide to come to El Paso, I own the Central Cafe in Judrez, Old Mexico, and would like to have you work for me as my orchestra leader.’”[xiv]

Though he did not initially take up Gonzalez, this exchange would change Quartell’s life in later years.

Returning to Chicago, Quartell briefly rejoined his fellow Hull House alum Benny Goodman, this time as a member of Ben Pollack’s famed band, where he contributed some second cornet work to such jazz classics as “Waitin’ for Katie.” Sadly, Quartell is virtually indistinguishable on this lauded recording, but his presence only adds to the magic.

The Sixth Ring: “Way Out West in Texas” and “Way Down ‘Yonder in New Orleans”

In 1927, Quartell founded a new band at the Club Mirador in Chicago that achieved some success. However, it seems Quartell fell in with the wrong crowd at this time as he picked up a bad habit of gambling that eventually led to a nasty separation from his wife, Arvilla.[xv] In the wake of all of this drama, Quartell wanted to get away, and that opportunity soon arrived at the behest of Texas gangster Sam Maceo, who offered Quartell a chance to play a season at the Grotto in Galveston, Texas, a well-known nightclub and gambling casino in that gulf-side city.[xvi] Maceo was an interesting character who rented a suite of rooms in the palatial Hotel Galvez and traveled annually to New York to buy the latest white suits specially tailored for him.

Hiring a band that included Quartell’s brother Joe on trombone, this group was quite popular and generally a good experience for Quartell. He fondly recalled hanging around Galveston Island’s speakeasies and red-light districts as well as at the Hotel Galvez, where he also took up temporary residence and where bandleader Dandy Wellington now leads Jazz Age-style bands at an annual summer soiree.

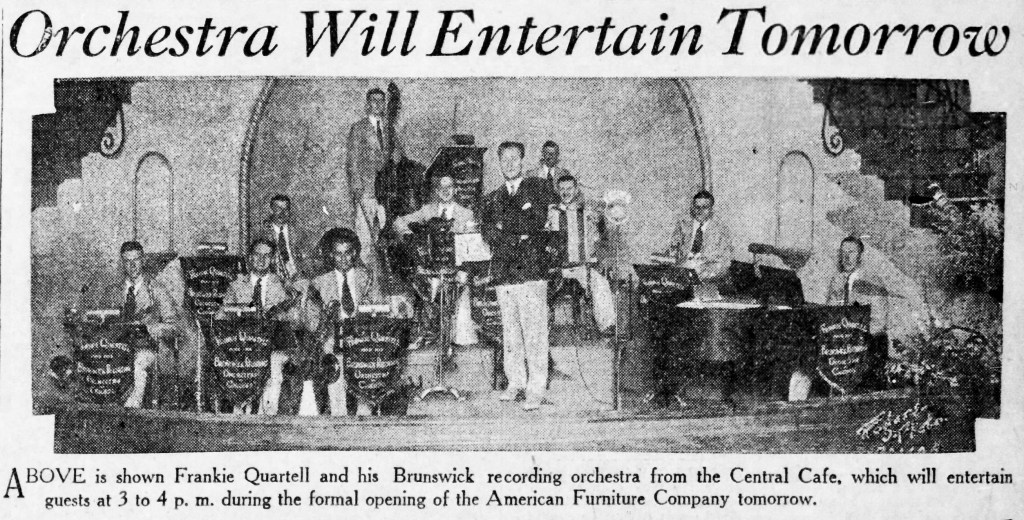

Following the Grotto engagement, Quartell played a short stint at the Little Club in New Orleans, Louisiana. While there, his band recorded two sides for Brunswick Records, who were on a field trip through the American South to record local talent for local markets. “Sweet Baby” and “Pining,” the two recordings the Quartell Little Club Orchestra waxed, are stylistically quite different from his 1924 recordings, focusing more on rhythmic heat than oddball arrangements. What is consistent, however, is Quartell’s raspy and driving lead tone that shines through on both sides. Unfortunately, the Little Club engagement ended early due to unsatisfied management, resulting in an early departure from New Orleans and a lawsuit from Quartell.[xvii]

Traveling back to Chicago in early 1929, Quartell found work at the Beaumont Club and recorded a couple of sides with Nick Lucas, including the Spikes Brothers’ latest “Someday Sweetheart” knockoff, “Some Rainy Day.” He longed for the road again and booked his band for engagements in Cleveland, Los Angeles, New York, and a six-week engagement at the El Tivoli nightclub in Dallas. During this gig, he began to recall his run-in with Mr. Gonzalez during the Kentucky Derby excursion three years earlier and figured he’d see for himself if it was true. Further, he had recently discovered that his wife had contracted tuberculosis, which a dry climate would help cull. Boarding a Texas and Pacific train, he headed for the border town of El Paso with little more than Gonzalez’s name and address.

The Seventh Ring: “The Voice of the Rio Grande”

Despite its remote location, in the 1920s and 30s, El Paso boasted many fine bands and jazz musicians like the Doc Ross orchestra with Wingy Manone and Jack Teagarden and Dallas trombonist Bert Johnson’s Sharps and Flats, which included a young Don Byas and Milt Hinton as well as Ida Cox on vocals. Its location across the border from Mexico also meant that it was in close proximity to vices that were still illegal in the United States, including alcohol. As such, clubs across the river in Juarez offered steady work for musicians without the competition of larger scenes. Given that Quartell had been working professionally for over a decade and with the nation’s top bandleaders for eight years, it makes perfect sense that El Paso was an attractive option to the trumpeter from a work standpoint.

After locating Mr. Gonzalez, Quartell set up an international band of American and Mexican musicians at the Central Café in Juarez. A trio from the larger band (likely Quartell and the group’s two other American musicians) began broadcasting from the radio station WDAH, “The Voice of the Rio Grande,” on the roof of the El Paso Del Norte Hotel that still stands.[xviii] Quartell recalled that the amateur station only paid the band a weekly salary of $15.00 (only about $285 in today’s money) for daily half-hour shows six days a week![xix] Quartell functioned as emcee, bandleader, soloist, and vocalist, singing his theme, “The Bouncing Baby.” Through these broadcasts and performances, Quartell became the most popular musician in the city and achieved a decent amount of wealth. By the fall of 1929, he was even able to open “Frankie Quartell’s Music Shop” that sold Brunswick records, radios, and instruments.

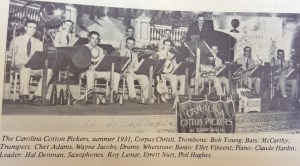

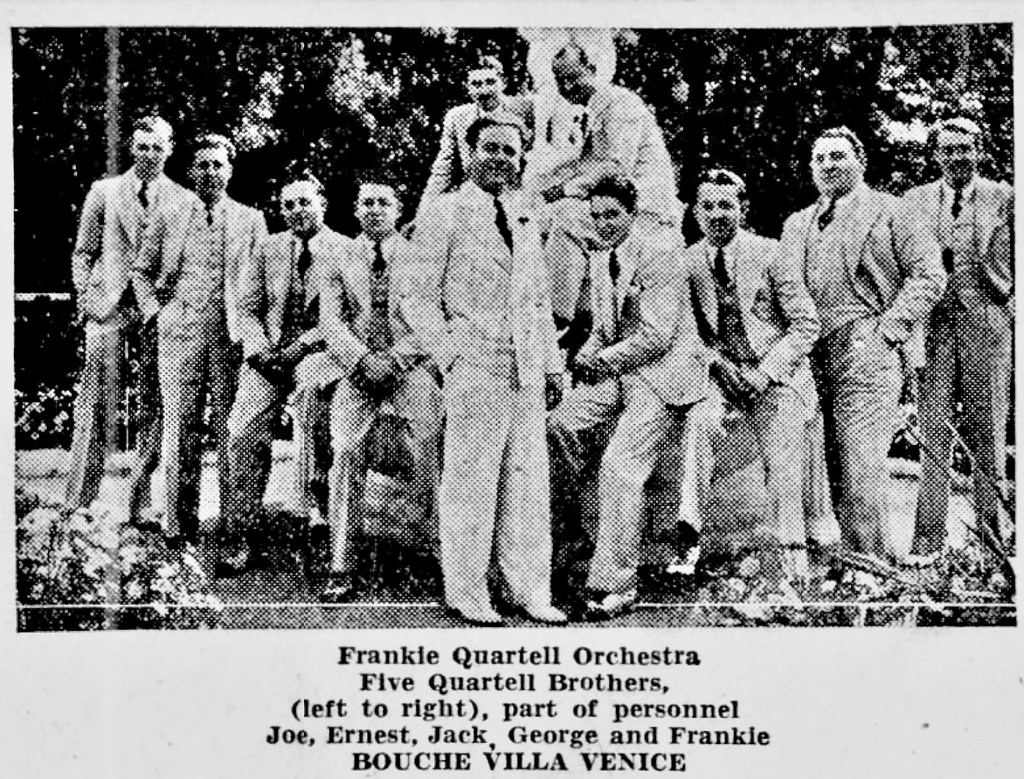

Despite the difficulties of the stock market crash, Quartell hustled even more to find steady work through much of the 1930s. Leaving El Paso and his shop due to the Depression, he ended up back in Chicago leading a band called the “Playmates” at the Edgewater Beach Hotel back in Chicago before relocating to the city’s Villa Venice.[xx] He continued playing around Chicago but routinely brought bands back to Texas, including shows in Galveston and Corpus Christi in 1932.[xxi] In 1934, the band traveled to Miami to play New Year’s Eve at the city’s own Bouche Villa Venice. The band also featured his brothers Joe, Ernest, Jack, and George, billed as the “Five Quartell Brothers,” a hot band within the band.[xxii] This, combined with the venue’s other acts, turned into a steady review that was so popular that the band was brought down to Cuba to play the Teatro Nacional in Habana, one of Quartell’s proudest moments and one of the farthest excursions music would take him on..[xxiii]

The Eighth Ring: Later Years and Epilogue

As the Great Depression wore on, Quartell began struggling to find work. He became a sideman again when, in 1936, he reconnected with his old Oriole Orchestra pal Nick Lucas to play a brief stint at New York’s Hollywood Dinner Club and (briefly) marrying 19-year-old Virginia Lee Chew. Relocating to Chicago once more, he led another band that played throughout the Midwest and was based at Colosimo’s café. This band had a steady engagement for a few years and was one of the longest tenures Quartell had in one place. It seemed that years on the road had finally caught up with him.

In 1942, just as World War II began for the United States, Quartell enlisted in the U.S. Air Force. Like so many other musicians who served, he was involved in music leadership, conducting the Air Force Training Command band at the Stevens Hotel in his hometown of Chicago. In between this, he also managed to manage the city’s Morocco Theatre Café until the war ended. In classic Quartell fashion, he was ready to move once again, this time to Los Angeles, where he became manager of the city’s Stowaway Room. Evidently, this didn’t last long. By the early 1950s, he moved back first to Chicago, where he married his last wife, Lois Zuber, and then to Florida, where he managed the Colonnade Hotel auditorium in Riviera Beach. But something in him once again called him back to El Paso, where he eventually retired for good, convincing much of his family to move there in the process. He spent the last two and a half decades of his life there, enjoying the sunshine and fond memories of the days when he was the city’s musical kingpin. It was there that he would eventually pass away on August 22, 1984.

Frankie Quartell’s life story is unique. Like a pinball, he bounced around the country and, indeed, the world during some of the most economically challenging times in American history. Raised from almost nothing, he worked his way into the national spotlight and made an impact nearly everywhere he went. But, like the music he loved, he faded into obscurity with the changing of the tide, and so too did much of his legacy. But thanks to a few scratchy old records, some faded newspaper clippings, and the tireless love of jazz fans from around the world, we can rediscover and revive the legend of Frankie Quartell and the music that captured audiences from the Hull House to Havana one side (or tree ring) at a time.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Dave Bock, Kevin Coffey, Ate Van Delden, Vince Giordano, Javier Soria Laso, David Sager, Andrew J. Sammut, and Dustin Wittman for their help in preparing this article and providing precious source materials including recordings, clippings, and photographs.

Thanks to Kevin Coffey and Andrew J. Sammut for their careful edits to this piece. Thanks also to Coffey for his help with establishing an accurate timeline of the Oriole Orchestra. Thanks to Sammut for inclusion of this piece on his Pop of Yestercentury blog.

Thanks to Dustin Wittman for his restorations of “Prince of Wails,” “Sweet Baby,” and “Pining.”

Personnel and discographical information taken from Brian Rust’s Jazz and Ragtime Records, 1897–1942 and The American Dance Band Discography, 1917–1942; Richard J. Johnson and Bernard H. Shirley’s American Dance Bands on Records and Film, 1915–1942; and the Discography of American Historical Recordings with edits, additions, and revisions by Kevin Coffey, Javier Soria Laso, and Colin Hancock.

Endnotes

[i] A birth certificate for Maria Carmela, born July 4, 1894, to Vincenzo and Crestina, exists in the Cook County records but no records appear to exist after that besides an 1896 New York State death certificate that lists Maria Carmela to have been born in 1895 yet is unconfirmed as to whether or not the parents are Vincenzo and Crestina. Another Carmela, aged one and born in 1898, is listed in the 1900 census as a daughter living at the Quaratiello household beneath her grandmother, Carmela Sr. Could this one-year-old be the same as the ca. 1894 Carmela? Could she have been yet another premature death in the family. So far, we do not know.

[ii] Dick Holbrook: “Mr. Jazz Himself: Interview with Ray Lopez, Part II,” Storyville no. 69 (1977)

[iii] In his 1977 interview, Quartell claimed to join the Kentucky Five in 1918. Though there is a Kentucky Five performing in St. Louis in 1918 with the Zeigler Sisters, Kevin Coffey pointed out that it’s unlikely that Quartell would have traveled this early before being a card-carrying union musician. Quartell also misremembered his dates by about two years in the interview (stating, for instance, that he joined the Oriole Orchestra in 1920 rather than the actual date of 1922), which would place his tenure with the Kentucky Five closer to 1920–21.

[iv] 1977 UTEP interview; research by Kevin Coffey.

[v] Kennedy, William Howard: Jazz on the River, chapter 3: Louis Armstrong and Riverboat Culture.” University of Chicago Press, 2005, p. 66.

[vi] Research by Kevin Coffey.

[vii] Id.

[viii] Contemporary advertisements for the band specified that each musician was a “exclusive Columbia recording artist.” Judging by the frequency that Biese recorded at this time, aural evidence on the recordings, and photo evidence, Quartell’s presence is almost without question.

[ix] “Fine Dance Hall is to Displace Theatre,” Detroit Free Press, May 7, 1922, p. 45; The Brooklyn Daily Times, Jan 7, 1923, p.16; Brooklyn Eagle, Jan 7, 1923, p.36.

[x] “Arcadia Closes Tonight with Wonder Orchestra,” Detroit Free Press, May 30, 1922, p.1.

[xi] Research by Kevin Coffey. Though Quartell claimed to have been in the band “a year and a half,” Kevin Coffey points out that contemporary press for the Oriole Orchestra stop mentioning Quartell (but keep mentioning Papilla, Lucas, etc.) around June of 1923. Could Quartell have just stayed on for the recording sessions after the Cleveland engagement? It is also worth noting that though the Vernon-Owens band did make records for Gennett that year, their recordings were made in February, and therefore Quartell’s presence is doubtful

[xii] Research by Kevin Coffey.

[xiii]Id.

[xiv] 1977 UTEP interview.

[xv] “Stinting Wife to Play Poker Wrong Court Says,” The St. Louis Star and Times, Feb. 28, 1927, p.3.

[xvi] 1977 UTEP interview.

[xvii] Research by Kevin Coffey.

[xviii] Id.

[xix] Id.

[xx] Brooklyn Eagle, Feb. 14, 1930, p.2; 1977 UTEP interview.

[xxi] “Noted Dance Band to Play Here Friday!” Corpus Christi Times, May 23, 1932, p.3.

[xxii] “Appearing at Metropolitan Miami Supper Clubs,” The Miami Herald, Feb. 23, 1935, p.12.

[xxiii] “Villa Venice Open Until End of the Month,” The Miami Herald, Mar. 23, 1935, p.28.

[Thanks so much to Colin for sharing his post here!—AJS]