It’s no surprise that yestercentury’s verdicts on jazz included plenty of praise and lots of bile. New music always gets the same criticisms: lacking quality, spreading immorality, derivative of older music, and a lot of racist claims ranging from veiled to brazen but uniformly disgusting. Yet as jazz spread across the United States and the world, some voices took a middle ground. For them, jazz wasn’t worth the venom. It was neither great music nor a threat. It was harmless fun, but jazz still served an important purpose: helping people appreciate music deemed better than jazz.

One writer spelled out jazz’s edificatory potential in the June 15, 1924, issue of Talking Machine World. Profiling bandleader Henri Berchman, the reporter described a “modern dance orchestra” that took pride in playing both popular and classical works. This band appealed to audiences who were “interested in real popular music and, at the same time, have an inborn taste for better things.” These “better-class orchestras” would “lead those of strictly popular taste into an appreciation of the classical.”

At least jazz haters assumed the music had some power; people don’t mourn the loss of artistic standards or forecast the downfall of civilization unless they perceive a threat. This didactic assessment of jazz doesn’t even give the music that much credit. Jazz is not a threat; it’s homeopathic music appreciation. Judgments like these seem more surprising for their effortless condescension.

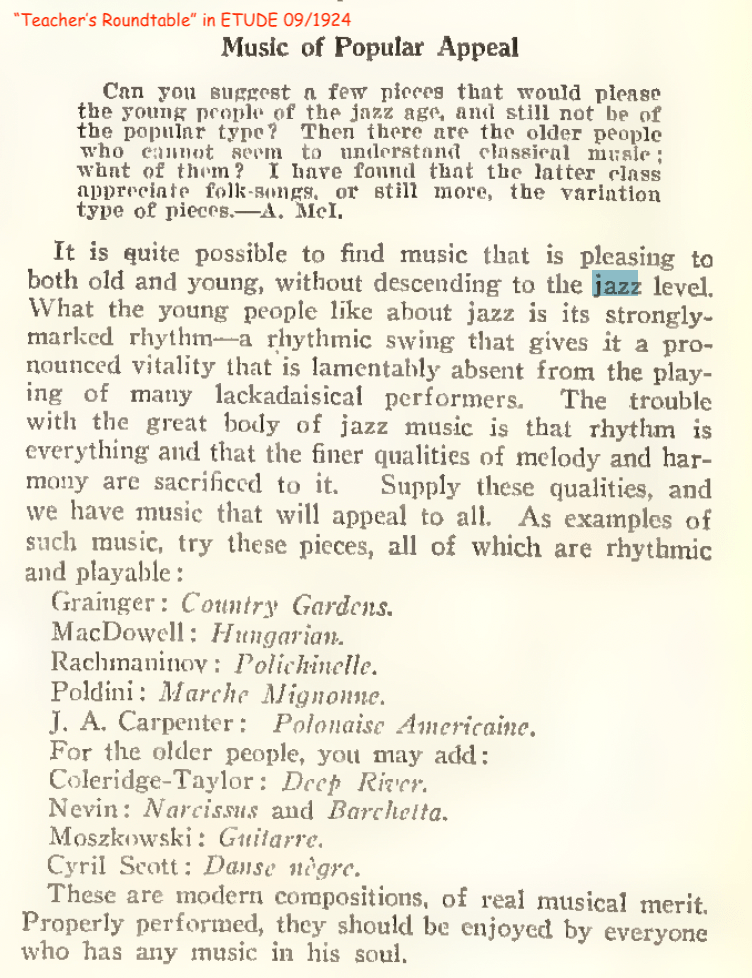

The August 1924 issue of Etude magazine, dedicated to “The Jazz Problem,” is like a compendium of contemporary outlooks on jazz. Its descriptions ranged from music for a country that lost its soul to conductor Leopold Stokowski hearing jazz as “new blood [flowing] in the veins of music.” Ironically, Paul Specht, one of the most popular bandleaders of the time, neatly summarizes jazz apologetics:

This form of music is a forceful stepping stone to stimulate interest in the study of music; a step of musical development, distinctly American, that is teaching the public to better appreciate our big symphony orchestras.

Paul Whiteman takes the perspective a step further, suggesting his music opens audiences to other pieces of high culture:

We cannot expect the man in the street, with a Police Gazette in his hands, to pay a large price to see Ibsen’s Ghosts. He must be educated up to Ghosts. He will be fascinated by jazz and use it as a suspension bridge to better things.

Whiteman was one of the most successful popular musicians in American history. He also frequently defended popular taste. In his book Jazz, Whiteman makes a lengthy point about good taste and popular demand not being mutually exclusive, insisting that “the so-called masses have considerable instinctive good judgment in matters of beauty that they never get credit for.” He’s also skeptical, almost resentful, of “certain high and mighty art circles.” Whiteman advises that “the Denver [Whiteman’s hometown] boys who haven’t grown up to conduct orchestras and police reporters who haven’t got jobs as critics have sound opinions, too, and we ought to listen to them.”

It’s not that strange to hear Specht and Whiteman advocate for their music as a path to high art. They were key players in the growing popularity of jazz-influenced dance bands. They also saw these bands and their arrangements grow in size and complexity. Specht, Whiteman, and other bandleaders probably just understood which elements of their music might appeal to the elitists. They didn’t make music to pander to longhairs, but creative pursuits and marketing sometimes align.

Some members of the musical establishment found symphonic jazz and imaginative “special” arrangements promising. Composer and critic George Hahn heard the development of bigger bands and more sophisticated arrangements as jazz finally “being done artistically.” In his essay “Modern Arrangers Are Synthetic Composers” (Jacobs’ Band Monthly, September 1923), Hahn notes how “the erstwhile blatant jazz has given way to smoothly flowing, beautifully voiced harmony and rhythm” thanks to “arrangers and directors who took the raw jazz as it came from New Orleans and change[d] it into the aristocratic variety we have today.”

Hahn thought jazz could redeem itself through advanced compositional techniques and curbing improvisation. Others still heard a means to a higher end. In his essay for Etude, composer Percy Grainger compliments jazz for advances in instrumentation comparable to those of Beethoven and Wagner. Grainger goes as far as describing jazz as “near-perfect and delightful popular music and dance music.” Like all dance music, it provides excitement, relaxation, and sentimental appeal.

Grainger’s description might seem like one of the more charitable ones. Yet alongside his confusing, borderline offensive pseudo-ethnomusicology (i.e., jazz as the “combination of Nordic melodiousness with Negro tribal rhythmic polyphony”), he declares jazz some of the “finest” popular music in history but “nothing more.” Grainger comes off as pompous rather than antagonistic, and more insulting for it:

The laws which govern jazz and other popular music can never govern music of the greatest depth or the greatest importance…The world must have popular music…But there will always exist between the best popular music and classical music that same distinction that there is between a perfect farmhouse and a perfect cathedral.

To Grainger, popular music doesn’t make demands on the listener, while classical music demands “length and the ability to handle complicated music,” signs of superior intelligence. He allows that jazz can help educate children, but parents and educators must ensure youngsters also “drink the pure water of the classical and romantic springs.”

This is praise with damning consequences. Grainger consigns jazz to (at best) an educational role, while remaining a diversion for simple minds. If any adults are listening to jazz, they’re free to enjoy the farmhouse, but they only get to Heaven if they can find their way to the church. The imagery of purity—presumably versus dilution or even pollution—feels especially ironic from a composer known for experimental music that explicitly rejected traditional classical structures and his pioneering role in folk music revival.

These are just a few examples, and they were less prevalent than outright condemnation, but arguments for jazz as classical music’s training wheels emerged often enough. They form a unique corner of the early reception of jazz. They share the same focus on cultural hierarchies as the outright condemnations. Still, their patronizing equivocation lets some music squeak through, music that people who heard Ted Lewis and Paul Whiteman as equally hateworthy would never allow.

It’s no accident this line of thought coalesced around a lot of music many now consider at the margins or completely beyond jazz. The overwhelmingly white composition of jazz commentators at the time will either seem predictably offensive or still shockingly ignorant. The word “jazz” covered a lot of musical and cultural ground during the twenties. Yet whether it was Duke Ellington, Paul Whiteman, Joe Oliver, or Earle Oliver, the harshest critics seemed to be battling for the country’s soul. This high-handed middle ground seemed to be waging a cold war for America’s brain. Neither campaign was needed. At least judging people based on their taste is a last-century problem.