At least by the time of his sixth musical, Jerome Kern was no fan of jazz. According to the “Melody Mart” column in the April 26, 1924, issue of Billboard magazine, jazz drove the Broadway composer to bar publishers from printing orchestrations of songs from Sitting Pretty, Kern’s newest show.

It was partially an economic decision. Sheet music, record, and theater sales were crashing. Many blamed radio for offering too much free music. Audiences supposedly got sick of the latest songs too soon. With Kern’s embargo, the only place to hear numbers like “Shufflin’ Sam” and “Bongo on the Congo” as envisioned for the stage would be the stage. In theory, demand at the box office, record shop, and your local sheet music seller would shoot up.

Yet this was about more than the bottom line. Kern was a composer as well as a businessman. He wanted his music performed as he wrote it:

By keeping his numbers away from jazz leaders, who mutilate the music, sheet music sales of the show numbers will be fair enough due to the patron who hears them in the production … [Kern] was against the jazz orchestras butchering a song so that the public never knew what it really was … There was no way to prevent the so-called special arrangements being made by phonograph record artists who wanted and had to be different.

People could buy lead sheets with lyrics and piano accompaniment, but jazz musicians wouldn’t find stock arrangements waiting to be mangled with their improvisations and slick effects.

Discouraging musicians from following their creative instincts, demanding they stick to a written part, privileging published composition over bandstand invention: It might be the triumph of crass commercialism and mass culture over artistry. Yet it might also reflect something less cynical and much simpler, a musical ideal as common in the 1920s as the 2020s, something that proud songwriters and the average Jazz Age music consumer could both agree on: hearing a tune.

Supply and Demand, Creativity and Taste

Kern and his fellow songwriters considered themselves artists, too. They also wanted to create music for audiences to enjoy. Jazz blogger (and my dear friend) Michael Steinman points to Richard Rodgers and lyricist Lorenz Hart making their demand literal and singable in “I Like to Recognize the Tune.” In his autobiography, Rodgers elaborates on the philosophy behind the song’s pointed title:

We voiced objection to the musical distortions then so much a part of pop music because of the swing band influence. We really had nothing against swing bands per se, but as songwriters, we felt it was tough enough for new numbers to catch on as written without being subjected to all kinds of interpretive manhandling that obscured their melodies and lyrics. To me, this was the musical equivalent of bad grammar. On the other hand, once a song has become established, I see nothing wrong with taking certain liberties. A singer or an orchestra can add a distinctive, personal touch that actually contributes to a song’s longevity. I can’t say I’m exactly grief-stricken when something I’ve written years before suddenly catches on again because of a new interpretation.

Popular musical styles had changed by the time the song was published in 1939, but the sentiment remained evergreen. The difference was that many American popular standards were not yet “established” during the twenties. Songwriters at the time might’ve felt like an author watching a film version of the novel they just got published.

Tin Pan Alley was a huge commercial complex. An entire industry of composers and lyricists supplied romantic songs, dance numbers, novelty tunes, topical ditties, and anything else people could sing, dance, relax, laugh, neck, or cry to. But the music industry was also a creative site. Some people worked hard and took pride in their product—even if it also allowed them to pay rent or buy a second Packard.

On the other side of supply, there was demand from audiences, who weren’t looking to make anyone rich. Some just wanted good lyrics set to a catchy melody. Others were more discerning. Both reflected preference for song.

Ironically, by the beginning of the Jazz Age, many dancers and listeners wearied of wild improvisations and careening ensemble lines that obscured the tune (while, of course, many others couldn’t get enough). By December 1921, Dance Review reported that “artistic, refined effects” and “carefully worked out novelty choruses” were already overshadowing “loud ‘jazzy’ playing.” William Howland Kenney points to one editorial, titled “The First Fight on Jazz” in the New York Clipper of August 16, 1922, that captures the outcry for a clear tune:

A popular tune is played by one of the jazz orchestras. The orchestration for it has been furnished by the publisher at a considerable cost, but as rendered by many of the orchestras, few that had heard it in the song form or played on the piano would recognize it … A well-written melodious number is so buried under the jazz antics [emphasis mine]…the audience can scarcely recognize the melody.

Popular tastes constantly change, yet this trend was toward the status quo: a solid tune. The frantic counterpoint associated with the Original Dixieland Jazz Band and its imitators was already out of fashion when Kern issued his edict. Large dance bands with brass, reed, and rhythm sections using written arrangements became popular. By November 1926, Orchestra World was covering Tom DeRose’s five-piece New Orleans Jazz Band as a throwback to “good old Dixieland-style jazz” that still played “the more barbaric type of syncopation.” The five-piece ODJB took the country by storm only a little over a decade earlier, a lifetime in American popular music.

Pragmatic music industry officials also had a stake in a solid tune. David Jasen describes this as an era when a song’s publication was more important than its performance by a particular artist. A song was successful if it sold sheet music and records. Several bands might record the same tune for different record labels. Music lovers might buy any recording they could get; they just wanted to hear the song. Yet, as Kenney notes, “jazz polyphonies even endangered the well-established musical arrangements that turned out hit melodies.” He meant more than arrangements on stave paper:

Record companies paid royalties to the sheet-music publishers whenever they issued a recording of a published song. According to Variety, recording company studio managers kept lists of numbers they wanted to record and invariably passed the list first to “the[ir] premier orchestra” which picked all the “hit numbers, that is, tunes that had already sold exceptionally well in sheet-music form.”

A complex industry thrived on literally selling songs. To business stakeholders, if the public was paying attention to a band, they weren’t necessarily focused on the tune. Following that band’s gigs or buying every record they cut didn’t necessarily yield the publisher any direct royalties.

With recording companies eager to keep their slice of the market, business interests viewed bands as vehicles for their tune (not the other way around). Studio ensembles proliferated: house bands and musicians contracted specifically for record sessions, recording Tin Pan Alley’s constant output, often steered in more conservative musical directions.

These may sound like suboptimal conditions for jazz or any form of personal creativity. Yet musicians don’t stop being creative when they read (or write) music. So-called commercial musicians came up with some clever, if sometimes ultra-subtle, musical ideas. The alleged constraints inspired some inventive music.

Variation Through a Theme

If you have to repeat a melody, switching up who plays it goes a long way. Instrumental timbre provides one of the simplest but most powerful joys of music. The best dance records of the period display an impressive degree of variety using “just” the tune by changing orchestration, rhythmic accompaniment, and instrumental texture between and even within strains.

Other arrangers leveraged these ideas while taking greater thematic liberties. Some soloists developed the song into brand new melodies while expanding on the harmonic possibilities of the underlying chords. Yet the best “commercial” arrangers choreographed instruments while keeping the tune front and center. Nathan Glantz’s rendition of “By the Light of the Stars” is a great example.

Recording for Edison as the “Tennessee Happy Boys,” Glantz and his band stay close to Arthur Sizemore, George Little, and Larry Shay’s Tin Pan Alley piece. They lodge it firmly in listeners’ heads. Publisher Jerome H. Remick might have thought this was simply a band doing its job, but I’ve also had the sound of Glantz and his band playing the song stuck in my head for years:

On the first chorus, the tenor saxophone plays the lead softly in long, lyrical lines that would fit in a hotel ballroom. The trumpet syncopates the lead on top without losing the tune. Playing the unadulterated melody as a foundation, the trumpeter can take greater liberties without “mutilating” the tune. It’s a simultaneous straight and hot treatment.

At the bridge, the alto sax bends and elongates the melody with jazzy licks but never discards it. The trombone and ensemble split the verse, trombone laying down the melody right on the beat and answered by raggy trumpet. The sax section pares the next chorus down to clipped accents over a shuffling accompaniment; the song is still there, just more by implication than full recapitulation. The trombone adds a gruff surface to the bridge, the alto sax is more lyrical on the verse, and the soprano sax’s bright, gooey color almost parodies the chorus. Yet it’s still easy to hum along with each segment. The tune is now familiar enough for the tenor sax to answer the ensemble’s stop-time reduction with looser hot phrases. By the end of the record, all melodic fetters are off, and the trumpet plays even hotter over cymbal backbeats.

The record balances composition and arrangement, the composer’s codified work and the musicians’ contributions, theme and variation. It’s a hot record, but for a listener looking for clear melody and a steady beat, it splits the difference and maybe opens their ears to other possibilities.

Discographer and musician (as well as generous and knowledgeable expert) Javier Soria Laso says this is a stock arrangement, perhaps doctored by members of the group. If the shifts in instrumentation and subtle melodic/rhythmic alterations were part of the published orchestration, that just reveals a subtle hand at work. Every stock arrangement has an arranger behind it, and even the straightest of straight melody statements still needs a musician to play it.

The Art of Compromise

In jazz (as it’s commonly discussed today), the term “soloist” is often reserved for a musician extemporizing on the harmonic material of the song. Among historians and fans of early jazz, “hot solo” usually implies the melody was just a catalyst for the soloist’s ideas.

So-called commercial musicians didn’t have either option. Yet that didn’t necessarily preclude creativity. Some thrived on the subtlest melodic paraphrase: crafting slight rhythmic and melodic alterations—hesitation, anticipation, elongation, ornamentation, articulation, doubled notes, timbral variation, etc.—to play with a song even as they kept playing the song.

The best hands turned even a “straight lead” into a personal statement. The trumpet’s opening chorus on “Chloe” with Sam Lanin (d.b.a The Gotham Troubadours for Okeh) offers a master class in pinpoint inflection, embellishments, and slight rhythmic adjustment:

If a recording even allowed room for getting hot, it was definitely not on the first chorus of a new song. Yet even composer and publisher Charles N. Daniels (a.k.a Neil Moret) might have appreciated the way this trumpeter delivers his work. It’s clothed in a warm, smooth, harmon-muted sound. Ornaments and rhythm add momentum to the melodic line while keeping things singable. Syncopations on the second eight bars of the chorus sync with the brighter harmonies before a descending run complements the sax section’s ascending run when they take over.

Of course, the idea that “it’s the singer (not the song)” isn’t unique to any form of music. Jazz, in particular, always had an affinity for it, going back to New Orleanians’ “ragging” a tune. There are countless examples of what Gunther Schuller, after Andre Hodeir, described as “a type of improvisation based primarily on embellishment or ornamentation of the melodic line.” Composer, instrumentalist, and music historian Allen Lowe explains how musicians ranging from James Europe’s syncopated orchestras to Earl Fuller’s defiantly chaotic take on the Original Dixieland Jazz Band “used phrasing and rhythmic variation as a means of pre-jazz invention before moving to the next step, which was to restructure melody as contained and related to the accompanying harmony.”

Maybe the trumpeter on “Chloe” was literally improvising (i.e., doing things on the spot), but it’s a different concept than what Lowe and Schuller describe. The proportion of musician-to-song feels different. The song isn’t source material; it’s the song. The song and the musician are not equals. The musician’s ideas are not the (main) point, yet there they are. If ears could squint, we’d “see” this trumpeter. It’s like virtuosic self-effacement.

The Threshold for Individualism

This example is from a record that might be described as “commercial music” of the period. It’s telling that Brian Rust’s jazz discography doesn’t include it. With his idiosyncratic distinctions between “jazz,” “dance music with obvious jazz flavoring,” “dance bands” playing all varieties of music, and other categories, Rust might have heard “Chloe” as “straight dance music,” something that “does not deviate as much as a quaver from what is written in the score.”

This trumpeter had to sell that tune. Their knack for melodic paraphrase might be so subtle as to seem inconsequential. Still, it’s unlikely they were reading those inflections, embellishments, and slight rhythmic adjustments off the page. It begs the question of how much variation is needed to qualify as “improvised, original, creative, etc.” If you are coloring within the lines, you can still pick the colors. The lines might even inspire you.

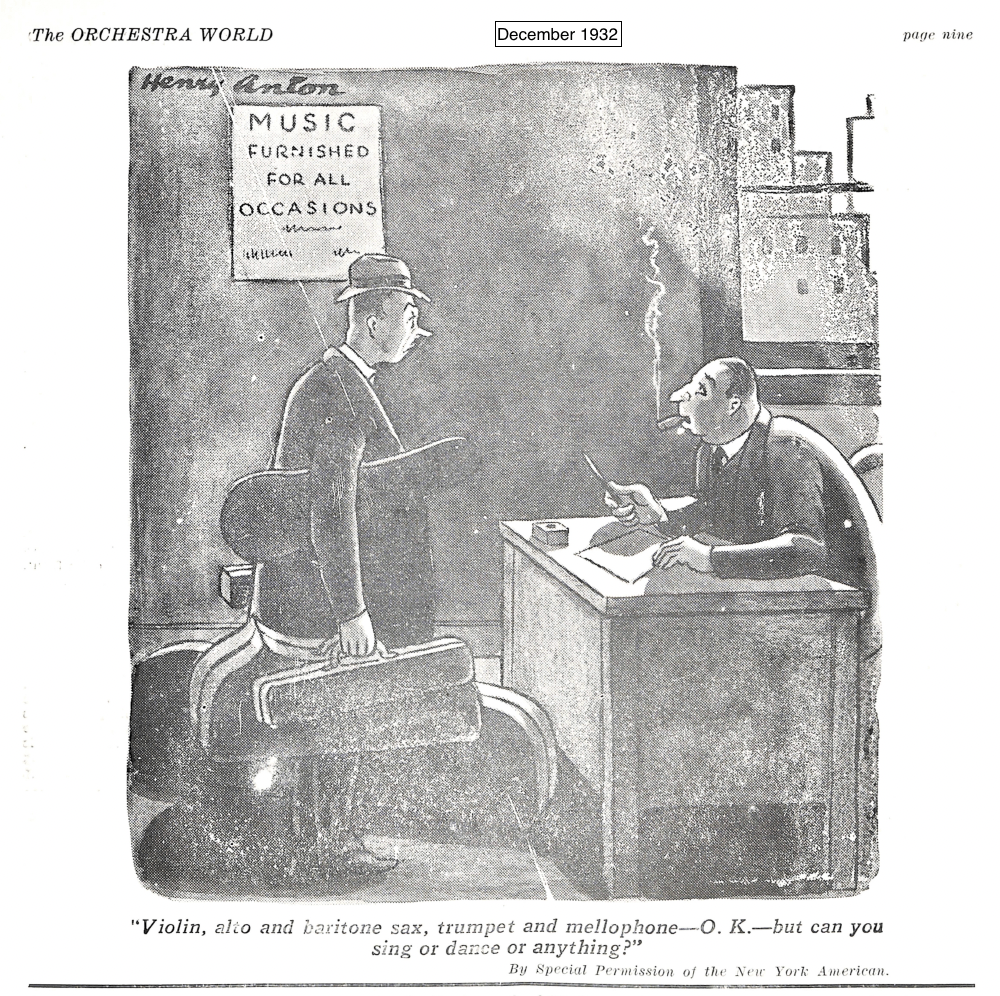

As for the demands placed upon these musicians, they might feel like a limitation or even a violation. To some players at the time, it was just part of a job. Others would recollect how much these convictions chafed at them. Later musicians and listeners might even assume that liking—or even preferring—this sort of thing is objectively unhip.

Musicians tamping down their creativity for the sake of commercial interests and a supposedly unadventurous audience is one of the oldest and saddest tales in the book. But for at least a few, it may have been a unique challenge or simply a different means of expression:

In some of our sweet arrangements in Tommy Dorsey’s orchestra, we get a chance to express our feelings, and when we carry the melody, we just sing it out as if we actually were vocalizing. It also means that you have to feel your music, too…

—Hymie Shertzer, “Tells Technique of the ‘Singing Tone,” Metronome, April 1940

If it wasn’t jazz, it wasn’t always a compromise. Some people even liked it.

Thanks so much to Colin Hancock for sharing his thoughtful ideas on this subject!