Leo Reisman is probably best known among jazz aficionados for featuring Bubber Miley both live and on his Victor recordings. An important collaborator with Duke Ellington and influential trumpet stylist, Miley had to play behind a screen with the white bandleader-violinist on live dates. Nearly a century later, Reisman usually comes up in discussions about disgusting racial politics or as the bandleader who happened to be there for Miley’s searing outbursts, like those of “Puttin’ on the Ritz”:

As for the rest of Reisman’s music—hundreds of records and some film appearances across an active musical career spanning decades—he more often played sophisticated dance music in commercial settings. Record collectors sometimes note that while Reisman could get hot on record during the twenties, he later segued into (relatively) sedate, lushly arranged music. For at least one commentator, this meant “abandoning the jazzy hot dance arrangements of the 1920s and turning to more banal, traditional ballroom sweetness.”

Some of Reisman’s music may have been labeled “jazz” during the twenties. A century later, there are important cultural and critical distinctions between jazz by the likes of Ellington and Louis Armstrong versus jazz-influenced popular artifacts once deemed “jazz,” not to mention music well outside the tradition by Reisman and others. In fact, most historical discussions of popular music don’t mention Reisman. Yet a contemporary profile allows some insight into his music (as opposed to its social context or the leader’s popular appeal and financial success).

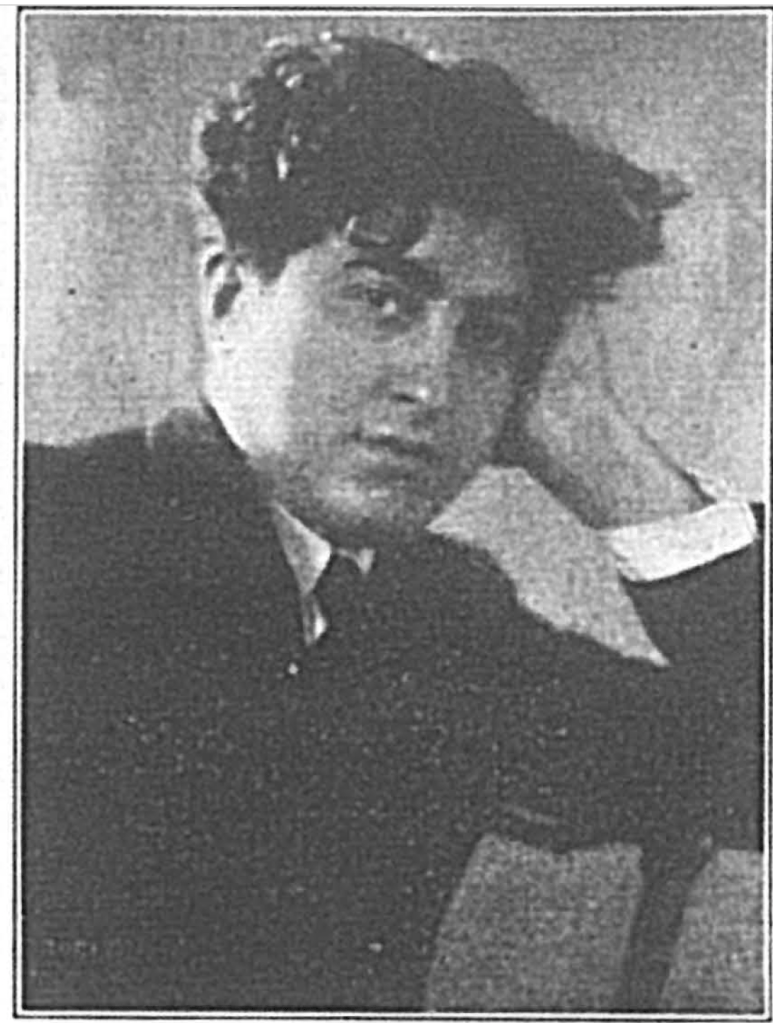

In an article for Jacobs’ Band Monthly of November 1925, George Allaire Fisher singles out Leo Reisman as “the most successful, artistically [emphasis mine], of the many popular orchestras that are now so busily engaged in this broad land of ours in churning up sound waves.” The caption to the accompanying image of Reisman—posed like a pensive intellectual and determined artist with tumbling hair, head resting on an outstretched palm, and a reflective but calm stare into the camera—says that he “demonstrated the broad difference between ‘just [emphasis mine] jazz’ and ‘modern American music’ artistically presented.” Fisher also praises Reisman for “dance music played so that it was at the same time as musically interesting and as intriguing [as] a dance rhythm.”

The praise rests on some elitist assumptions. There’s unfair (but common for the time) minimization of jazz. There’s also the implication that musical interest and danceability are two separate but unequal criteria. Fisher doesn’t disregard dancing; he even quotes the respected classical pianist Mischa Levitzki declaring Reisman’s work as “the best dance music [he] ever danced to.” Composer Darius Milhaud shared this opinion. But Fisher positions musical interest—pure formal listening—over dancing. There’s real deal musical appreciation, and then there’s this enjoyable activity that doesn’t get music in some absolute sense. Even Fisher’s choice of sources seems intentional. The implication is that dancing is fun, but these authorities from the world of European art music know art when they hear it.

This elitism feels ironic given Fisher’s elevation of popular music to an aesthetic object. He offers critical admiration for an orchestra playing popular tunes for dancers and shows. He’s not just profiling a band that rakes in cash and fans. He’s analyzing what makes their work musically worthwhile. For example, he describes the band’s “beauty of tone color… variety…symmetrical precision, melodic beauty…proportion…balance in instruments and arrangements.” Beyond having a good beat, Fisher unpacks what he hears under all the tapping feet:

While maintaining a steady rhythm, Reisman secures the effects even of rubatos and accelerandos by the way in which instruments are balanced against each other and by the subtlest sort of syncopation. He moreover uses every possible effect of tone color, shading, melodic variation, and dynamics so that there is a continuous but always pleasing variety … He also plans the rhythm and dynamics so that the music has a lift between the strong beats rather than a thud on each strong beat … the effect of the music is to carry them along …

Fisher’s use of technical terms, discussion of dynamics and other musical details, and his attention to the level of thoughtfulness in this music probably surprised many readers. This was popular music (as opposed to “serious music”). The suggestion that popular music could be serious probably confused some readers. It likely confused Fisher’s colleagues at Jacobs’ Band Monthly. Several of them thought that only conservatories and concert halls offered music worth considering as music. They certainly said so in their columns.

The Leo Reisman

The rejection of American popular music at the time included what many called “jazz,” whether it meant Louis Armstrong, Ted Lewis, or Leo Reisman. Jazz has now mostly shed its associations with popular music. We hear it in conservatories and concert halls. We read musicological analysis of Armstrong’s music once reserved for the likes of Bach. Reisman played symphonic, through-composed dance music that is largely forgotten in historical discussions. The suggestion that he could be “better than jazz” might now seem preposterous.

At the time of Fisher’s profile, Reisman and his band were playing at the Hotel Brunswick in Reisman’s hometown of Boston. The 28-year-old violinist was already an industry veteran. He began plugging songs in a music store by age 12, attended the New England Conservatory, and briefly worked in Baltimore as a symphony musician and salon orchestra leader before coming home to continue leading dance bands. By 1929, he was playing fancy spots in New York City while recording for Columbia and broadcasting over WBZ.

Reisman was also a cultural pioneer. In addition to hiring Miley, Reisman featured Johnny Dunn in his “Programme [sic] of Rhythm” concert at Boston’s Symphony Hall on February 19, 1928. Some audience members walked out to protest a Black musician playing onstage with the band. But critic and dancer Roger Pryor Dodge remembered Dunn playing “East St. Louis Toodle-Oo” as the only highlight of hearing Reisman, who otherwise only played “the most discouraging trash…the same attempt to use [jazz] without respecting it.”

Reisman was not a jazz musician. Improvisation, the blues, and the unique rhythms of jazz were not his priorities. Yet he was a musician with his own musical priorities alongside his business motives. He outlined these priorities and advised dance band leaders and musicians throughout a series of columns for Jacobs’ Band Monthly. Reisman had ideas about dance music. It was not just a way to make a living or get his name on the marquee.

Plenty of listeners stop Reisman’s recording of “What is This Thing Called Love?” right after Miley’s full chorus paraphrase solo. Some wait until after the vocal to hear his obbligato behind the vocalist. They’re there for the jazz. The “sweet” stuff is too often dismissed as commercial filler that jazz artists had to endure.

Miley gets plenty of space on “What is This Thing Called Love?” But the ensemble work reminds us that the “filler” was the livelihood and craft of musicians like Reisman:

After the vocal, soft strings, with maybe a flute in the mix, create a thicker texture and slightly louder dynamics. Up to this point, the surface texture has been light: just trumpet and vocal with a few light violin tremolos and a prominent bass. The strings prepare the way for the full ensemble. The verse can sometimes seem like an afterthought, so introducing both the full band and the verse in one sweep makes an impact. It also introduces a purely symphonic effect, contrasting with the jazz solo and sweet vocal with jazz accompaniment. The subtone clarinet adds more atmospheric contrast; we start with hot lyricism and end with whispering introspection.

The whole thing is so well choreographed in its exploitation of texture and scale. The carpet of strings, dramatic crescendos, and ballroom-friendly atmosphere may not work for everyone. But they do work on their terms.

Ironically, a romantic title like “Twilight, the Stars, and You” shows us the hotter side of the Reisman band and a possible peek into what Fisher heard around this time:

This might be what Dodge meant by “use [of jazz] without respecting it.” There’s a solid beat for dancing. It doesn’t have the same elasticity and accent of jazz, but it’s far from sleepy. There are saxophones, the quintessential jazz instrument of the Jazz Age, but they’re playing smooth, legato melody over pumping bass with crisp brass syncopations. The sax and violin duet doesn’t try to be jazz. Instead, it spins ballroom melodic deconstruction: the sax keeps the tune available to the listener the whole time while the violin takes it apart.

There’s some hot trumpet followed by violin and woodwinds, cooling things down. The trumpet returns, muted and soft, right before a rhythmic ensemble. A clarinet obbligato injects more jazz flavor, but things end on a chiming piano coda. The arrangement lets the musicians and dancing listeners have their hot and get their sweet, too.

On the other hand, “Just a Gigolo” may be what collectors who lament Reisman’s later work had in mind. It’s as sweet and symphonic as it gets—but not banal:

A muted trumpet hints at the melody over descending winds, starting the record on a curiously suspended feel for a dance record. A brighter, clarinet-led sound finishes the intro before the first chorus with strings. It’s tempting to dismiss this as sentimental, generic, or dated. Still, the violins’ slurred articulation makes the melody sound like it’s intoned through a resonator. Things become popular for a reason.

When the brass takes over the next chorus, they’re backed by reedy saxes (perhaps led by the tenor). Brass over saxes is nothing innovative per se, but the sections are not in dialogue like on a Fletcher Henderson chart. They’re massed for a voluminous effect that makes this already expanded band sound even bigger and richer. A symphonic-style transition leads to the verse, where those brawny saxes take the lead with lower brass adding further depth. And we’re only halfway through the record.

The level of attention devoted to cutting a three-minute record is inspiring. Critics may describe this music as “over-arranged,” which begs the question of whether music can ever be over-improvised. Of course, it all depends on the music.

Music That’s Also Popular

No one would expect a jazz documentary to include Reisman. Most of his repertoire did not sound anything like jazz as it’s commonly understood today. Jazz purists sometimes reject his music for that reason. Unsurprisingly, jazz musicians of the time (just like today) were less doctrinaire. Some were just earning paychecks. But interviews and diaries show that many musicians enjoyed playing in different musical environments.

Reading some later coverage, it can seem like this was music exclusively for brainwashed consumers shuffling background music at social events. But the attentive dancers who appreciated the sounds on top of a steady beat; the listeners, seated and dancing, who savored the musical details; the musicians who enjoyed the music (and the steady gig): they all heard something.

Especially in the pre-rock era, jazz had a significant impact on American popular music, and many musicians moved freely between the two worlds. These interactions between jazz and popular music may earn the latter a passing mention in jazz histories. But for some jazz historians and writers, these are compromises (not exchanges). They hear jazz influences in popular music as “close-but-no-cigar” imitations or shameless appropriation.

You can find examples of subpar music in any genre, and there are plenty of people ready to dissect them, but analysis of the best work may be swept aside. That includes many dance bands; big bands (as opposed to “swing” or “jazz big bands”); studio orchestras; and even so much well-orchestrated, sincerely performed music filed under “Easy Listening” by the local download conglomerate. The best examples of twentieth-century instrumental popular music often land in historical limbo. They’re not jazz, and they’re no longer popular, but they are music. What can we listen for now?